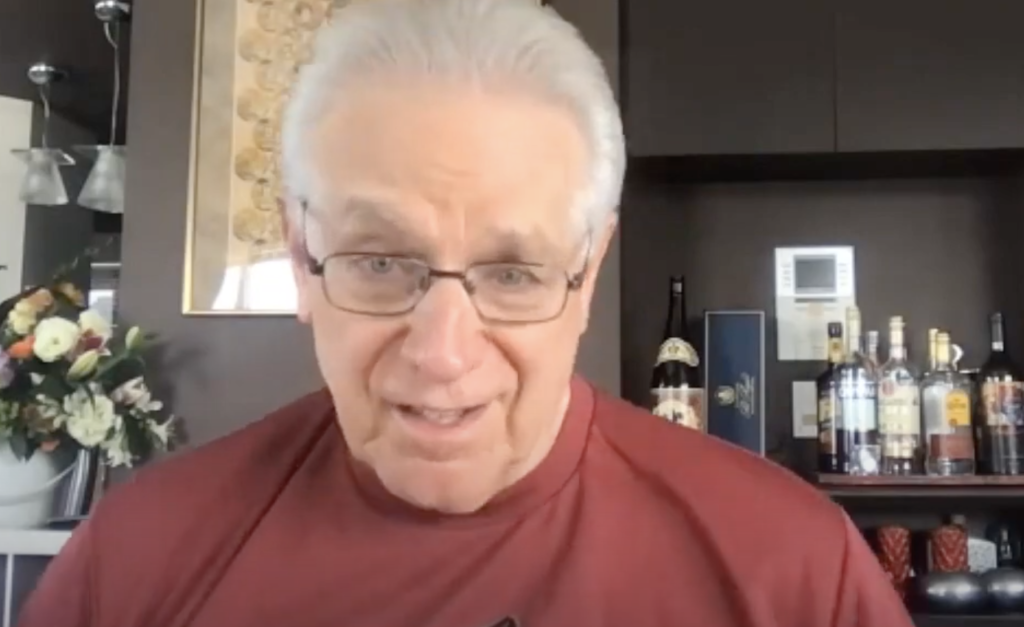

There is perhaps no one who knows the game of Japanese Baseball better than anyone other than Marty Kuehnert, the first foreign-born GM in the history of Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB). Kuehnert, who served as the first general manager of the Tohoku Rakuten Golden Eagles, joined JapanBall’s “Chatter Up!” on June 4 to discuss his experience with the team, and the challenges he faced trying to build it from the ground up. Check out the recap of this discussion here, and be sure to watch the full video on our YouTube channel.

Shane:

All right. I’m gonna introduce Marty, our special guest and the reason why we’re all here. I’ll do a quick rundown of Marty’s background for everyone, and then I’ll ask a couple questions, and if anyone has questions, I’d like to encourage as much participation as possible from our audience. Alright Marty, I’ll put you in the spotlight so everyone can see you. Hello. Thanks again for joining us. This is Episode 22 of “Chatter Up!” and I don’t know how it took so long to get you on, but I’m so glad that you’re here.

Marty:

Happy to be here.

Shane:

All right. So Marty Kuehnert was born and raised in Los Angeles, California. He earned admission to Stanford University, where he was a catcher on the baseball team, but perhaps more importantly, while he was there he participated in a Japanese exchange program, which set the course for quite an interesting story in life in his adopted home country. I think [his] first break was that he met legendary baseball ambassador Cappy Harada, who asked him to run the Lodi Orions of the California League. He ran the Orions as the GM – it was the first ever Japanese-owned sports team in America – and then he won the Executive of the Year Award the next year, so a nice start to his career there. Then he returned to Japan, [and] was in charge of Sales and Promotions for the Taiheiyo Club Lions, who are now the Seibu Lions. That’s where things really started to take off, it seems, from different various aspects in Japan and baseball and sports for Marty. Fast forward, he’s written seven books, hosted a weekly TV show, written various long-running columns – which I think a lot of us have read – worked extensively as a TV anchor and commentator, founded a sports management company, consulted on many business deals in Japan, [both] baseball-related and sports-related, and, as Bob Bavasi likes to point out, also appeared in a popular soap opera, which is something; he’s a man of many talents. Meanwhile, Marty also worked at the Birmingham Barons in the U.S. from 1990 to 1995. He was club president for two years there, and part owner for five years. He had a couple names that a lot of you recognize with the Barons, two-sport stars: Bo Jackson and Michael Jordan, so maybe you can hear about that on this call later. But that baseball experience on both sides of the Pacific led to him being the Tohoku Rakuten Golden Eagles’ first General Manager in 2004, also making him the first non-Japanese GM in NPB history. If that’s not impressive enough, he also holds that distinction in basketball. He is currently the Senior General Manager – and has been since 2018 – of the Sendai 89ers of Japan’s B. League, the main professional basketball league in Japan. So he’s got that role with the 89ers, he’s still a senior advisor for the Eagles, he’s the president of International Sports Management and Consultants, and he also holds various university posts: he’s a professor at Sendai University, He’s an adviser to the president of Tohoku University. Obviously, Marty likes to share what he’s learned with his students and whatnot, and I’m really excited that you’re also going to share with us today. You’ve always been a great friend of JapanBall, so I’m really happy to have you on here so we can all hear some stories and learn from you today, Marty.

Marty:

My pleasure.

Shane:

I just want to start off with [this]: when you first went to Japan, how long was it before you realized that it was going to be a big part of your life going forward?

Marty:

It didn’t take too long. I had my 19th birthday in Japan. My host family had a restaurant in Akasaka called Kisho and [I] had his shabu-shabu dinner to celebrate my 19th birthday, and Japan was just so wonderful from the get-go, so clean, so efficient, people were so friendly. I really enjoyed the experience, so when I came back after that first summer in Japan, when I turned 19, my sophomore year I became the student head of the Keio-Stanford exchange program. You know, it’s what they say in “Jerry Maguire,” they had me from hello, or whatever it is. It started right away.

Shane:

That’s awesome. I just went through this whole resume of impressive things. When you were going to Japan or going to Stanford or growing up in L.A., what did you want to be when you grew up? And was it anything like what has ended up happening?

Marty:

I actually went to Stanford as pre-med, and then in my first quarter, I flunked chemistry, [which] was not a good sign. I was the social chairman of drinking out of the hall that I was in and I was playing baseball, and my priorities weren’t probably where they should have been as far as studies went, so I had to retake chemistry. And then in my second quarter, I got a D, I really improved a lot. At that point, my advisor said, “Kuehnert, maybe you don’t really want to be a doctor.” And I switched majors. I switched to political science… I don’t know why, I had an interest in Asian General, I’d grown up in Los Angeles with some very close Chinese friends in our church. So I went into poli-sci, and the idea of being a doctor went to the wayside, but when I got through college, I was thinking of either going into the diplomatic corps or perhaps business, and after I graduated, I worked at Expo ‘70 in Osaka, and I came back and I applied for grad school at Stanford in an MBA program. I just missed getting in, I was on the waiting list and it was a couple away from getting in, when I got a call from a guy that I had met at Expo ‘70: Cappy Harada. He said that his friend, Mr. Nakamura, had bought the Lodi franchise in the California League, and [if I] would like to be GM of the club. It’s really interesting, I was thinking of going to business school to get a business degree and hopefully work in sports – hopefully between Japan and America – and it was offered to me before I went to business school. So I sent Stanford a letter saying, “thank you very much, but I’ve got the job that I wanted to get after I got out of business school, so I’m taking it.” I did not go into the MBA program, I got out because of Cappy.

