Kerry Yo Nakagawa—who founded the Nisei Baseball Research Project (NBRP) to uncover, share, and preserve the stories of early Japanese Americans playing baseball and their impact on communities—discussed several critical points explored in his study of baseball’s role in Japanese American history during his visit to “Chatter Up!” on April 3, including the game’s ability to connect groups separated by language and cultural barriers. You can also read a recap of this discussion here, or check out the full conversation on our YouTube channel.

Shane:

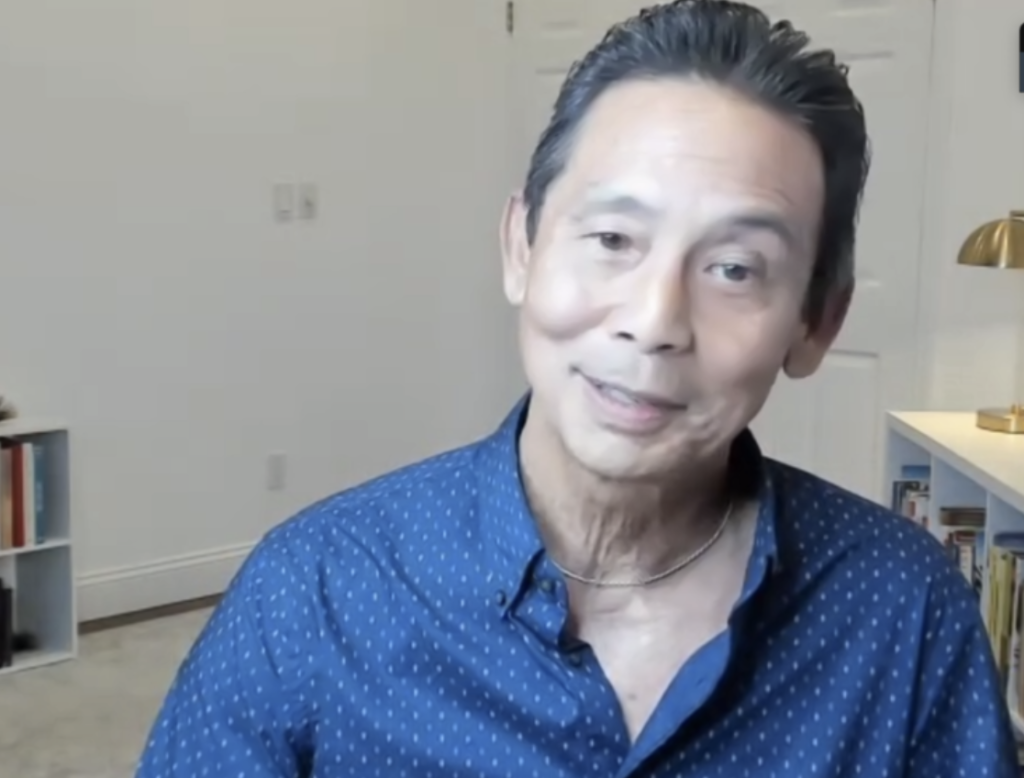

Even though we’re all getting to know you already, I do want to give a formal introduction to everyone, in case they’re not aware of your background, so I’m going to do that real quick, and then we’ll get into some Q & A. So for those of you who are not aware of Kerry Yo Nakagawa’s background, he is a Japanese American baseball multimedia extraordinaire. He’s an author, filmmaker, historian, storyteller, athlete, promoter, educator… We could probably throw a couple more in there. About 25 years ago, while coaching his son’s Little League team in Fresno, California, Kerry was inspired to embark on an exploration for future generations: the legacy and culture of Japanese American baseball that runs through his veins, and his whole family legacy. That inspiration evolved into the nonprofit Nisei Baseball Research Project. The NBRP’s mission is to preserve the history of Japanese American baseball, and bring awareness and education about the Japanese American internment camps through the prism of baseball. With this mission in mind, Kerry curated the “Diamonds in the Rough” international exhibit that traveled to places like the [National] Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame in Tokyo, and in conjunction with that exhibit, [he] directed the documentary “Diamonds in the Rough” alongside his God-Papa, Noriyuki “Pat” Morita, who people know for his famous roles in The Karate Kid and a bunch of other films too. Kerry’s written two books: “Through a Diamond: 100 years of Japanese American Baseball,” and also “Japanese American Baseball in California.” He’s published a couple books by Bill Staples Jr., who’s on the call here and is a former “Chatter Up!” guest. He co-produced curriculum guides for Stanford University, and through a long labor of love, produced the movie “American Pastime,” which is an independent film that won the audience favorite in San Francisco, and is a great film, that I just watched this week for the first time, that focuses on baseball in the internment camps. So through all these efforts, Kerry has earned a reputation as an expert in Japanese American baseball and the Japanese internment camps. He’s been asked to do things like be a consultant for the Hall of Fame’s “Baseball as America ” exhibit, he won the Tony Salin Memorial Award from the Baseball Reliquary. A litany of accomplishments, and for all those reasons, and many more, we’re very happy to have you on with us Kerry, so thank you, and it’s good to see you. I’m really glad that I’ve gotten to know you recently.

Kerry:

Thank you, Shane. It’s an honor to be in everyone’s presence. You know, I’ve watched so many JapanBall YouTubes with your past guests that you have [had]. I just feel very honored to be part of this amazing team and your mission and your crusade, because it’s such an important dynamic that we recognize these not only Japanese American baseball players, but the players from Japan, that are raising the bar at a major league level, and I think that’s one of the things that the NBRP is trying to crusade and lobby for, the godfathers, the Issei and Nisei ballplayers, that today’s players are standing on their shoulders. So many of our pre-war players had the passion, they had the heart, and the ability to play Major League Baseball, but they just never got an opportunity, much like the Negro Leagues and the Latin leagues. So we’re very hopeful that at one point we can have the Baseball Hall of Fame [and] Major League Baseball recognize our Issei and Nisei pioneers, as our American ambassadors to the game pre-war, as early as 1918. I’m very proud to be part of this amazing group, and thank you for having me.

Shane:

You’re welcome. I know that your organization and what you represent is in alignment with a lot of the values that we have: the global aspect of baseball, the unifying aspects of baseball. Yuriko [Gamo Romer] and Bill [Staples Jr.] both highly recommended I get in touch with you as soon as I got to know them, so here we are today. I wanted to kick things off just talking a little bit about that “Aha!” moment when you’re coaching Kale’s Little League team; what led up to that moment, and where did you get started?

