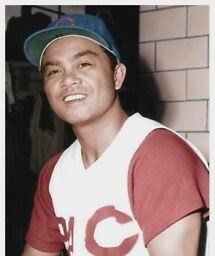

September 16, 1956 marks a significant achievement in baseball history that is so overlooked that it’s not even listed on any of the four “this date in baseball” databases we found online. Collectively, these databases list dozens of unique achievements – many of them seemingly mundane – for each date in the calendar year, dating from the 1800s to present day. But none of them note the day when Bobby Balcena became the first person of Asian descent to play in Major League Baseball, appearing as a center fielder for the Cincinnati Redlegs (now Reds).

Balcena, of Filipino heritage, had only two at-bats in seven big league games, but nevertheless represented the continuation of an important shift in the public mindset that started to gain momentum when Jackie Robinson broke MLB’s color barrier on April 15, 1942: that anyone, no matter their heritage, could play at the highest level.

The fact that few fans recognize this date, or even Balcena’s name, represents an unfortunate reality: the notable markers of Asian American history – the formational events, the notable achievements, and the many instances of acute discrimination – have been underappreciated by the greater American community.

In recognition of May being Asian/Pacific Heritage Month, we felt it important to share more about the legacy of Asian Americans in “America’s Pastime,” using our beloved game as a representation of the greater issue.

Bobby Balcena’s legacy resonates deeply today, as Asian Americans have been at the forefront of some of MLB’s most remarkable recent moments. Fans of the San Francisco Giants will forever remember the heroics of superstar pitcher Tim Lincecum and first baseman Travis Ishikawa. Lincecum – his mother being born to Filipino immigrants – is one of a select group of pitchers to win both multiple Cy Young Awards and World Series championships, and Ishikawa – a fourth-generation Japanese American – was beloved for his clutch hitting, including a walk-off home run that sent the Giants back to the World Series in 2014.

The Giants are not the only team who owe much of their recent success to Asian Americans. Dave Roberts, who was born in Okinawa, Japan, has played a vital role in capturing World Series titles for two iconic franchises. First, there was his epic stolen base that catapulted the Boston Red Sox past the Yankees in the 2004 ALCS. Then, after becoming the first Asian-born MLB manager (and second Asian American manager, after Don Wakamatsu), he led the Los Angeles Dodgers to three World Series in four seasons, capturing the title in 2020.

Catcher Kurt Suzuki– now with the Los Angeles Angels– has endeared himself to the fans of five different MLB organizations over 15 seasons. He is known as a leader behind the plate, the quintessential rugged veteran catcher who contributes with his defense, game-calling, and bat. He played a key role in helping the Washington Nationals to their first championship in 2019.

The list goes on – countless standout American players of Asian descent have populated MLB rosters over the years. You may know that players and coaches with Asian last names like Bruce Chen, Kyle Higashioka, Keston Hiura, Tommy Pham, Lenn Sakata, Don Wakamatsu, and Kolten Wong have Asian ancestry, but did you know that Johnny Damon, Tommy Edman, Jeremy Guthrie, and Christian Yelich do too?

In 2021, there is a chance that a baseball executive of Asian descent played an important role in the construction of your favorite MLB team’s roster. Farhan Zaidi of the San Francisco Giants and Kim Ng of the Miami Marlins lead the baseball operations departments of their respective organizations, and a growing number of clubs employ Asian Americans in scouting, analytics, and player development.

Baseball has long been a favorite pastime of Japanese Americans, going back to the first-generation issei immigrants. For them, baseball was a means to get involved in their new communities, and stay connected with other immigrants. As early as the 1920s, leagues made of Japanese immigrant players arose in the western United States.