Shane:

Well, first of all, I’m a Cal guy, but you’re one of the handful of Stanford guys that I like, so we’ll hold a mutual respect there. Cappy Harada, I’ve learned more about him the last couple of years, and he’s such an interesting figure and great ambassador for the game. Can you talk a little bit more about what your impression was of him, and what it was like getting to know him?

Marty:

Cappy was chosen by General MacArthur after [World War II] to restart [what] the Japanese really enjoyed, the game of baseball. Most of the stadiums had been used as deployment areas for armaments and other stuff, and they were not in shape to be playing baseball games. Cappy was given the job of getting baseball restarted. In the process of doing that, for example, he brought Lefty O’Doul with an All-Star team over to Japan. He also brought Joe DiMaggio and his new bride, Marilyn Monroe, over to Japan. So Cappy was really quite something, and he was a real mover-and-shaker. He would work for the Japanese, get money from the Japanese, and he worked for the Americans to get money from the Americans, he worked both sides very well. He really knew how to get things done, I mean, the reason we became friends in ’70, the San Francisco Giants came – you talk about the tours from American clubs make to Japan – I’m quite sure that when the Giants came to Japan in 1970 in March, that was the first and maybe only time that an American major league team had come to Japan in the spring. Since I was kind of the sports guy amongst them American guides and interpreters, I had the honor of taking Cappy and Mr. Stoneham, the owner, and Willie Mays and Willie McCovey around the American pavilion, and Cappy was really friendly to me at that time. I realized later why he sent me these nice summer gifts – gifts that he would send to me – is because he wanted me to get his VIP friends in the back door at the pavilion, because the Osaka pavilion was an air dome, one of the first largest air domes in the world, and it had revolving doors. A lot of the Japanese people from the countryside have never seen a revolving door, so it was real tough. Some people got stuck in doors, and it took them a long, long time to get in the building – the lines were up to six hours long sometimes. So having a VIP backdoor pass to get in the American pavilion was really important, so Cappy knew that I was a valuable commodity for him, so he maintained very good contact and never forgot to send me those little gifts along the way that showed me how much he appreciated me.

Shane

That’s awesome. I could see why he’s good at getting things done.

Marty:

He was a master, and really skillful at developing personal relationships and getting things done, and Cappy lived a good life because of it.

Shane:

Yeah. So how about when you returned to Japan to work for the Lions? What was your initial impression of the baseball culture there, as far as the professional culture? And how was it adjusting for you? How did you, as an American, involve yourself into the culture there?

Marty:

Well, at the end of the second year – we had had a good year, we won the Cal League championship, and I was Executive of the Year – but Cappy had promised Mr. Nakamura that we were going to be able to move up to AAA, which I think was a lot of smoke at the time. I think Mr. Nakamura realized that after the end of the second year, and he said he wasn’t interested any longer in having a Single A team in the United States. So we were pretty close, and he gave me an option. He said, “you can have the team for the losses that we’ve incurred in the second year – we only had like $6,000 in the red – so you can have the team for that $6,000, or you can come to Japan and work for me, with the new team that I’m taking over in Fukuoka.” He was buying the Nishitetsu Lions, and renaming them the Taiheiyo Club Lions. I still had an interest in coming to Japan. In hindsight, I’d be as wealthy as Bob Bavasi if I had taken the baseball team, but I opted to come to Japan. I’d already been there, and I’d been dealing with all the exchange students that were coming to Stanford, so I felt very comfortable with Japanese people and culture. I knew a fair amount before I went, and I was thrown into it, and I had to learn on the run, but I’d been a GM for two years in the States, so I was able to bring in some new ideas. I did Japan’s first “real” mascot: I bought an actual lion. So we had an actual lion with Taiheiyo Club Lions. We had a naming contest, and the name of the lion was Rara, Rara-chan, and Rara-chan spent its first two weeks in my apartment. It was an interesting time.

Shane:

Okay, I’ve got to hear more about this lion. How big was it? And were there any notable stories of living in your apartment?

Marty:

Well, it was about two months old when we bought it. I found it was easy to buy a lion, but difficult to get rid of one. They get large. We didn’t pay all that much, I think maybe 2, $3,000 for that lion. It was about two months old. Actually, when I arrived at Heiwadai Stadium, it came in a crate, and all of us were scared to death to open the crate to let this lion out. We called the zoo, and some guy came down from the zoo and he looked at the crate, and said, “it’s this small? It’s in this little crate.” He just took off the lid and grabbed it like you’d grab a cat, by the back of its neck and put it on the ground, and said “here’s your lion.” At that point, they’re very manageable, when they’re like two months old or three months old. But the problem was right in front of our very eyes, Rara-chan got bigger and bigger and bigger and bigger. We hired a guy, a veterinary student, to take care of it on his own, and we had a cage built there at Heiwadai Stadium. He would actually put a leash on right before the games, and he was very popular. Now you imagine that one of the big pictures before the game was Rara-chan, but by the end of the season Rara-chan was too hard and too big to handle, and then I [thought], “Well how do I get rid of this lion?” And the Fukuoka zoo didn’t want the lion and all the zoos have got the lions – apparently they breed very rapidly – and so we couldn’t find any takers. And finally, Mr. Nakamura, our owner, had been the first secretary to Prime Minister [Nobusuke] Kishi. And Prime Minister Kishi from Yamaguchi. And he put the screws on the Yamaguchi Zoo to take Rara-chan out of town off our hands. So Rara-chan went on to live – I think – a happy life in Yamaguchi.

Shane:

That’s good. I guess you found out once you had one why it was so easy to get one.

Marty:

Well they breed easily and you can buy one, but when you want to get rid of them. Now most people don’t want a big, wild cat.

Shane:

So there’s a little bit of time between the Lions and the Barons, so I guess I should ask. Were you with the Lions that whole time before Birmingham?

Marty:

No, when I came to Japan, I only stayed one year because I realized quickly that Mr. Nakamura wasn’t interested in making baseball a career. He was only using that team to sell it and make money, because I made a lot of suggestions about doing things, like improving the bathrooms and the concessions and a lot of things to improve the club, and Nakamura never went for most of those. I realized he was just shopping the team, and he in fact then shopped the team to the wealthiest man in Japan at the time: Mr. [Yoshiaki] Tsutsumi, who owned the Seibu group. So I saw the writing on the wall, that I wasn’t going to get to work in baseball because he wasn’t really wanting to do what you needed to run a baseball team. So I was hired by Descente, the sportswear company, in ’75, and I worked for them for five years. I did all their licensing business. I signed up licenses with the NCAA, Major League Baseball, NBA, ABA, Canadian Football League, World Team Tennis, International Track Association, for their marks and logos, and then we sublicensed those marks and logos in Japan, and it was very profitable, especially the NCAA, because I registered the top 100 University marks and logos of American universities in Japan. So we controlled them. And also, Descente wanted publicity in the States that it couldn’t get in Japan. It was so big in Japan, like almost all the Japanese teams were wearing Descente uniforms. They said, “Could you get us a major league uniform?” And I said sure. The first one I got was the Pittsburgh Pirates, with designed uniforms, and then the Baltimore Orioles. You may remember those. if you look at some of the charts about the worst, ugliest uniforms in the history of Major League Baseball, that Pittsburgh Pirates uniform with the gold and the black and the stripes… it’s worth looking up.