Kerry:

Well, Brandon Zenimura and Kale, they were little 10-year-old All-Stars back in the day. I remember we’re in a small farm town called Kingsburg- Michael [Westbay] will probably remember it, it’s close to Hanford- we watched these little leaguers win their championships, and I saw the back of their jerseys, and I took this picture and it said: “Nakagawa” and “Zenimura.” I thought, “My gosh, that’s been four generations since my Uncle Johnny and Kenichi Zenimura and the Fresno Athletic Club made tours to Japan as early as 1924, and then back again in 1927, and then they were back in 1937.” And so I thought, “Wouldn’t that be such a tragedy if these two ancestors of their great families’ dynamic, and having that DNA of baseball in our families for so long, not surface?” And so I went back home, and that was kind of the epiphany moment. I told my wife, I said, “I’ve got to do something; a documentary to record this amazing history on Kenichi Zenimura and what he did,” as a player, a coach, a manager; how he broke down barriers in the ‘30s, coaching two all-white Twilight League teams in an era where Japanese Americans were discriminated a lot against, yet here was Zeni, coaching “Al’s Bar” and “James and Company,” a body shop vendor company, because in in Fresno, we had a “Twilight League” where major leaguers on the offseason, semi-pro players would play, and it was the hotbed for baseball in Fresno, we have two Hall-of-Famers from our town: Frank Chance and Tom Seaver, of course, and so many other major leaguers that came to our Central Valley. So that kind of moment, I went back to my wife- I was producing and directing at an ABC affiliate in Fresno at the time- and I said, “I have to do this documentary- otherwise, it’s gonna get lost.” And so I said, “Would you be alright with just one income?” She agreed, and so I left ABC and tried to do this documentary. It always seems like synergy- I think coincidence is too vague, I liken it to synergy, or synchronicity- [but] all the doors closed for a documentary, but at the same time, we found out the Fresno Art Museum was doing an exhibit on Japanese culture and history. So I approached them with the idea of having a small exhibit on Japanese American baseball, and they said, “Well, baseball really isn’t part of this cultural month.” I said, “Well, if I can bring you some photos, I think I could convince you otherwise. It’s definitely been a part of our culture.” So I went in the next day and took these photos, and the curator of the Fresno Art Museum says, “Hey Kerr! I didn’t know that your brother-in-law was Ken [Ewan]! We went to kindergarten together! Let me show you the museum spaces, and tell me what area you would like.” And so we got this one square footage area about the size of a Little League dugout. On the first day, after we put the artifacts and images together, we had 1,000 people come to the opening. And one of the people involved with the opening was Rosalyn Tonai, at the National Japanese American Historical Society, and after it, she asked if we can maybe bring up the exhibit to San Francisco. So we did, and on the first day of the exhibit in San Francisco, CNN’s Rusty Dornan covered it, and it was running every hour on the hour on their coverage. I remember Rusty saying, “When you see an exhibit like this on Japanese American baseball history… I never knew that. You look at the legacy of Japanese Americans, you think it starts post-war, but I see all these pre-war images, and how great these ballplayers were throughout the country. From the Tijuana Nippons down south, to the Vancouver Asahi in Canada, to the Hawaiian Islands West and as far east as Nebraska Niseians.” So she says that this is an amazing story, and when she came and told us that, then I knew that this was much bigger than just a few families that played baseball, and so we’re lucky enough to travel out throughout many of the states, and then ended up in the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and a year later, we’re at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Tokyo, which was incredible.

Shane:

Wow. Really, it’s so cool that you just had this little inspiration, and all of a sudden you’re at multiple Halls of Fame.

Kerry:

Well then it opened up a lot of other doors, because then once we had the exhibit going, I thought, “Well, my forte is multimedia,” and I thought, “We have to have a documentary that goes with the exhibit.” So I recruited our God-Papa, Noriyuki “Pat” Morita, to help me write the doc. He was our on-camera host, he was our narrator; in our book, he wrote the foreword on the docket. He did so much on camera with our film, he pitched it to Senator Daniel Inouye, Wally Yonamine, got tremendous community support behind it to get our film made. With every aspect of NBRP, Pat was in on it; he wanted to be part and to support it. In introductions, when we were together, he would always introduce me as his godson, and I would call him Dr. Mo, and he would call me Yo-man. And although we’re not God-kids or parents through blood, through that love of all these shared projects is how we connected, and then it went from the documentary to our book: “Through a Diamond: 100 years of Japanese American Baseball.” We were honored to have Tom Seaver write the foreword, Pat wrote the introduction. With the curriculums, Pat wrote the letter to the teachers and to the students, and then for the film, he was supposed to play the gambler and the moonshine maker, and just a couple months before we started shooting, Pat passed away, unfortunately. But in spirit, the “Nori” character is in his tribute, as well as the credits at the end honoring Pat and Desmond Nakano’s (our director’s) father.

Shane:

Speaking of Pat, I know he sang the national anthem before lots of games at a lot of cathedrals of baseball, but the coolest one was the story that you shared with me about your old high school. Can you share that story with everyone about his anthem?

Kerry:

Well, real quickly: in 2001, we took our documentary to the Palm Springs International Film Festival, and we were finalists. “Beautiful America” from Germany won the title, but just the fact that we were finalists was quite an honor. Pat wanted to know- he was in Las Vegas at the time- he said “You call me, Yo-man, let me know how we did.” So I said, “Well, Pat, we were finalists, but I’m gonna take our film to my old high school and show the entire high school the documentary,” and he said “keep me posted on that.” So I remember going to the high school, and the whole gym was ready for a pep rally. And I thought, “Oh my gosh, these kids are ready for a pep rally, not for documentary.” And yet, when we started the movie, you could hear a pin drop; they were so attentive. At the end, Pat sings the National Anthem, of course, and the entire freshmen, sophomore, junior, and senior [classes] all stood up while he was singing the national anthem, and they put their hands to their heart. Especially after 9/11, that was the most patriotic act that I had ever felt and witnessed at that moment, and I was so proud that this happened at my [alma mater,] the school I went to, and how proud I was of this young audience that were so engaged and so respectful, and especially at the end, so patriotic, and I’ll never forget, during the Q & A- which I savor, to hear these questions. One of the students says, “Mr. Morita and his family were incarcerated during World War Two. Why does he like singing the national anthem with the San Francisco Giants and the Los Angeles Dodgers and the Arizona Diamondbacks and the Sacramento Kings, wherever he goes?” My pride is I can answer pretty much everything I’ve ever been asked, and I couldn’t answer this question. I said, “I’m gonna call him tonight. I really can’t answer why he likes to sing the national anthem; I know he sings it with a blues riff and he sings it well, but deep down, I really don’t know why he likes to sing it, but I’ll get back to you and your principal and let you know.” So I called Pat up that night, and I told him the amazing response we got and this young kid’s question. He goes, “Yo-man, you tell that kid or the principal that I’ve been around the world four different times, with The Karate Kid and in so many other projects, and in my 40 years of being a celebrity, this is the greatest country in the world, because I wouldn’t want to live anywhere else. The reason why I sing the national anthem, despite what happened to our families, our communities, this is still is the greatest country in the world, and that’s why I sing it.” And so I was able to get back to the principal, and it was a pretty moving answer and a pretty amazing question from this kid from my hometown.

Shane:

Wow, that’s awesome. So I would I do want to talk a little bit about the current conversation at hand, with the Asian American movement, to raise more awareness to the anti-Asian hate and discrimination. Obviously, your work has been going on for multiple decades now, and you’ve always felt it has always been important, but can you talk about how it resonates today? How the [idea] of preserving the message, and telling the story of internment camps, is important to tell 50, 60 years later?