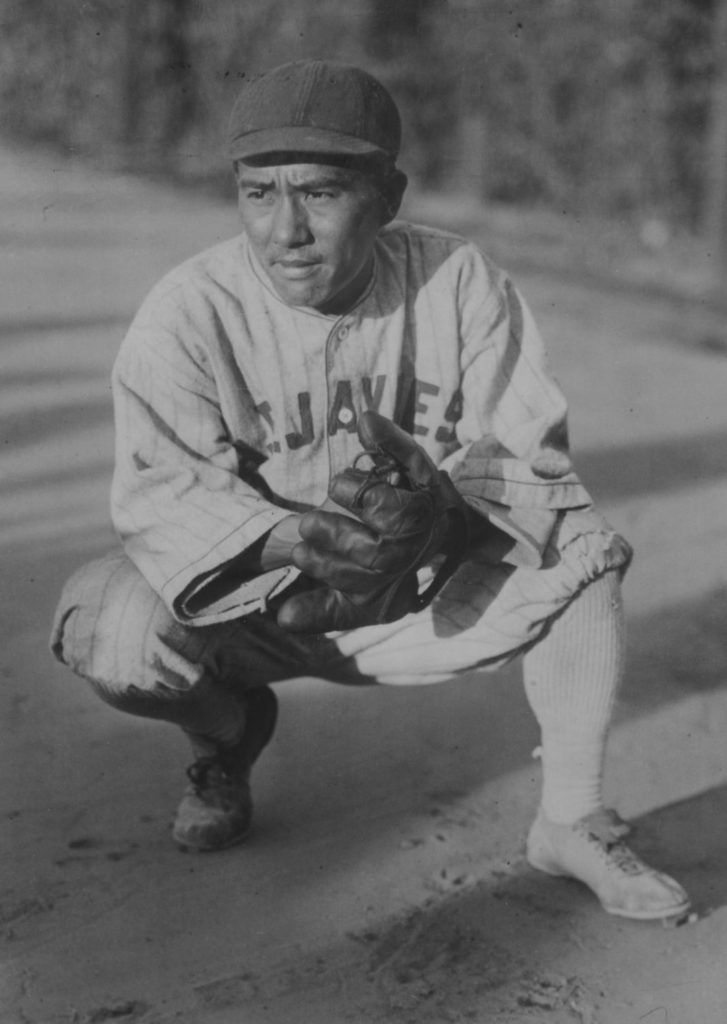

One of the most famous issei players was Kenichi Zenimura, who played all nine positions on the diamond and helped organize teams from his base in Fresno, California. Zenimura, born in Hiroshima, Japan, was a pioneer in the development of Japanese American baseball—he helped organize leagues, games, and even barnstorming tours of Japan, including the Philadelphia Royal Black Giants’ tour of Japan in 1927 and Babe Ruth’s tour of the country in 1934.

“[Zenimura,] as a player, a coach, a manager… broke down barriers in the ‘30s, coaching two all-white teams in an era where Japanese Americans were discriminated a lot against,” baseball historian Kerry Yo Nakagawa explained in an episode of JapanBall’s “Chatter Up!” “Here was Zeni, coaching ‘Al’s Bar’ and ‘James and Company,’ because in Fresno, we had a ‘Twilight League’ where major leaguers in the offseason, and semi-pro players would play.”

Unfortunately for these Americans, many of their neighbors and representative politicians still harbored tension and racist beliefs towards them. When the United States officially entered World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration placed all people of Japanese ancestry living in the U.S. into internment camps, citing concern of domestic terrorism and organized attacks from within the country. Approximately 120,000 people were forced from their homes and incarcerated in concentration camps, most of which were located in remote, inhospitable land. Not a single detainee was ever found to be subersive.

Still in love with the sport, however, Zenimura helped organize leagues while in the camp. The baseball field was an oasis behind barbed wire, a reprieve from the injustice. Many internees credited this athletic diversion – whether as a player or fan – with helping them maintain their physical and mental health. As a result, the sport grew within the Japanese-American community while the war – and racist beliefs – raged on outside.

As long as there have been Asian and Asian-American players playing “America’s Pastime,” there have also been teammates and opposing players making jokes or taunts towards them. Masanori Murakami, the first Japanese-born player, who debuted in 1964 for the Giants, was described in racist terms by contemporary players and newspapers during the entirety of his career, with some calling him an “oriental lefty” and cartoons depicting him as a caricature in samurai armor. While Murakami was embraced by the Giants and their fans – his first start was declared as “Japanese American Day” at Candlestick Park – he still suffered taunts and threats from other members of the community. Based on a belief that Murakami’s ancestors killed Americans in the War, one crazed fan claimed that if Murakami played, he would shoot the manager and anyone who stood in his way.