Editor’s note: Turns out there have been lots of discussions over the Pirates uniforms in that era, with plenty of kits to choose from. This ESPN article highlights all of them, while Bleacher Report puts two of them on their “ugliest of all time” list. It’s also worth noting that the Pirates have gone back to them a few times for throwbacks recently.

I really created an uproar in Pittsburgh, a union town, because the union folks were not happy about the Pittsburgh Pirates wearing Japanese-made uniforms. But it worked well for Descente. got great publicity in Japan. I got the U.S. ski team and the U.S. speed skating team to wear Descente uniforms. Eric Heiden at Lake Placid had a big Descente across the hood of his racing suit. And then I got the U.S. volleyball team, men’s and women’s, to wear Descente volleyball uniforms. I did a lot of the uniform supplier jobs for Descente too, so that was a fun five years from ’75 to ’80.

Shane:

I knew there’s a little gap in there in the bio that we didn’t have. That sounds like an interesting time. So before we get to Japan, I just want to talk quickly about Birmingham. How did you get involved with their ownership group? And then you’ve got to share something with us about Bo Jackson and MJ.

Marty:

I wrote a number of books about Japanese baseball, and after ‘80 I started my own company, a consulting company, and I did broadcasting and writing, and wrote a couple books. One day I got a call from my buddy who I had known since college, Gary Saji, who is the owner of Suntory, and Saji wanted to buy a Japanese team; he specifically wanted to buy the Hanshin Tigers. The Whales were considered top and he said, “what would you recommend to do if we wanted to buy a team?” And I said, “Well, you’ve got to work a lot of banks and you have to work in the back rooms and so forth, but, if you really think you can buy a team and you want to prepare, I suggest that you buy a minor league team in the States, because Japanese teams are always ripped off by the major league teams that sell them players that they think are such great players, guys that they tend to put on waivers the next week for $25,000 is suddenly worth a half a million or a million dollars. If you become part of the baseball family in America, you’re not going to get ripped off like you would be if you’re just a guy from across the pond. Also, if you have a ballclub in the States, you can have a place to train your coaches and trainers, send young players and just have the all-around benefits of having a team in the States. And by the way, franchise values are going way up right now.” So Gary Saji said, “Well, what team would you recommend?” So I went around the States and looked at all the teams that I thought were the best candidates, and I thought the Birmingham Barons were the best team to buy. So we bought the Barons. I told him about all these benefits, and the interesting thing off the top of my mind, if I could have told him, “And in our very first year, the number one two-sport athlete in the history of America is going to play for our team,” who would have believed it? And then if I said, “and get this, five years later, one of the greatest athletes ever is going to quit basketball and come play baseball for us.” Who would have believed it? But it happened.

Shane:

So I think you proved it was a good choice.

Marty:

Yeah, it worked out well.

Shane:

I want to get to the Eagles, but we have a hand raised by Robert. So I’m just going to go to Robert here first so he can ask the question.

Robert:

Good to see you. I still have one of these. *shows Marty a towel from Kuehnert’s sports bar, “The Attic.”

Marty:

Oh The Attic! My old sports bar. You know, my employees and the fans of that original sports bar in Japan still get together every year to have a party commemorating the good old Attic days.

Robert:

I can’t believe it’s been so long. I wanted to ask you when you did your Heroes’ Bar Interview show, did you have any player that stands out or did anything exciting happen? I remember I think you mentioned when you interviewed Ichiro, you were surprised by the way he was dressed?

Marty:

Yeah, he was trying to always be cool and wear the kids’ stuff, but actually Ichiro at my interview really went well, if you look back at it. It was only in his third year, it was his breakout year. He was already known to be a tough interview. If he didn’t think the interviewer knew his or her stuff, it could be pretty cold. But I knew him because I had been broadcasting for both Kansai TV and Sun TV, so I’d seen him on the field, and we talked. He was always telling me the newest dirty words that he had learned from his foreign buddies. I think already from the beginning, he was planning his career and planning to come to the States, so he learned a lot of English, and of course, he learned the dirty words, first; he was really funny actually on the field. I think it was right after that first season in the States, he did the Bob Costas “Up and Close interview, and Costas asked him at the end of the interview, “What’s your favorite English expression?” And he started laughing. He looked over my friend Bob Turner, who’s his interpreter-manager. He said, chuckling like, should I say it or shouldn’t I? And he said, in August it’s hotter than two cats f***ing in an old sock.

Editor’s note: you can check out the clip for yourself here; viewer discretion is advised.

And Bob Costas burst out laughing, and Bob Turner was trying to get him say “You can’t you can’t put that on,” but it’s HBO so it ran. He actually turned it around a little bit, but that’s what he meant to say. But anyhow, I think the one interview that probably stands out more to me than any other was the one with the Sadaharu Oh. In fact my dear departed friend and all our friend, Wayne Graczyk, his wife said she started crying when she heard the response. I asked him a question that most people won’t ask: about his nationality. It’s kind of a taboo subject that most people won’t bring up, but I brought it up in a way that he was fine with. I said something to the effect of, “I know that I’ve heard that you really respect your father, that he worked very hard in Taiwan to make money and get your family to Japan,” and he said, “No, no, it’s Mainland China.” And he just opened up to it right away. I said, “I also understand you haven’t taken out Japanese citizenship,” And he said, “Yeah, that’s right. Everybody knows I’m Chinese, I was born into a Chinese family, and I’m fine with that. There’s no problem, and I respect my father, and it’s a way of showing respect to my father and all that he did for us, by just keeping my Chinese citizenship.” But while his dad was born in mainland China, his actual passport is a Taiwanese passport. It was a subject that most people don’t want to discuss. But, I found that while interviewing people, if you ask them in a nice way, you’re pretty much gonna get good answers, and often times the answers that you want.

Shane:

Thanks for that question Robert. I want to talk about when you got hired by the Eagles. What did you view as your first priority when you signed up for that job?