Kerry:

Well, I remember especially after 9/11, see[ing] the scrutiny and xenophobia on a lot of my friends that were Armenian American, Sikh American, Muslim American, and in a small farm town, a Sikh American business owner was shot and killed by some uneducated person that took it out on him, because he thought that he was somehow responsible for 9/11. I always would say in my presentations then, and I say it now, that instead of learning from our past mistakes in history, we seem to keep repeating them. The names change, but the xenophobia continues on. During the Olympics in China, I remember, my daughter was going to UC Berkeley, and she was saying a lot of the Asians, and especially Chinese Americans, were somehow being singled out because of the tension between China and the U.S. at that point. So now, here we are in 2021. I’ve always crusaded and felt that we should embrace the immigrant experience [with] every immigrant that comes to the United States, I mean, we’re all immigrants other than Native Americans. We all immigrated here, whether we’re Italian American, Irish American, Latinos, Blacks, Asians, and we should embrace the beauty of each cultures’ food, their art, their music, their traditions. For us to be here at this point in time in 2021, and seeing so much racial tension that with all other Americans- I don’t like to use the word minority, I think all of us are the other Americans- it really pains me to see that history really hasn’t changed; only the names have. I’m hopeful that our grandbabies that are coming up, are going to be in a world that is going to be more progressive and embracing to each other’s humanity, which I feel that we all are connected, whether the color of our skin is different, or our faiths are different, we are all are connected by humanity. One prime example of that is when I took Pat and Howard Zenimura back to Gila River. Our exhibit was at the Phoenix Museum, and we were able to take them back to their old homes on the sacred grounds at the Pima Indians. I remember Governor Mary Thomas, who [was] the spiritual leader of the Pima Indians, sat us down in the tribal Pima Indian tribal chambers, and she asked us, “Why did you pick today to come to Gila River?” And so Pat said very shy-like, “Well Governor Thomas, Kerry’s exhibit was at the Phoenix Hall of Fame museum, and we wanted to come back to our old home, because we haven’t been back here for 56 years.” She goes, “Wow, I was a little girl when these camps were here, and my parents never let me get by the barbed wire. But we knew that your babies in your community were being born on our sacred land, and your elders were dying on our sacred land. And we just wanted to say today, on behalf of the Pima Indians, how sorry we were that this happened to your community members on our sacred land.” And Pat interrupted her, “Well, Governor Thomas please- don’t apologize because the government forced us onto your sacred land, you had no choice.” And she goes, “Well, no, Pat. For all these years, the Pima Indians have felt that if we would have told the government, ‘No, you can’t put Japanese Americans on our sacred land,’ then it might not have happened.” I never saw a connection between Japanese Americans and Pima Indians, but at that moment, there was this amazing realization for me personally, that we all are connected. It doesn’t matter whether we’re Pima Indians or we’re Japanese Americans, or whatever color of our skin is, or what nationality we belong to. It was a beautiful moment that she brought to us. But you and I, all of us know here, that if it wasn’t the Pima Indian reservation, Japanese Americans would have been put on another Indian Reservation down the road. But to see that sincerity and that amazing humanity that she shared with us, I really realized then- and even to this day- the spirit of Mary Thomas I hope can permeate everywhere, and at some point, everyone can realize that we need to come together as a country, as peoples, and really be more progressive and embrace this amazing immigrant experience.

Shane:

That’s powerful stuff, that’s amazing. Yuriko has her hand raised, I’m gonna go to her.

Yuriko:

Hey, Kerry, how are you? Hi, Shane. I’m pretty sure that the first Japanese Americans brought baseball back to the United States from Japan, and then, pretty quickly it seems like, they connected their various communities through baseball, and I think it came to life in the camps when that happened. So can you talk a little bit about why you think Japanese people and Japanese Americans were so drawn to baseball, and what created that lovely community connection that also resurfaced, even when they were all behind barbed wire in the camp?

Kerry:

Sure, Yuriko. When I did our research, I was amazed to find incredible authors around the story in Japan, and to see how deep… I mean, when we think about baseball and in the United States, [it’s around] 1839. But when you go into Japan, as early as 1872, baseball was even in Japanese curriculum, on woodblock prints; they were studying the game in classrooms. So this love of the game that the Issei had as kids, when they finally came over- like our family, when my grandfather came from Hiroshima, Japan to the Big Island, Ola, worked in a sugarcane plantation, and then his dream was to come to the mainland. So in 1886, he was one of the early Issei to come over- They already had this love for the game, because they had studied it in schools, they had played it on their playgrounds. And I think like Takeo Suo said, “To put on a baseball uniform was really like putting on the American flag.” But I think it really went deeper than that. I think they wanted to prove how great they were in baseball, even though they might not understand or communicate with the other ethnic groups. They certainly knew all the universal language of inside the lines and how to play the game; outside of the lines, after the game, it got a lot blurrier. But for them, I feel they wanted to prove they were the best immigrant teams, and they knew how to play baseball; they wanted to prove they were the best, and I think they were ready and willing to get into Major League Baseball, and then World War Two happens. So here is a situation where some potential great Nisei ballplayers had a chance to maybe even become a major leader before Jackie Robinson in 1947, but because of World War Two, their careers were stopped. I think of Henry Honda, who signed a contract with the Cleveland Indians on December 3, and then on December 7, the bombing of Pearl Harbor nullifies his contract; they tear it up. So many great ballplayers that we had pre-war, and even during World War Two: Henry Honda from the San Jose Asahi was given a shot to pitch, and he threw his arm out in camp, and yet the Dodgers that at the end of the war gave him a tryout, but his arm was still never the same. So I really think about how these wonderful, great ballplayers, and the Issei that came over and had this love at the game already for their children, and once their kids were born here, they supported them even more, through fundraisers to raise money for their equipment, or to stash bills into their pockets as they’re rounding the bases because they hit the Sayonara home run in the camps, or whatever it took to support [them]. This was a way for the Issei to express themselves verbally, mind body and soul, to put everything behind their kids playing the game. We have so many photos of them in the camps wearing ties and the women in their Sunday best, all the way around the field just to watch the games, so the incredible passion and the love for the game really carried over for them. But I think it really goes back deep to when they were studying it in Japan; even before they came over to the islands or to the mainland, they had this tremendous love of the game and respect for the game. I think that’s why the Nisei picked it up, and of course it just keeps on going, one torch after another, one generation after another, we continue on. I hope that answered your question.

Yuriko:

Just want to hear your stories, that’s all. But one thing is, there’s something about it, it’s a community building sport. So I think it’s like really cool that there’s still a pretty big network of sports amongst the Japanese American community, which I think back then was a little more baseball, maybe a little less basketball than it is today.

Kerry:

Well, because baseball was the early game that they only knew of; basketball, football really came a lot later, and of course golf, tennis and a lot of other sports, but baseball was the game for the immigrant experience, I feel, especially at the turn of the century, when everybody’s heroes were playing. I think it was a time where baseball was the game- there [weren’t] alternatives like we have today. So kids today have so many options to play so many different sports, but at the time, baseball, I think, was the way to have fellowship on road trips. Many of the ballplayers met their future romances and wives, or relationships and their outreach to the other communities that weren’t Japanese American. To see just so many aspects of the game, and how it’s spread throughout all over, as I mentioned, from Tijuana, to Canada, to the Hawaiian Islands, to all the way to Nebraska. So what a dynamic it was for the early immigrant experience.