These threats and jokes have not been limited to a bygone era, as even today’s Asian MLB players suffer racist taunts. In Game 3 of the 2017 World Series, after Astros’ first-baseman Yuli Gurriel hit a home run off Yu Darvish, Gurriel was seen in the dugout pinching his eyes shut and mouthing “Chino,” gestures that led to Gurriel being suspended five games.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues and racially-motivated attacks towards Asians have become more frequent and violent, MLB players have been not been spared from the hostility. On April 21, 2021, in a close game against the Chicago White Sox, Cleveland Indians Taiwanese first-baseman Yu Chang made a throwing error that cost Cleveland the game in the bottom of the ninth. Following the error, Chang was berated on social media with racist comments such as, “you f****n sars corona virus m****r f****r.”

“Instead of learning from our past mistakes in history, we seem to keep repeating them—the names change, but the xenophobia continues on,” Nakagawa further explained. “During the Olympics in China, I remember, my daughter was going to UC Berkeley, and she was saying a lot of the Asians, and especially Chinese Americans, were somehow being singled out because of the tension between China and the US at that point. So now, here we are in 2021… For us to be here at this point in time in 2021, and seeing so much racial tension that with all other Americans – I don’t like to use the word minority, I think all of us are the other Americans – it really pains me to see that history really hasn’t changed; only the names have. I’m hopeful that our grandbabies are going to be in a world that is going to be more progressive and embracing to each other’s humanity…I feel that we all are connected, whether the color of our skin is different, or our faiths are different, we are all are connected by humanity.”

Asian Americans make up 6% of the United States’ population; of 300 million Americans, 18 million of them are of Asian descent. Despite their history, Asian Americans still love their country and think themselves lucky to be part of it in the same manner that any other American would. Noriyuki “Pat” Morita, known for his roles in The Karate Kid and Happy Days, was interned in one of the camps in Gila River, Arizona, and still went on to sing the National Anthem at ballparks and stadiums across the West. According to Nakagawa, when asked why Morita proudly sang the anthem so many times in spite of the injustices he suffered, he replied, “despite what happened to our families, our communities, this is still the greatest country in the world, and that’s why I sing it.”

With all that has occurred recently, it’s more important than ever to recognize the impact Asian Americans have had, not only on baseball, but on the country as a whole. Despite enduring racist attacks and taunts, they continue to work and help move the country in a positive direction: one of shared history, pride, and respect for each other. This continues to be a shared effort, with projects like Nakagawa’s Nisei Baseball Research Project helping to lead the way:

“We’re lobbying to get Major League Baseball to recognize our pre-war American ambassadors that created this bridge across the Pacific, for great players like Murakami-san, Nomo-san, Ichiro-san, Matsui-san, Matsuzaka-san, to raise the bar even higher,” Nakagawa said. “To think about our great players that were considered too small for Major League Baseball, but nobody says that about Jose Altuve or Dustin Pedroia, even though they’re small players, but they become MVPs in Major League Baseball. We’re hoping that much like the pride and the passion for the Negro Leagues that is permanent at Cooperstown, much like the All-American Girls [exhibit] that’s permanent, [and the] Latinos in Baseball [exhibit], we’re hoping that Japanese Americans and Japanese Nationals that played baseball here, will be recognized with a permanent exhibit… we’re hoping through the prism of baseball, to have these touchstones, artifacts of history, of our legacy and players, so that we can educate more people on every coast and around the world, and to let them know that our issei and nisei (second generation) ballplayers, many of the players today in Major League Baseball, they’re standing on the shoulders of those early issei and nisei that risked and crusaded and had so much great travel on ships to go to Japan, to Korea, to Manchuria, China, just to be ambassadors for our game.”

The impact Asian Americans have had on baseball should not be understated. We relish the opportunity to share their history – the notable achievements along with the ugly discrimination; a history filled with remarkable ability and resilience. We at JapanBall are proud to acknowledge and celebrate the history of Asian American ballplayers, and encourage all those who love the game to do the same.