Marty:

Well, the first priority was, number one, getting a staff in line. And actually, [Hiroshi] Mikitani had already had in mind who he wanted as manager, it was fairly public, the guy that was a star for the Hanshin Tigers, and you know, Mikitani was from Kansai. And actually, even some publications have already said that he was going to be the manager, and I said, “Mr. Mikitani, I don’t know. Have you checked into this guy’s background? Do you know why he hasn’t become the manager of the team that he used to play for? He’s rumored to have lady problems, alcohol problems, association problems with underworld figures, and the list went on and on, and I wouldn’t recommend it.” And so Mikitani did his due diligence then, and the next morning, he says, “okay, who do we sign?” So then I did my search, and there were a lot of people that we had on the list, but I liked [Yasushi] Tao, because Tao was still young, very energetic, very active, and a good player, and I thought with the club that we’re going to be forming, that I had to start running from the get go, that he could run with them. I liked Tao, I had worked with him at Fuji TV quite a bit, and so we chose Tao. But then we had to do next was to select the coaches and scouts, the staff that we were going to have with the ballclub. So that was the first thing, putting the thing together with the staff. And then we had to, of course, start looking at how we would draft, and we spent a lot of time on who we we’re going to draft. But we really started in a big hole. In the States, they have an expansion draft, where you can choose a couple players from each team. Here, they gave us a dispersion graph of the dregs of the worst two teams in the Pacific League. So, I mean, what a hole. We had to start with guys that were completely left over, because the new team, Orix, was able to keep the top 40 guys. We started Number 41, other than [Hisashi] Iwakuma, who we used a special deal to get, and [Koichi] Isobe, we really got only two star players to start off, and that’s tough.

Shane:

Sounds like it. So, I guess it seems like a known thing that you brought in largely in part because you weren’t part of the old school NPB regime, and then you weren’t really given too much of a chance to implement it. So what do you think happened there?

Marty:

What happened is, Mr. Mikitani is like George Steinbrenner on steroids, I think. One of his expressions for his company, Rakuten, is speed, speed, speed. He has posters on the walls, everything is supposed to be done fast: speed, speed, speed. I think Mikitani-san thought, with his business acumen, that he could change things right away and that we could do amazing things in spite of not having the horses to run with. We got the dregs from Kintetsu and Orix, and then he further tied my hands by saying, “Let’s build this team from the ground up with young players, so don’t spend over $500,000 for a foreign player.” And I’m saying, “Mr. Mikitani, we’re not gonna compete if we can only spend $500,000 for foreign players.” Two guys that I wanted – I wanted to get Andy Sheets, who had become a free agent from the Hiroshima Carp. This is like having a big shortstop, a Cal Ripken kind of shortstop, who can hit your 30 home runs. And then [Roberto] Petagine, who is gonna give you 40 plus home runs, was available from the Swallows. I wanted to sign those two guys, I figured that if I signed those two guys, I had 70 home runs in my lineup, and that’s something to build on, since I had so little that we were getting. But he didn’t let me do that, and then when we lost the 11 straight [games] in April, we were the slowest team ever to get to 10 wins. But when we lost 11 games in April, suddenly he wanted to demote me, wanted to demote the head coach, the manager, Kumada, our hitting coach, was demoted. Actually, he wanted to change Tao too. So to say that he is impatient is putting it mildly. I mean, he just felt I wasn’t performing. So somehow, I was supposed to take these players and magically have them win. We were lucky to win 38 games. If you think about it, in 2013 when we won at all, Ma-kun – [Masahiro] Tanaka – won 24 games, and [Takahiro] Norimoto was Rookie of the Year with 15 wins. Those two guys won 39 games by themselves, when our entire pitching staff in 2005 could only win 38 games all year. So we just didn’t have the players, but he didn’t understand that and he wasn’t willing to put up with that at the time. So he’s actually infamous with his soccer teams for changing his managers every year. One year, I think he changed managers with a soccer team, they had three managers in one season. So he’s not a patient man, if I had to put it mildly.

Shane:

Wow. So if you did have more time to implement your visions, what were the things that you envisioned doing differently than the way clubs have been run in the past in Japan?

Marty:

I would want a training staff that didn’t believe that having players run more was the answer to everything. Here in Japan, [Masaichi] Kaneda – the famous 400-game winner – I often broadcast in a booth next to him, and he always came late, he didn’t do any homework on the players. If a pitcher wasn’t pitching well, hashirikomi ga tarinai – he didn’t run enough. If a batter wasn’t hitting well, hashirikomi ga tarinai – he’s not running enough. Old-school answer. If they’re injured, they need to train harder too. One of the things that I did in the beginning was trying to bring in a good medical staff that would try to take care of the players in the way that they really had to be taken care of, but not to burn them out. In those days and before, a Japanese player hit 30 and he was done, because he’s played baseball every day since he was about 13 years old from morning till night. I really think there was a factor of early burnout in Japan. A lot of times now, players don’t hit their stride until they’re 30, but then they were done. So I thought, from a medical standpoint, I wanted to see that we do things more scientifically. And then scouting put a lot of emphasis on scouting. People go to Koshien and watch the Koshien stars – actually at the time, there weren’t any of the independent leagues, – but there are good players in Japan that are missed sometimes, and so I thought that we could make some changes with scouting.

Shane:

And do you feel that their organization, or the league in general, still needs to evolve in that way? And are there certain organizations that you respect for their willingness to do things like that you just mentioned?

Marty:

Yeah, I think things have gotten a lot better, and the Pacific League has had a lot to do with that. It used to be that the people only looked at the Central League, and then the Pacific League started to become innovative, and that caused the Central League to follow suit. I’ve been watching Japanese baseball for over 40 years, and in the old days, it was really the Dark Ages. It used to be that when you went into the office, like when I first went into the Hanshin Tigers’ office 40 years ago, it was full of guys smoking and reading newspapers sports papers. It was not a very business-like organization. In the old days, almost all the people working in the front office would be former players that had been usually brown-nosed kind of guys, or guys that were kicked down from the parent company. People weren’t brought in from advertising agencies or from marketing companies and so forth. I think today when you look at organizations, you see a lot of businessmen that have been selected in the front offices. I know when we asked to fill 30 Eagles’ spots, the salesman spots for the Eagles in our first year, we got 8,000 applicants. These are guys from outside, and aren’t baseball guys, and we didn’t choose many of what you would call baseball guys, we chose more business people. So I think that the organizations have gotten much better. You can see that actually, it used to be that in Japanese baseball, only the Giants and Tigers, because of their long history, made money. For years and years, it was only those two teams, everyone in the Pacific League lost money, and the other four teams in the Central League essentially lost money; not true now. I’d say almost half the teams are making any money now, and it’s because they’re so good at what they’re doing now. I mean, look at Yokohama, DeNA came in and turned that club around completely. It used to be empty, nobody there at all, and it’s a wonderful ballpark now, and they make money. And now they’ve gone into basketball. They bought the Kawasaki team in basketball and are doing the same thing with Kawasaki. So I give them credit for their management skills.

Shane:

That’s a great insight, and it’s a good setup for a question in the chat from Kyle in Honolulu. You kind of answered this already, but maybe you can expand: what is the current overall health of Japanese professional baseball from the popularity and financial standpoints?

Marty:

Well you know, the COVID-19 pandemic killed sports overall, for sure. Last year, the Eagles lost about $50 million and Yomiuri Giants and the SoftBank Hawks lost about $100 million dollars, because here, the revenue from tickets is much more important than in the United States and Major League Baseball. Everyone knows in the states that the large income is from TV and broadcasting rights. Here, it’s miniscule, TV and broadcasting rights, the big money’s not paid. There are a lot of little deals done with a lot of different broadcasters, like with the Eagles’ broadcasting income, it might be the 10th source of income, and tickets and sponsorships are the things that pay the bills. With tickets that was shot out of the water this last season, and it’s a problem now too, so until they can get people back in the ballparks and start filling the ballparks again – like with the Hanshin Tigers [when] every single game and every seat is full in normal – until they can do that again, there’s going to be some hard times for Japanese baseball. So this COVID-19 pandemic has really hurt baseball, but most of the companies are owned by big companies that have staying power. So I’m assuming that eventually this will get back to somewhat of a normal situation, but right now, I don’t think anybody in Japan is making money right now.