Shane:

I love that quote about the American flag, not because baseball is an American game, but just because it’s like by putting on the uniform, you’re putting on this cloak entering a new country that automatically makes you relatable, and automatically gives you a way of reaching out and kind of finding common ground. I imagine immigrants of other countries, who didn’t have 50, 60 years of baseball behind them, it was harder to find something in common, whether it was food or music or whatever it might be, but really quick, the Japanese were able to integrate themselves through baseball.

Kerry:

As an example, Shane, my dad was born in 1905 in Caruthers, California, in the Central Valley. My grandfather had a 20-acre grape farm, and my uncle Johnny, who later became like the Nisei Babe Ruth, made these tours to Japan as early as 1924, ‘27. My grandpa sent my dad to Japan for education, but he came back as a young teenager, and he was kind of like a Kibei generation, considered like almost a generation of no country, because he really wasn’t accepted in Japan because he was foreign-born, and then when he came back as a teenager to the Central Valley, he had an accent, which he held until he was 88 years old. But he immediately broke down barriers by being such a great football player, sumo wrestler, and he threw a nine inning no-hitter- because back in the pre-war days, the high schools played nine innings, not seven like today- against Leyton High School. So he gained immediate respect, and I think through the sports arena, no matter what sport it is, no matter what color your skin is, if you can excel at a high level and keep raising that bar as an amateur, as a professional, you will gain immediate respect. I think that was what my father actually expressed to me. I think that was kind of the badge of honor for all Americans. Maybe outside the lines of sports, the discrimination, a lot of the xenophobia of the times, would actually go away if you could prove you’re as good or better than anybody else in any sport. I think that was kind of the touchstone to allow our ballplayers to gain the respect, to show their skills, to show their passion and to bring pride to their communities.

Shane:

Totally. I want to talk a little bit about the “American Pastime” film, just because I don’t know a whole lot about filmmaking, but being an independent film, shot on location in a desert… it’s a proper, well-made film with a full cast. By the way, John Kruk was a well-casted character in there. I’m just curious about the origins of that, and then what it was like getting that off the ground, and then the feeling of when you finally were releasing it in festivals and getting such a good reception.

Kerry:

Well, I got a call from- later he would become the producing partner- from Barry Rosenbush, and he was working for 10 years trying to do a film about the incarceration, but nothing kind of clicked for him. He heard me on the World Radio program, and I was talking about just these incredible ballplayers pre-war wise. In particular, I mentioned this ballplayer that had pitched for Oregon State, and then him and his sister, Kay Kiyokawa, they grew up in Hood River, Oregon and their parents had Fuji apples. He was a great pre-war pitcher, war comes, and he gets, because of the generosity of the Quakers, friends of society, they sponsored 500 Nisei to go to colleges, but you’d have to go to UConn- University of Connecticut, Ohio State, or University of Delaware. So Kay and his sister picked the University of Connecticut. I said to Kay- and we’re on our way, by the way, to the Japan Hall of Fame to be honoring, again, these Nisei pioneers, and Kay and I sat next to each other on the plane- I asked them what was it like to be in a so-called enemy alien playing for UConn as the starting pitcher, and he was the starting running back for their football team. Kay Kiyokawa was like four-foot-10, a little taller than a fire hydrant. And he said, “Well, we were playing the University of Maine, and as I left the on-deck circle, all the stands on both sides started chanting, ‘Tojo, Tojo, Tojo, Tojo, Tojo.’”

Editor’s note: “Tojo” refers to Japanese Prime Minister Hideki Tojo, who presided over Japan during World War II. The chant was a racist taunt, generalizing Kiyokama to the man considered to be a public enemy of the United States at this time.

I said, “Wow, how’d that make you feel?” He goes, “It pissed me off.” I said, “So what did you do?” He goes, “I hit a double to right field, and then in my second at-bat, I come out of the on deck circle, and only the University of Maine students were chanting, ‘Tojo, Tojo, Tojo, Tojo, Tojo.’” I said, Well, how’d that make you feel again?” He goes, “It pissed me off even more, so I hit a triple to right-center. But what was incredible, Kerry, [was] when I came up for my third at-bat, I left the on deck circle, both stands started chanting ‘slugger, slugger, slugger.’ And we laughed.” I thought about that on the plane, and I use that in a lot of my presentations, because I think that’s the goal of our NBRP, and thank goodness we have an internet wizard like Bill Staples that is in constant connections with our NBRP and one of our board members, but it shows you how we want to keep breaking down barriers and changing perceptions, much like Kay Kiyokawa did with three at bats. I think that story resonated with Barry, and he contacted me and said, “I’d like to come to Fresno and see the layout of the land, and I have this idea.” I’ve been in the film business since 1980, and I was wondering, “Well, here’s a Hollywood producer, and where’s this gonna go?” Sure enough, he came down, was very sincere and we connected, and we felt that to get a Japanese American director and writer would be essential. So we contacted Desmond Nakano, Desmond contacted his producer friends Tom Gorai and David Skinner, and instead of just one battery to two batteries, now we had five that were all very passionate about this project. So it took five years, but with the help of Wally Yonamine writing letters and Pat Morita going to Washington DC and trying to pitch Senator Daniel Inouye on it, we were able to get funding, but it came ironically by Tom and Barry going to Japan and presenting the president of Fuji TV the cover of my book- on the cover it’s my uncle Johnny, Kenichi Zenimura, the Nisei ballplayers, and Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. Mr. Hasagawa looked at the book and said, “This reminds me of my relatives that were treated so harshly in the United States during World War Two. Does this movie have anything to do with that?” And they said, “Oh, absolutely, it does.” And he goes “Then I will do everything possible to help you get the money to make this movie,” which he did. He got TNC to basically help fund the film. Five years later, we had 65 cast and crew members working in that 120 degree heat in the Utah desert, pretty close to the original Topaz camp. I remember in the mornings, the mosquitoes would be biting us, in the evenings, they would come back, but we had insect repellent, we had water. Even though we were an hour away every day from Salt Lake making this trek to our set, I think when we saw John [Iwata], a former MIS soldier in a full wool suit, hat and overcoat, and he had a suitcase where he put the oxygen tubes into his nose. One searing hot day, I asked John to take a break, get into shape, and I remember his response was “No Kerry. My parents were here at Topaz. If they could take four years of this, then I could take one day.” I’ll never forget the bonding of our cast and crew when we heard John’s statement like that, because we knew they didn’t have insect repellent, they didn’t have cold water like us, they couldn’t go back to a hotel. To see the passion of this one former MIS soldier wanting to really help out on this film, much like in his parents’ spirit, it really forced us to try and tell the best story about the incarceration through the prism of the internees, and the veterans of the 442. And our uncle, John T. Suzuki, was actually Senator Inouye’s radio man in Company E, when they saved the lost battalion in the French Vosges mountains. We wanted to really honor the spirit of these young teenagers that volunteered out of these camps to fight for our country, and then went on to be the most decorated in the history of World War Two, as what they call them, the Purple Hearts Regimental Combat Team. So that was the combination of all these different dynamics kind of coming together through synergy, through synchronicity, and through the spirit of all our internees and veterans that wanted to show and kind of humanize it, because it’s not written in history books, this was our way to tell the story, and to get it out there in a cinematic way to entertain, to educate and hopefully inspire.

Shane:

Wow, well done, I must say, well done.

Joseph:

Hi Kerry! Thanks for taking some questions, this is really great. So I have a deep interest in this idea of baseball as a major connecting point between people, something that has this particular unique ability to sort of break down barriers, and really key in on what you said, that we all really are kind of one in the same. So, I’m curious to know if that’s something that you have explored beyond the US-Japan connection, and if you have any stories in regard to that, and also just generally, if you can pinpoint what you think it is about baseball that creates that connection, that sort of lets us leave everything else outside of the lines, and break the barriers down when the game starts.

Kerry:

Well Joseph, I think about my first time in Cooperstown, and it was a breakfast in this little town at this inn that was built in the 1880s. And here was Buck O’Neil, Sharon Robinson, Roberto Clemente, Jr. and myself. We were talking about just what you talked about. Roberto Clemente, Jr, talking about his dad and how it impacted baseball and Latinos. Of course, Sharon Robinson’s dad was Jackie, and the legendary Buck O’Neil talked about the Negro Leagues. He got all excited because I told him about our uncle Johnny was in Japan in 1927, and it was a 2-2 game and it was against the Philadelphia Royal Giants, and my uncle was in centerfield, and Biz Mackey hits a towering a ball to left center, and my uncle went over the wall, three rows into the stands to try and bring it down- of course he didn’t, but the picture that we have, the news took, is him climbing down the wall as Biz Mackey is circling third base. It was a great moment for both teams that were undefeated at the time. I remember the conversation came about that exact question: what is it about baseball and Latinos, baseball and Blacks, baseball and Asians, baseball in America, and Major League Baseball that unites us. I think it comes down to just that love of holding that ball, the father [and] son playing catch together like the Kinsellas did in “Field of Dreams,” whether it’s mother-daughter, father-son, father-daughter, mother-son, that’s something that we all treasure. We had our heroes that go beyond their faith and the color of their skin. I think [that] we as ballplayers, we know that once you hit that big field, you’ve got to have the five tools; you’ve got to have the speed, you can hit for power and for average, you’ve got a strong arm, whatever it takes, and I think it doesn’t matter. Look at Major League Baseball today, how internationalized it is. But what that key moment is for everyone, I think it’s whether that touchstone to that ball and those seams and the legacy within your own family and relationship with the game and your parents, your dad, your grandfather might have had with it, and sharing the stories, passing the torch I think other than any other sport- and of course, baseball is in my DNA, so I’m partial- I think that’s going to be the lasting legacy and a touchstone to every family’s legacy, to have that love of the game for the baseball or football or golf or tennis or whatever you have. I think it is once you can prove that you can play the game at a high level, you get that immediate respect, you are able to share the stories once your career ends. As I would tell my son, “Hey, play it for as long as you can, because once it ends, then all you have is memories. So make those memories great. Make those relationships great, because the memories always stay with you and those relationships.” To this day, I still have great friends I treasure. Bill Staples invited me to a fantasy baseball camp in 2006, and I got to play. Our coaches were Frank Robinson and Brooks Robinson, and we made it to the World Series, and in the only time I ever pitched in my life, Bill went five-for-five and had five RBIs. I remember every inning, I’d look up at the sky and point to my dad and my uncle, because I knew they were with me in spirit, because I wasn’t a pitcher, I was a shortstop, but they were and I just felt their presence.

Joseph:

Great listening to you talk. Those are great stories. Thanks for sharing that.

Michael:

I just have something to add to the whole community thing. Back in 1995, right after getting married and bringing my wife over here to Japan to join me, we moved into the community that I still live in now, and one of the things that we had was community baseball, I saw in the Kaidon– which is the kind of circular that goes around the neighborhood- that first sports day that year, they were opening up tryouts in baseball for the community team. I went out and I got to know so many people in the community. I’m this foreigner, with a foreigner wife, in this new community that I’ve never been to, and it was baseball that really brought me into the community, not only, as you say, between the lines, but also outside of the lines. It was through my associations with the people in the community with baseball, that I learned about the Chonaikai – the community center and what they offered, and all of the different events that are going on there. The baseball team sponsors a mochi pounding event every winter. The Japanese friends of mine at work- it’s mainly a Japanese company- they were amazed that I knew my neighbors, because even the Japanese here are not getting to know the people next door. I think a lot of their wives do, but they don’t, and so baseball is really a community builder. It’s the baseball team that also happened to be the leaders of the Chonaikai, the leaders of the community. And so, I think that what you’ve said with baseball building a community, is ingrained here in Japan, especially because it is the community leaders who are going out there every weekend and just playing some baseball for a couple of hours.

Shane:

That’s awesome. Thanks for sharing that. Michael. [Kerry,] you mentioned Buck O’Neil and Sharon Robinson. Can you talk a little bit about what NBRP did with them and like some educational activities? Through Bill Staples and Coop Daley, who’s on the call, we’ve learned a lot about the connections between the Negro Leagues and the Japanese players. So can you talk a little bit about that, Kerry?

Kerry:

Well, Buck O’Neil, especially after we saw Ken Burns’ “Baseball,” he was already a hero of mine and the fact that I got to know that he was going to be speaking through “Baseball as America” and I was going to be able to chat up about the Japanese American baseball experience. I remember my wife and I- it was one o’clock in the morning in Cooperstown, and the fire alarm went off in the town. They said that Buck was going to be a little late from the airport, and so we weren’t gonna get to meet him that evening, because there was a special dinner for the speakers, and I told my wife, I said, “Wow, Buck O’Neil is so famous that they put on the fire alarm when he came into town.” Well, the next morning when we finally met at breakfast, it was a real fire; it wasn’t for Buck. But to see him bigger than life, and forever ageless at 94- he got all excited when I mentioned Frank Duncan, that my uncle Johnny had played against them and the Nisei, he goes “My manager was Frank Duncan!” And so we talked about the 1935 NBC baseball tournament that was held in Bismarck, North Dakota, and he said that he remembered Satchel [Paige], his good buddy, was pitching for the North Dakota Bismarck team that made it to the championship, and the Nisei team were one game away; they lost to the House of David, otherwise they would have faced Satchel. He goes, “I watched those Nisei ballplayers- they were hitting and running, bunting and running, double stealing, playing small ball but they kept advancing. They had a picture that reminded me of Satchel, and it gave me chicken skin;” my grandpa in Hawaii would call it chicken skin, not goosebumps. But I knew that Buck was talking about Harry “Tar” Shiraichi, who had seven different release points, much like Satchel did- he didn’t name his pitches, but I knew he was talking about the same guy, so I mentioned that to Buck. Buck, we spoke a number of different times for Baseball in America’s traveling exhibit in Oakland and L.A. and Cooperstown. Just so many different times, I had an opportunity to have lunch and dinner with Buck and travel to the airport, and he was so knowledgeable on the game. What an ambassador for the game, never carried any bitterness in his heart. The book that he wrote was “I Was Born Right on Time,” because most of the media would ask him, “Don’t you wish you could have played in the major leagues instead of just the Negro Leagues? You had so many great ballplayers.” And he goes, “Well, hey, I played with a lot of the best ballplayers in the world, and they weren’t in the major leagues; they were in the Negro Leagues.” I always remember his amazing spirit: forever young, and never carrying any bitterness, always so encouraging and positive. And not only that, all the contributions that he gave to the sport and to all of us as fans of Buck O’Neil. Of course, Sharon [Robinson], with her dad and how incredible she was… in fact, she even wrote a letter to the teachers and students in our curriculum that we developed through Stanford University. Also Shane, if there’s any teachers or students that would like our electric curriculums on incarceration, we offer it for free, and I could offer it through JapanBall or through our NBRP website or on Facebook- we’re the Nisei Baseball Research Project; thank goodness Bill Staples is such a wizard with our website there. So if there’s any teachers that would like to learn more about baseball behind barbed wire, we certainly offer these curriculums for free, and to have Buck and Sharon and Pat all involved with it, in their subtle ways, was amazing. So yeah, Buck O’Neil and Sharon, I could go on for hours talking about those stories, but I know we’re limited by time but I was just very honored, like I am today, to be in their presence, and to hear their stories, and share some of ours.