Shane:

I’m hoping that it motivates some of the powers to be to make the games more accessible on TV, especially internationally. I know a lot of people feel that way on the chat too, especially Gabe, who’s mentioning it here.

Bob:

Hi there, Marty. I love the game you set up for us years ago with Shohei Ohtani and Masahiro Tanaka. That was a pretty good game.

Marty:

I knew that JapanBall was coming, so I ordered that for you guys. It was pretty good.

Bob:

The question I have is, one thing I kind of admire with the Japanese game is the draft, where teams [can] draft the same player, and then there’s a lottery to find out who actually gets that player. The second part of the question is with Shohei Ohtani; I don’t know if you’ve had any input into whether to draft him or not, but did the Eagles draft Ohtani when he was available? And of course, what’s your opinion of the whole draft system in Japan? Did you like it?

Marty:

Overall, I don’t like the draft system. I think the waiver system where you try to even out the talent and give the last place team an opportunity to draft this stuff tends to balance out the talent. If you look back at the history of the draft, it’s always been changed by Yomiuri trying to fix it, so they can get players – if they don’t get the players they want, they change the draft system. Unfortunately, Japanese baseball still does what the Yomiuri Giants want to be done. You know, I’m embarrassed with Shohei… I’d have to go back to that draft to see who we chose. I can’t remember right now, I’m going to plead ignorance, because for the last three years – it’s been longer than that – I’ve been focused more on basketball than baseball. I’d have to look that one up. I can answer it later on. But I think everybody wanted Ohtani So I think our hat was thrown in. Maybe Michael or somebody remembers better than I did. I don’t remember if we were in the top group. I think we were.

Bob:

And the other thing: I guess there’s a strategy for that whole system. So if everybody wants Ohtani and you want somebody that’s pretty good, and you want to take him, I guess you would select him rather than going into that [lottery?]

Marty:

Yeah, that’s absolutely done, and we’ve done that in the past. Other teams do it, too. They know that, [Teruaki] Sato – the big gun that went with the Hanshin Tigers this year – everyone was going to take him and you’ve got a pitcher that might be available, because [everyone’s] going to go after Sato, then you do that. So that definitely does happen.

Shane:

Could you talk a little bit more about that, Marty? About the draft and the positioning, pre-draft discussions and whatnot?

Marty:

Well, Japan is a small country, so I think the scouting is pretty good. I said earlier that scouting is important, and some guys might slip through the cracks, but it doesn’t happen nearly as much in Japan as it does in the States, because the States is so huge, and there’s a lot more players to cover. Here in Japan, it’s very regimented, so we know all the players for all the good schools, when they’re going to play, and it’s relatively easy to scout them, Occasionally now and then the dokiritsu league – the independent leagues – are coming up with a couple ballplayers that have been missed. When we started, we had eight scouts – I think they may have 10 now with the Eagles – and those guys, they break up the country into different sections. Each of those scouts has one area to cover – similar to the States – and are asked to send in reports for every game that he does, and that’s cool, they’re using a lot more a lot more analytics now. Obviously, that’s changed in American baseball too, so it’s actually quite similar to what’s done in the States. I don’t think it’s all that much different and actually, in some respects, I think it’s easier to scout here, because of the country being compact.

Shane:

Gabe says the Eagles picked Yudai Mori in the first round. Ohtani was uncontested by Nippon-Ham, because he declared he wanted to go straight to MLB.

Kyle:

Hi Marty. Major League Baseball has seen a lot more home runs and strikeouts recently. I’m just wondering if the Japanese game has changed at all in the time you’ve been there.

Marty:

Yeah, what you see right now, with the boom-or-bust kind of situation. Just look at Teruaki Sato with Hanshin, he’s doing the same thing.

Editor’s note: Teruaki Sato, a rookie with the Tigers this season, is getting plenty of attention for his hitting ability, including a ball that he hit out of Yokohama Stadium. Sato’s power-hitting approach is a bit different from what has been expected of Japanese players traditionally.

Some old timers are complaining about him striking out so much, but most of the Hanshin fans love to see that ball sailing over the fence; he’s just amazing. But he’s swinging very much like the big guns in the States do right now, so I think it has changed. There are some bigger kids here now, so that’s changed because they’re bigger and they know they can hit the ball out of the ballpark? The smaller players are still pretty much Punch-and-Judy kind of hitters, because they know they can’t hit the ball out of the ballpark, so it has changed a little, but you look at the size of the players in the States, they’re monsters. Here and there, you have a guy like Sato, that really is just incredible. He’s built like a truck, and he’s also got an attitude that says, “I’m a star,” he just looks very content in his own skin. And here and there, you see players like that: [Sho] Nakata with the Nippon-Ham Fighters is that kind of player too, you’ve got usually one or two young guys like that. But in the States, you’ve got eight guys in the lineup sometimes like that. So I think I have seen things change, but the approach is still pretty much the same. Usually if the guy gets on they’re gonna bunt him over and some habits die slowly.

Yumi:

Hi. Because I’m a big Yankee fan, Masahiro Tanaka came from Rakuten to the Yankees. But then I noticed that [there are] some Yankee players who could be in the big leagues and minor leagues, kind of back and forth, like players in Andruw Jones, who went to Rakuten. Is there any connection between Rakuten and Yankees? Some players in the past, especially like the Yomiuri Giants, the team sent some players kind of like an exchange student program: the players go to the Yankees to learn in American League or whatever. But that’s just for a short period of time. But the trade with Ma-kun (Masahiro Tanaka) when he came to the US, and Andruw Jones and a couple other players, I noticed that they went to Rakuten. Is there any connection?

Marty:

Since I haven’t been on the inside very much for the last three years, I’m not sure. But here and there, the Eagles, like most clubs, have signed working relationship agreements with different clubs. I know we’ve had one in the past with the Texas Rangers, the San Diego Padres. It wouldn’t surprise me if we had done something with the Yankees. But usually those agreements are more for, as you’re saying, “Your people are welcome to come to spring training, you can send over coaches to learn how to coach with our team.” But you can’t you can’t force the players to go from one team to another because of the current agreement between the United States and Japan.

Yumi:

Also the staff members from the Giants, it’s kind of like school with the exchange program.

Marty:

The Yankees for the longest time – at least for 30 years – had an agreement with the Nippon-Ham Fighters. I actually wrote about it, that I felt it wasn’t doing them any good, because the Yankees would just pass off players they didn’t want anymore to the Fighters, and those guys just weren’t successful. An interesting thing was… if you remember, when Irabu wanted to go to the States, they basically said, “Well, we’ve sold him to the Padres.” And Irabu said, “I’m not going to the Padres, I want to play for the Yankees.” It became an international storm over that, and in fact, that’s when they came up with the new rule for being able to bid on players, and that opened things up to the current system. So, he actually didn’t want to go to the Padres and wasn’t able to be forced to go to the Padres, and he went to the Yankees.