Shane:

People love to debate about players that should be in the Hall of Fame. I think if there’s one guy that should be in the Baseball Hall of Fame that’s not there now, it’s Buck O’Neil. He’s such a great ambassador for baseball and accomplished [so much] on the field, and as a coach too.

Kerry:

Well, I called Buck- I remember in Kansas City, when we were all anticipating him getting in with the 17 other Negro League ballplayers, and when Buck’s name wasn’t on that list, it crushed me, and I called him. I’ll never forget, as Buck O’Neil would say at the end of the conversation, it was, “Doc-” he never calls you by your name, he’d always call you doc- “the Hall of Fame has to do what the Hall of Fame has to do- you just keep loving Buck O’Neil.” I said “I certainly will Buck.” I remember sharing stories at the airport with him- because Bill Staples and the internet, he’s found box scores, where we had out of 12 box scores, Nisei All-Stars versus Negro League All-Stars, the Nisei they won a majority of the games. And now that the statistics are coming out through Major League Baseball and the Negro Leagues, Buck was like, “I can understand that,” and Buck even wrote a nice blurb for our book.

Yuriko:

Actually, this is not a question, I had to throw this in there: every couple of years, the Hall of Fame has a special award, the Buck O’Neil award at the Hall of Fame. This is the year that you can make nominations, and Lefty O’Doul’s cousin, Tom O’Doul, is campaigning hard, and there’s a lot of people that would love to see Lefty O’Doul get that Buck O’Neil award. Most of it is about his ambassadorship as the Japan-US baseball ambassador, and so the one catch is that you have to write a letter and send it into the Hall of Fame, but if anyone here is willing to write a letter, because it would be lovely to get Lefty in- he has a plaque on the Japan Baseball Hall of Fame. So Buck O’Neil is honored in a very special way for the whole thing.

Shane:

Is that like a letter writing campaign where a bunch of people write, or are you saying one person writes it on behalf of the candidate?

Yuriko:

The idea is that you have to write in a letter saying that you would love to see Lefty O’Doul get this award, but it has to be written- you can’t send an email you have to send it as a letter recommending.

Shane:

So everyone on this call could write a letter?

Yuriko:

Yes, in fact, there’s a whole letter writing campaign for Lefty O’Doul for the Buck O’Neil. I think if you probably go to one of my Facebook pages, it’s on there but there’s definitely all this stuff, and Tom has been trying to do this for years, so I’m trying to spread the word.

Kerry:

That’s a great idea Yuriko, thank you for mentioning that, because Tom is a friend and I remember when Lefty O’Doul got inducted into the Baseball Reliquary, which was kind of our West Coast Hall of Fame. I personally feel that Lefty should be in on just statistics, not just a Buck O’Neil award, I think he should be in the Hall of Fame for all his performances as a pitcher, as a hitter. Real quick Lefty O’Doul story: Tom O’Doul, we were honoring Lefty when he got inducted into Japan Hall of Fame, and as a filmmaker, I wanted to do a small documentary to you know honor that tribute at the Lefty O’Doul’s restaurant in San Francisco. So I went out to Daly City where Lefty’s buried, and there were tons of cemeteries, and I was late, and it was about ready to rain. At this one place, I finally stopped that, said, “Yeah, Lefty’s here; here’s the map, because we get a lot of requests.” So I went storming around, and the sprinklers came on, and I couldn’t find it on the map, and I was having to leave. I remember kind of the sun broke out a little bit, and there was one tombstone in the distance [that] I could see with a little bat on it. I screamed to the universe, “Lefty, is that you?” So I went over to the gravestone, and sure enough- the man in the green suit. “He was here at a good time, and he had a great time while he was here,” with the .361 lifetime batting average circled on that bat. I was able to lay a few flowers down, film that small portion that I wanted at his gravestone, and that was important because that was the last shot that we had in the documentary. We had some of his former players: Con Dempsey, Dino Restelli, that went on the ‘49 tour to Japan with Lefty O’Doul. Cappy Harada was there, and the three of them hadn’t seen each other for 70 years. Cappy was serving under General Marquardt and General Douglas MacArthur, and MacArthur said, “How do we change all this negativity and these dark clouds that we have in post-war Japan as they’re rebuilding?” And Cappy, the captain, said, “Can we bring my friend Lefty O’Doul and the San Francisco Seals for a tour here?” And he goes, “Well, what are you waiting for?” So he called Lefty, they had a 10-game exhibition, they had over half a million people come to the game. Cappy arranged in a night game at Koshien Stadium, to have the American flag and the Japanese flag raised at the same time. One of the generals saw that and he said, “Who allowed both flags to go up at the same time, it should have only been the United States flag!” And they said, “Cappy Harada.” He goes, “Get him over here, I’m gonna get him court martialed.” So Cappy went to him, and he says, “I understand that you allowed both flags to go up. You’re going to be court martialed, then I’m going to tell General MacArthur.” And he goes, “Well, I already asked General MacArthur, and he said it was okay.” But I think there was a quote by General MacArthur, saying afterwards, “That exhibition tour was the most diplomatic act during that occupation that they could ever imagine.” Sure enough, when the Seals left, a lot of that negativity went away. The love for baseball, and the Seals coming to help heal those wounds of war, made a huge difference. So I agree, Lefty should be in the Hall of Fame- I think by his merits alone, but if he has to be in through the Buck O’Neil award, so be it. That’ll be a huge honor as well.

Shane:

Well, Yuriko will have to rally the troops for that letter writing campaign, and we’ll have some homework then. Thanks for the offer about the curriculum- I know we have a couple teachers on the call, so any of those teachers, let us know if you want that curriculum.

Ted:

I would love to have that curriculum. I’ve been retired for 20 years, and I taught social history, seventh and eighth grade. I’ll tell you, one of the things I showed them was the incarceration of the Japanese, to tell them what happened, that we put Japanese Americans in concentration camps. I was pretty radical in those days, and I’m glad I was. I had to show them what happened. We need to teach history that way, we need to learn by our historical mistakes, like you said, and we haven’t. We haven’t yet. Even the way our country teaches these other countries of the world- you look at Vietnam. We’ve just got to learn by these mistakes, we have to learn! I get very emotional about this. One time I taught American history, but instead of when the country was founded, I taught it from the 1970s on backwards. I got away with doing it, because they didn’t know what they needed to know.