Yumi:

Actually, I was at his first game at Yankee Stadium. I didn’t even know who Irabu was because I’m not a Hanshin fan, and there was no internet, I didn’t know anything. But my coworkers knew him from the Hanshin Tigers, and said that he was going to pitch, let’s go. So I just went, and I saw his first game with the Yankees.

Marty:

Minor thing, he didn’t come from Hanshin, he came from Chiba Lotte; he came from the Marines. At that game, you didn’t see him spit at the fans – that came a few games later. I think his first game, I think he won. He did well in his first couple of games, but later when the people started booing him, he wasn’t very happy about that.

Yumi:

No, I remember that year, because at the end of the year, his t-shirts were sold at $5. I was really wondering if the Yankees or Rakuten or the Nippon-Ham Fighters had some kind of training programs; that kind of makes sense. Thank you so much.

Marty:

Currently with the Nippon-Ham Fighters, [Hiroshi] Yoshimura, their general manager, went to Detroit and worked in the front office, and now the former GM of the Detroit Tigers is now in his retirement working. So there are relationships, definitely, but they’re more for front office stuff, marketing things, training of staff, then actually passing along players, although those organizations do recommend specific players for the organization here. Sometimes it’s not even just their players, they’re sometimes saying, “Well, this is a really good player on another team [in their respective leagues], and we recommend you look at this guy,” and that does happen.

Gabe:

Good evening, Marty. My quick thing before we get to my question, though, keeping on the partnerships thing… When I was at the Koshien Museum in 2019, I noticed that the Hanshin and Detroit Tigers have a friendship agreement in place from like 1988 or so, saying “We agree, we’re good friends, we’re competitors, we want to grow the game of baseball.” It was neat, and nobody threw a lawsuit over the team named Tigers, so nice. I wanted to ask about your abilities and transferable skills going from a baseball general manager to a basketball general manager, and what those look like. Was it just like sliding into a new pair of shoes, or was there a bit of a learning curve?

Marty:

There is a little bit of a learning curve. Much of it’s similar, but I found out that your personnel decisions in basketball are really a lot more important in many respects than your personnel decisions in baseball, because you’ve got fewer spots to fill. We will only sign 12 or 13 players for our basketball team, whereas with the baseball team, you sign a minimum of 70. You’ve got some room to grow players to make mistakes, and it’s not gonna hurt you or kill you. But in basketball, you make a mistake or two, you only have five guys on the court – it can kill you. Just this past season, we were in the running, we made the playoffs, but before the playoffs, we lost our number one point-getter, Le’Bryan Nash, an old Oklahoma State star, and that hurt us in the playoffs. It’s a wonder. Just one player can make a huge difference in basketball, and certainly two, and usually you’re not going to have that much of an impact in baseball. It just showed all the more importance about trying to make the right decisions. But making the right decisions, it’s a shot in the dark sometimes in basketball like in baseball; you just don’t know who’s gonna be successful over here, necessarily. But you can see the stats in the States, and you can have everyone in the world tell you, “Oh, that guy’s gonna be great in Japan, you gotta have the guy come” when he’s not. There’s just many unknowns, you don’t know what’s going to happen until the actual situation. But yeah, it’s a lot similar, but I think there’s more there’s more pressure on and making sure you make the right decisions on personnel.

Gabe:

If I may tweak some baseball fans’ noses, there’s an excellent comparison. If you have two generational talents and a bunch of bums on a basketball team, you have a championship contender. If you have two generational talents on a baseball team and a bunch of bums, you have the Los Angeles Angels. Thanks for answering the question.

Shane:

Thanks for that Gabe. I was curious, I wanted to ask about that, too. You mentioned how you can know the stats and the talent, but you don’t know if he’s gonna succeed. Is there something different between basketball players and baseball players who are import players in Japan, and what makes them succeed as far as off the field or off the court? Are they the same traits?

Marty:

Yeah, I’ve heard many of your other respondents to this question, and it is really all about character. I had an agent push a really good player last year, and right away, I did my due diligence and read all I could about that player, and then found out that he had been arrested not long ago for domestic violence, and it was a pretty public case. I discussed it with our owner, and said “we don’t want a guy like that in our organization.” We had another guy we looked at last year – again, a really good player – and he was in Israel, and he spit on a referee. I knew Robbie Alomar, who’s a major league umpire, and Robbie Alomar is a terrific guy, but nevertheless, you do something like that, that mistake stays with you for the rest of your career. So we really look for character, and how good the guys are. We did that in baseball, too, and I got two guys that we had here with us in the season: Danny Miller, who was out of Georgia Tech, and Eric Jacobson, who is out of Arizona State. Both first class people, not just really great players. So when we talk to people about them, what kind of guys are these? It’s always a question we ask, because we can see the stats, and we can see the videos of how they play, but you need to talk to the people who know them as people to find out about their characters. That’s no different for me in baseball as it is now in basketball.

Margaret:

Hi Marty. Because of my work. I’m fortunate enough to go to all 30 ballparks. All the old-timers will ask me about [Kazuo] “Pancho” Ito? Is there a person that is close to being Pancho Ito?

Marty:

No, he’s irreplaceable. There’s nobody like Pancho. He had a photographic memory. I remember we were watching one a vintage film, and it showed Babe Ruth swinging, and it was talking about what year it was. Pancho says, “that’s wrong! That didn’t happen that year!” I said, “What?” Pancho says, “The [Yankees] didn’t put numbers on until like a year later.”

Editor’s note: Kuehnert is referring to the film showing Ruth, wearing the No. 3 he became well known for late in his career, hitting his “60th home run” in 1927. Pancho knew it was not the actual home run because the Yankees did not begin wearing numbers until 1929.

He knew everything. He could tell you about what happened in the 1952 World Series: what happened, the result of the series, the starting lineups for both teams, and everything that was done, he could remember at all. And besides the memory that he had for a love of baseball, he just enjoyed communicating with people. I remember when we were meeting in Hawaii at the Sheraton Waikiki and I remember that Mr. Matsutarō Shōriki, the owner of the Giants walked in when Pancho was holding court, talking to a lot of people, all the GMs knew him knew him, and a lot of people knew him. Mr. Shōriki walked in, and nobody left Pancho’s group to go over to greet Mr. Shōriki Many of you probably didn’t know he who he was, but you know, everybody knew Pancho, and everybody loved Pancho and he was just just the greatest. It was a big loss to lose Pancho, it really was.

Margaret:

Arrigato. I was texting with Don Nomura. He says hello to you.

Kyle:

Hi Marty. Masahiro Tanaka said his wife and children experienced racism in the United States. Just wondering if that was played up really big in the Japanese media, and what is your reaction to the situation considering you know him, and also since you’re from the United States?

Marty:

This whole thing with the racism in the States is just so upsetting. Not only have I been married to a Japanese woman, I lived most of my life in Japan, and my sister married a Mexican and has lived most of her life in Mexico. So I’m sensitive to other cultures, treating everybody the same. So I just don’t understand the racism in the States. I helped [Rui] Hachimura tomorrow go to Gonzaga University. He started part of this storm recently, and his brother actually started over here – his brother who’s playing now in the B. League, Allen Hachimura – said he gets racial insults all the time, and then said “there’s not a day that doesn’t go by in the States that Rui doesn’t get them.” Just shame on us. Shame on Americans for doing that. It’s just horrible. I mean, the only people who aren’t immigrants to the United States are the Native Americans; we’re all immigrants. We all came from someplace. I just don’t understand the Trump mentality [that] Mexicans are rapists, and just p***ing on all minority groups. It’s just crazy. So it’s gotten a lot of pressure. Hachimura has been doing so well with the Washington Wizards, that really got a lot of attention here, and then as a result, when Ma-kun (Tanaka) made his statements and Naomi Osaka has made her statements and people are just open about the fact that their racism is is blatant in America, but unfortunately, as blatant in Japan too. Allen Hachimura was getting those racial taunts here in Japan. So if you’re a minority in Japan here, especially a Chinese person of Chinese background or Korean background here, those people get a lot of insults. It’s unfair, it shouldn’t happen.

Shane:

Thanks for sharing that Marty, I definitely agree with you there. I’m curious: you’ve obviously spent a lot of time working with students. What are the themes that permeate your teachings?

Marty:

With my classes, I try to have them understand the cultural differences between American society and Japanese society through sports. Actually, next time I have the opportunity I will use Ema Yamazaki’s Koshien. Until now, I’ve been showing my students the thing Alex Shear did on Koshien, which came out probably almost 15 years ago now. If you guys haven’t seen it, I think you could probably pull it up and take a look at it. Ema’s piece was fantastic. I think she spent more detail, [and made it] more cinematic in a way than Alex’s piece. But the Koshien one that he did was really good, and it just shows the passion and the dedication of baseball players, with the moms getting up at four in the morning to make the bento, the kid can get up in the morning and have morning practice, going all day long and practicing until the wee hours, and doing that almost 365 days a year. I show the students that kind of thing and say, “This is not just baseball, all sports in Japan are run this way. If you’re on a soccer team, it’s going to be the same. If you’re a rugby team, it’s going to be the same. There’s no difference.” I try to point out, in all my classes, the cultural differences. I say “Okay, we’re going to go to a game tonight and we’re going to see the Eagles play. A lot of the guys on the Eagles will have been drafted by the Eagles, and will stay with the Eagles until the end of their career, and that’s over.” In America, it’s hard to find a major league player now that’s spent his entire career on one team, it just almost never happens anymore. So there’s a loyalty factor, and I try to point out to them in the States [that it’s] all about money. One of the things that people ask me is what I like about baseball and sports here, I like the loyalty factor. I like that people feel that they owe something to the organization that brought them into the game, and the way that juniors respect their seniors, this senpai-kohai kind of system, a younger player is deferential to the older player. I don’t think you see a lot of that in the States; a little, but not a lot. So anyhow, when I’m teaching the students, I really emphasize very strongly that we see a difference in cultures as seen through sport. It shows you a lot about the society, and Robert Whiting’s books are so good, because it’s not just baseball, it’s about society. By the way, I haven’t got his new book. I’ve got too many piled up right now that I haven’t finished, but I’ve got to get his new book, which I understand is sensational.

Ian:

Hi, Marty. I remember from a Jim Allen chat that the Eagles did not draft Yu Darvish, and I was wondering if you could talk more about that, and that Bobby Valentine has talked a lot about having a better minor league system in Japan with more teams, and I was wondering if you agreed with that? If you do have changes, what are they?

Marty:

Both very good points. You bring up my biggest embarrassment as a general manager. At the end of 2004, when we were trying to decide who we’re going to draft, we had this choice. Do we draft the number one college pitcher in the country, who we think can step in and play for us right away – who was [Yasuhiro] Ichiba pitching for Meiji University – or do we pick up this young wild kid pitching for Tohoku High school, by the name of Yu Darvish? Unfortunately, Yu had a kind of a bad reputation and he was so good that he would blow off practices and go to the pachinko parlor and smoke, and do things that didn’t help his reputation much, yet as a talent, he was clearly better than Ichiba. We chose the guy that we thought was more solid, and that could help us right away. So we chose Ichiba, who right after we signed him, called me up the next day and said, “my girlfriend’s pregnant.” It was not a good start to things. And then he also lost his first nine games, he didn’t win a game until September, and then Darvish, in his first year, won five right away when he’s only 18. So I often think about if we’d had Darvish, Iwakuma and Tanaka on the same pitching staff, how unbeatable we would have been. As the general manager, you make some good decisions and you make some bad ones. I picked Yamazaki Takeshi off the garbage pile. Orix said that he had nothing left in the tank, and he was 36, and he can’t play anymore. Actually, Don Nomura represented him, and Don begged me to take him, and let us sign him for a huge drop, from $1 million to $500,000, and then three years later, he won the home run title and RBI title. He was our power for the first six, seven, eight years of the team. So yeah, you make some decisions, you make some bad ones, the one with Darvish, if I had to do it over, I guess you know what I would have done. But then the other thing… Bobby was very vocal about wanting there to be a third tier of minor leagues, not just the ni-gun (farm team), but the san-gun (third-tier). I was in total agreement. Bobby and I always didn’t agree about everything, but in that subject, we definitely agreed. Right now, the money teams – SoftBank and Yomiuri – they do have a third team, and then that third team plays against colleges and Independent League teams, against themselves or against their second team. I think Japan would be well served by having a third tier, I think they should do it. But right now, teams are not making money so I certainly don’t think they’ll make that move now, but down the road, I really think they should.

Iain:

Yeah, I agree too. The more players you have, the more people who want to play baseball. Sorry for bringing out the Darvish story, I’m just a big fan.

Marty:

It’s alright! I watched him pitch yesterday and said, “Jesus, we could have had that guy.” But anyhow. No one’s perfect. Right?

Patrick:

Hey Marty, just a quick question. I know we’re almost out of time, but with this Naomi Osaka media controversy recently, my question to you is… from your GM days in Rakuten and all the way to now, how did the Japanese media treat you as the first foreign manager and throughout your career? And the second part is, would you say the Japanese sports media is tougher than American media in interviewing sports personalities?

Marty:

The first part of your question: I remember that, since I was a foreigner, like when I joined the front office of the Taiheiyo Club Lions in 1974, all the media wanted to talk to me. I was not top on the totem pole of executives, and it actually caused friction in the front office; the general manager and president weren’t happy that people wanted to get answers from me and not from them. I actually had to start asking the media, and tell them that that’s not an appropriate question for me, you need to talk to the President, you need to talk to the GM. I had to be sensitive about that. I think, if anything, if you’re a foreigner here, then the media wants you all the more. They find it the differences in culture and how you’re adapting, what kind of Japanese food you like a big deal. The media here is very interested in foreign players. And then for the second part… I’d say they’re much tougher here, because there are the national sports newspapers, whether six or seven of them, and they don’t have that paper in the States. These guys have to come up with a new story every day, so they just cover the players like hawks. One of the industry stories you guys will probably find amusing is that Randy Bass came home to his home in Kobe one day, and when he opens the door, there’s a photographer standing on top of his steps, taking pictures in his house. There’s a lot of pressure on them to come up with stories, and especially when you’re like Randy was, a triple crown winner and the Hanshin-crazy fans, they couldn’t get enough of Randy Bass. I think the reporters go to real extremes to get stories. You wake up in the morning and come out of your house, as a reporter there. [Akira Kuroiwa] Matsuzaka found out the hard way that the press is always going to be there. In his first year, when he was 18, he went to his girlfriend’s house – who’s now his wife, a former announcer – parked outside her place, and when he came out in the morning, his car was gone, it had been towed away. The problem was that Matsuzaka didn’t have a license at the time, it had been taken away from him for speeding. So Matsuzaka got his [talent] manager, , who had been a former speed skater in the Seibu organization, [he] went to the police box to say that he had parked her car. The entire thing had been documented. There were reporters waiting out, who had followed him to her house, taking pictures when he got in and taking pictures when he came out. It was all public. This continually happens in Japan, there’s not much of a private life when you’re an athlete, especially if you’re a popular athlete. The media is going to be all over you.