Yumi:

Hi. It’s not a question. I’m very, very happy to hear your stories, because I was born and raised in Japan- mostly educated in Japan, I went to college here. My knowledge of Japanese Americans was probably one or two lines in a history book: “After the Pearl Harbor attack, the Japanese Americans were put in camp;” that was probably like one or two lines in our history. I lived in Seattle for about two and a half years the first time that I moved here, and I met Japanese Americans, but at that time, I did not know the history about what the Japanese Americans went through, and lately, I’m learning more about it. I live in New York City, so it’s really hard to meet Japanese Americans, but when you mentioned Cooperstown, that was probably a striking time that I saw these glorious players. I stood in front of the pictures of Japanese Americans, and it says, “Even in the Japanese camps, they played baseball, and because they were from a different state, you don’t have a uniform, so they’re wearing the uniforms like Ohio, or Arizona, that was a tee-[shirt].” And it just struck me that time, like “Oh, my God, I really need to know more about Japanese Americans.” When I visited L.A. last year, for the first time, I visited the Japanese American Museum. I’ve seen the movies, but I don’t have any family members that I’ve met, because I live on the East Coast- it’s really hard to meet Japanese Americans, just hearing my friend’s parents’ or grandparents’ stories. So I’m learning, and I think baseball is one of the things that’s going to be the tool to teach people, for the younger generation… even like my generation, I’m a little embarrassed… not to show discrimination against race or anything like that, but you’re talking about the baseball kind of like show the races or experiences, I think [for] a greater audience of Americans and Japanese, [who] will accept hearing those stories, and incorporate with discriminations. I really feel like, for the first time, I’m crying to listen to this Zoom call, because it’s so emotional what you have been through, I can only imagine. I haven’t had a chance to visit the campsite, but after COVID is kind of calmed down, I’m planning to visit some places, so whenever I have a chance, I’d like to [see the] Japanese Americans, and the baseball that they played, especially [since] I have connection with some of the Japanese community, so telling them about the history, and how that history is probably going to deepen the meaning of how they’re playing baseball, and I think it may make changes for some of them. I just wanted to thank you, and I’m very ashamed that I haven’t seen your film, but I’m going to see it pretty soon, and really, thank you. I really appreciate your talk today.

Kerry:

I appreciate your comments. You know, just hearing your comments I think about Cooperstown and the Baseball [as] America exhibit. Two poignant artifacts was the Hank Aaron hate letter, during the city tours of all the Major League Baseball cities, that was a very significant letter. When Hank Aaron was breaking Babe Ruth’s record, that letter of hate of him breaking Ruth’s record, was in our exhibit. And then, our wooden home plate that we got from the Gila River, Arizona, Pima Indian community, was also another very significant and engaging artifact. For this day today, as an update, that original home plate, through the generosity of the Arizona JCL, is now at Cooperstown under the umbrella of the “Era of Change,” they call it. All the artifacts in this small exhibit were very significant in changing baseball somehow. Even though we would crusade, and we’re lobbying at NBRP to get Major League Baseball to recognize our pre-war American ambassadors that created this bridge across the Pacific, for great players like [Masanori] Murakami-san, [Hideo] Nomo-san, Ichiro [Suzuki]-san, [Hideki] Matsui-san, [Daisuke] Matsuzaka-san, to raise the major league bar even higher. To think about our great players that we had that were considered too small for Major League Baseball, but nobody says that about Jose Altuve or Dustin Pedroia, even though they’re small players, but they become MVPs in Major League Baseball. We’re hoping that much like the pride and the passion for the Negro Leagues that is permanent at Cooperstown, much like the All-American girls that’s permanent, Latinos in Baseball, we’re hoping that Japanese Americans and Japanese Nationals that played baseball here, will be recognized with a permanent exhibit, not just one wooden home plate. I know that on the timeline, “Baseball During World War Two,” Japanese Americans were very significant during that era, because America imprisoned their own Americans only because of their race at that time. So we’re hoping through the prism of baseball, to have these touchstones, artifacts of history of our legacy and players, so that we can educate more people on every coast and around the world, and to let them know that our Issei a Nisei ballplayers, many of the players today in Major League Baseball, they’re standing on the shoulders of those early Issei and Nisei that risked and crusaded and had so much great travel on ships to go to Japan, to Korea, to Manchuria. China, just to be ambassadors for our game. So thank you for your comments, and I hope at some point, you can go to Cooperstown and we’ll have an exhibit on a more expensive scale, so we appreciate your comments.

Yumi:

And if you’re going to do any campaign, I will really help it get the signatures and make it happen. Today, my friend who’s in this group- she’s half Japanese and American and she had a really busy week, and she’s asleep, but I will let her know- she’s really connected [with the] Japanese community here in New York City, and we will help to get signatures and make it happen.

Kerry:

I appreciate it. Thank you so much.

Jenny:

So first of all, I want to apologize, I got the times wrong, because I’m in Tokyo, so I joined a little bit late, so I missed some of this, so if you addressed this early on, I apologize. I teach a course on international baseball, and I’ve been doing it for about a year now, and as it’s been going on, my own personal interest is sort of relating the social issues and how baseball is a reflection of a country’s culture, its ills and its goods elements. We do an extensive focus on the Negro Leagues, and how that’s a reflection of racism towards Black Americans in American culture, how we can see these microcosms, and the Japanese American situation during the war, after the war, and all of these things… I want to figure out a way to incorporate this in. So I will definitely be in touch about your curriculum. But for me, I want to find a way to connect it to Japanese students in a way that it really resonates with them. When I talk about issues of discrimination or racism, they often say, “Well, there isn’t any in Japan, we’re a homogenous country.” One in 10 marriages in this country is now an international marriage, so that’s not true, and I don’t think they realize it. So what would you recommend? Or how would you suggest framing these experiences of Nisei Americans, or the experience of the Japanese American baseball in a way that you think would resonate with Japanese students, who are internationally minded, but maybe don’t have this frame of reference, because they’ve maybe not experienced it? They’ve not been the ethnic minority, those sorts of things in their current framework. What would you recommend to help connect it to them?