Kyle:

Okay, Marty, who do you think is going to be moving from Japan to the United States to play baseball in the next few years? And also, how does the postal system work now for MLB teams trying to acquire Japanese players?

Marty:

The posting system, they keep talking about changing it but I don’t think they have; I think it still remains as it was. There’s always threats, both sides say they don’t like it, but they don’t seem to be able to come up with something new that they do. As for players who are going to go, if you look at the top players on each of the teams, they’re pretty easy to identify. [Takahiro] Norimoto on our team, a lot of interest in him, he’s been really good… not as well this year as maybe last year, but I’m assuming he is doing well this year. I think there’s lists you can see on the internet where people pick out the players they think are gonna go, there’s always going to be maybe 10 players, usually you’ve got one player per team, on average, that is really on the radar of Major League teams. I’ve said in the past, I see these funny comments sometimes, “it’s a goal of all Japanese players to play in the major leagues.” And that’s totally false, because 70-80% of the players know that they couldn’t play there. Now, of the players that know that they can probably play, I think that they would have a good chance, the majority of those players would like to have a chance to go. But anyhow, I’d need to go through the rosters, and I could pick out and even send you an email later on who I think are the guys that have the best chance of going on, but I don’t have a complete list on that now.

Yuriko:

Hi Marty! One of these days, you and I will actually get to meet, but I would love to talk to you at some point. I’m just curious, since you’ve been doing this for a while. What do you see is the difference between when you were first working in Japanese baseball, in terms of like foreign players coming in and stuff, what sort of has changed the most from then to now?

Marty:

One of the biggest changes is the number. When I started going for those years, there were only two players per team. I used to know all the players that were here and know all their names, and now like that question a moment ago, I get stumped when asked about players’ names, there’s so many of them. Teams have anywhere from probably a minimum of more or so of five, and a max of maybe eight, even nine sometimes. I was looking through our rosters over the last 16 years for the Eagles, and I can’t remember a couple of guys on the list, they were here for such a short period of time. So one of the big changes is the sheer number, that you can have four on the first team and unlimited on the farm team. Some organizations that are wealthy take advantage of it, especially like SoftBank or Yomiuri Giants. I think that the scouting of foreign players has gotten better. I remember that some years ago – probably 30 years ago – the Hanshin Tigers had a Latin player show up at the airport in Osaka, and he came off the plane on crutches; they had signed him and didn’t know that he just had a major injury, and you think that they would have known that, but they didn’t. That’s kind of how scouting went, somebody recommended somebody, who recommended somebody, and they didn’t check with their own eyes. Now I think all 12 of the organizations now have their own scouts in the States. We have three and probably most organizations… probably that’s the average about three scouts, some have more. But so the scouting is good now, so they know who they’re getting, they have a little better idea. But again, as I mentioned earlier, even though you know the stats, you know how they’re playing over there, it’s not a guarantee that the guy’s gonna fit in and play well here, and the trigger is so quick here. They pay him a lot more money, so they’re expected to produce sooner. Jeff Manto is famous with the [Yomiuri] Giants, he got in 10 at bats and 10 games, and he was gone. Some players have been released during spring training, not even allowed to put on a uniform and play the regular season. There’s a lot of pressure on the players here to do well soon, and I think many, many players that will let go in the first year, if they were given a second year, would blossom. From that same sample, I don’t think it’s changed all that much. I think there’s still that pressure on the players, but I think they’re better scouted, maybe a higher-caliber player. Another thing that’s changed is that it used to be that coming to Japan was like [going to] the graveyard, and players and their agents in the states don’t look at it that way anymore at all, because they know that a player can come here and go back and sometimes even have a great career going back. It used to be that it was the end of the line when you came over here, either a guy that was not going to make it was sure he was not gonna make it in the States so he came over, or the guy was at the very end of his career and came over.

Ray:

Hey, Marty. Thanks to you, we had a great weekend at the park. It was a great weekend and the BayStars automatically became Rakuten fans because they were playing the Hawks. Marty going down to the ballfield in postgame – you and I’ve talked about this in the past – for the audience, what’s your feelings about having a heroes’ interview on the field, when you’re the host team, and your team has just lost the game? The heroes’ interview is actually based on the winning team, which is the visitors.

Marty:

I don’t care for it. If I could make a change, I would get rid of that. There’s a number of things that this Japanese sense of fair play comes into play. In the seventh inning, in the top of the seventh inning, they play the song of the opposing team, they call it the “Lucky Seven.” And I always say “Why are you gonna wish the opponent’s luck? You want them to fail miserably, you don’t want them to have a lucky ending or lucky game.” So that’s again, this concept of fairness but if you see Yamazaki’s film Koshien, with high school baseball, when you lose, you bow, you take off your hat and to honor the other side, and so forth. So there’s a cuteness, there’s a niceness that this is done. But personally, if I made a decision, I want it all to be for my team. I’m not going to want to wish the other team any kind of luck or give them any praise. I don’t really want to do that.

Ray:

Well, again, I thank you for your friendship over the years, and congratulations, Rakuten. Thanks to the BayStars this past week, Rakuten is now in sole possession of first place, because the Hawks are on the down now. So thanks again, Marty, grateful for our friendship, love to the family.

Marty:

Thanks, Ray. Likewise.

Shane:

So that is a wrap! Marty, thanks so much for joining us. Like I said, I’m glad that we were able to do this, it’s been a long time coming. Thanks for your friendship to JapanBall over the years, and thanks for everything you’ve done to promote friendship through baseball. We look forward to continuing to root for the 89ers and seeing what else you got. I’m sure you got plenty more ahead of you and your story – there’s plenty more to it, so I’m really looking forward to that.

Marty:

I look forward to your trips to Japan when you can resume them. I hope it’s soon.

Shane:

Me too. Maybe Ray can sneak us in through the luggage and ship us to the base. Looking forward to seeing you in person, hopefully, and thank you everyone for joining us. Great to see some new faces and some familiar ones. Marty, you got a good crowd here, it’s been trickling down a little bit because the world’s opening back up, but you just kicked our audience participation numbers way back up. So I appreciate that.

Marty:

Well, if anybody couldn’t get their question in, and they want to send me an email, I’ll be happy to answer

Shane:

I’d be happy to put you in touch with Marty, or if you have any questions for me, then please shoot me a note. Thank you everyone.