Kerry:

I think that’s an amazing question- I think of, in our film “American Pastime,” Clint Eastwood, at the time, did a film called “Letters from Iwo Jima,” and on our DVD extra, you’ll see the trailer of “Letters from Iwo Jima” on our film, and on Clint Eastwood’s movie, he has a trailer for “American Pastime,” because he felt that it was the two audiences would support both films. But I remember Clint- which we were honored [to have] an amazing filmmaker like him to appreciate our film- he was disappointed when they took the movie to Japan, most of the youth in Japan had no knowledge about the Iwo Jima battle, because it’s so many generations or decades removed. So I would say to them that- which is a tough question coming from a Japanese American perspective- is that they probably don’t know a lot about what happened during Pearl Harbor, the bombing, and probably don’t even know what happened to Japanese Americans as a result of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Through our curriculum, we have different activities that they can go through that, I think internationally, it would work not with the US students, but it would work with your students too, because it will give them a foundation, kind of a touchstone to our history, what happened to our families because of the result of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and then they will back it up saying, “Oh, well, we didn’t realize that, you know, the Issei from Japan that came to the United States were so passionate about the game; we didn’t know that it was part of our curriculum, baseball, even though started in the US,” and now we’re hearing stories that it started in Egypt. To see these kids now kind of rehash the history of World War Two, and then how it affected their grandparents, their Obāchans and their Ojīchans, but then again, how did it affect Japanese Americans in the United States, and their timeline of having to deal with four years of living in the desert wastelands and six months in a animal horse stall at the County Fairgrounds, and then coming back, after four years, to absolute hatred and hostility, because they were still considered enemy aliens, and to see that- 98% of Japanese Americans lost their homes, their businesses, their college education, so they had to kind of start from ground zero. The Issei were too old, really, to rebuild, and the average age of a Nisei was only 24. So I think once they hear that history, they would be a little bit more sensitive to, internationally, how it fits in today’s world and how we all are, as I mentioned, kind of connected through the story of humanity, and through this dynamic of baseball, no matter what faith we belong to, no matter what color of our skin is, and we have the passion, the tools and the opportunity to take it to another level, inside the lines or even outside the lines, and once I think they learned that history, I think they would have a different perspective.

Jenny:

Oh, that’s an interesting point, thank you. And I think that, statistically, the average age of Nisei was 24. I’m teaching third and fourth year university students, so that they could probably resonate- imagine everything getting ripped away from you right now, and having to start over.

Kerry:

Exactly. Imagine them taking their civil liberties, their constitutional rights away, their dignity, all the different dynamics about it. They can personalize with putting all their most valuable possessions in two suitcases, and go live in an animal stall in a county fairground for six months. And yes, they can wash out all the manure with fire hoses, but most of the county fairgrounds, in the extreme heat, it didn’t matter- that smell and that future aroma was going to resonate. I really feel for the elders- my grandmother had a restaurant, my grandfather had a general store across the street, in the 30s, and when they had to leave for a four-day train ride to Arkansas, my mom, who was just a teenager, through the blinders peeking through the bottom, could see the racist with sign saying, “Get out of Fresno, never come back to California.” She was concerned about what was going to happen to them on this four-day train ride to Arkansas. My grandmother, being a very progressive and proud business owner, an Issei woman, says, “this is the greatest country in the world. All immigrants have to pay a price. We’ll go to these camps, prove how loyal we are, and then we’ll come back.” And unfortunately, my grandmother contracted cancer and she died six months later. In our culture, we cremate our loved ones, but they didn’t have a crematory in Jerome, Arkansas- they sent her body to Hattiesburg, Mississippi, and two months later, in a Folgers coffee can, my mother got her mother’s ashes. There was a piece of paper on her ashes, and she thought it was her name, but all that said was “Jap woman,” when she opened it up. So the inhumanities didn’t even stop with my grandmother’s death, they just labeled her as woman, but that’s the tragedy. The inspiration is, when they came back three and a half years later, at a train station were the McClurgs and the Ravens, my grandfather’s neighbors on this 20-acre great farm that had been spit at and egged because they were friends to our family, caravaned them back to our 20-acre grape ranch, gave my grandfather a cigar box, and when he opened it up, there was no cigars in it; it was full of cash. The McClurgs and the Ravens not only took care of our ranch for three and a half years, they gave them back the profits. That’s a 1% story, and we’re so grateful for the Raven family, which we consider a part of our family, and the McClurgs, because they saw through the xenophobia and the prejudice and discrimination; they just saw great friends and neighbors, and they took care of us. There’s 120,000 stories, these are the two Nakagawa ones I like to share- the tragedy and the inspiration. Maybe that’ll resonate with your students as well.

Jenny:

Yeah, I certainly hope so. I think for me, like when I talk about baseball with them, living in Japan for 16 years, baseball is my “in” into Japanese culture, it’s how I feel [like] a part of the Japanese community, and so I share that with them. I think that showing them how sports, or all these things, can build connections and remind you of the humanity. When we draw artificial borders just for the sake of passports or pandemic protections, there are real world human consequences. Thank you very much for your answer. I appreciate it.

Craig:

This has been by far the most moving one of these I have been on, and the most memorable. Just amazing. I’m probably learning more about the internment camps on this call than I knew before. The one other place I had learned a little bit about was the film “Allegiance;” do you have any input on that, or were involved in any way?

Kerry:

Well, George Takei contacted me because they wanted some ideas. There’s a small scene where the characters wear a baseball uniform, and they act out on stage a little bit about being part of a team in the camp, so they wanted to confirm the color scheme. This was when “Allegiance” was just in San Diego before it went to Broadway in New York, and so I was very proud to just share a little bit about our Issei and Nisei baseball history pre-war, so that they could capture the right colors for the uniforms in the play, and I got to see it- not live- but I did see it at a theater, and I was glad that, George Takei was- as well as all the other actors- gave great performances.

Craig:

I see the previous questioner just mentioned that it’s actually being performed in Tokyo right now. Thank you for doing this, and thank you for educating us so well… not just us, but everyone, but us in particular; this was fascinating.

Shane:

Thanks, Craig. That was a perfect last participation there, because you summed it up well. I agree, I think this is such an important conversation to have, and I learned a lot. Hopefully everyone on this call learned something. I’m just really glad we got to hear from you. It’s not our typical baseball conversation, but for that I’m grateful; it’s good to mix it up a little bit and talk about these topics that we had today. So Kerry, thanks so much for joining us, and like I said, I’m so glad that Bill and Yuriko put us in touch and recommended [you], and I couldn’t have asked for anything more.

Kerry:

As I always say, Shane, that’s baseball when you cook it up. It’s such a connective energy to our different generations. Like I mentioned before, just to be part of this to “play catch” with all of you, I’m honored to be in your presence, and honored to share my stories as a storyteller; that’s what we all are as filmmakers. We always felt that baseball would be immediate, it would grab women, men, it’s genderless. But like an onion, baseball, we can keep unraveling it like an onion skin, and get into more deeper levels besides baseball itself. So that’s the thing that I’m very appreciative today, that we started with JapanBall and baseball, but like an onion, we kept unraveling to see a lot more social and deeper issues that baseball can bring out, and it can inspire, and it can educate, and entertain at the same time. So on behalf of all our board members, Bill Staples, NBRP, and all the Issei and Nisei ballplayers that never got their recognition, or do, we really appreciate that you guys are in support of our crusades and lobbying efforts in the future, with Major League Baseball and the [National] Baseball Hall of Fame and the [Japanese] Baseball Hall of Fame in Tokyo as well. So thank you all for being here, and have a great Easter weekend and a blessed weekend, and, again, Shane, thank you so much for your time and effort and energy to have me on.

Shane:

You’re welcome. Thank you, we’ll be in touch. We’d be happy to support whatever that NBRP is doing. So thank you. You’re welcome to sign off, and anyone else is too. I’ll stick around for a few minutes if anyone wants to chat, but we ran a little bit late, so you’re welcome to sign off, and thank you for joining us. I appreciate it, everyone.

Ted:

Thank you very much.