Hall-of-Fame catcher Ted Simmons said he was perhaps the best pitcher he’d ever faced. American NPB star and long-time teammate Leron Lee said he was the best pitcher he’d seen except for Bob Gibson. Certainly, he was one of the best pitchers many Americans have never heard of.

“He” is Choji Murata, the Japanese Baseball Hall-of-Famer who passed away in a fire at his home in Tokyo on November 11, just short of his 73rd birthday.

He is unfamiliar to the majority of Americans because his career ended in 1990, five years before Hideo Nomo started to direct American baseball fans’ attention across the Pacific. But he is no stranger to former teammates and opponents, and fans of the Japanese game.

“When Choji was on the mound, it was time [for opponents] to take a holiday.”

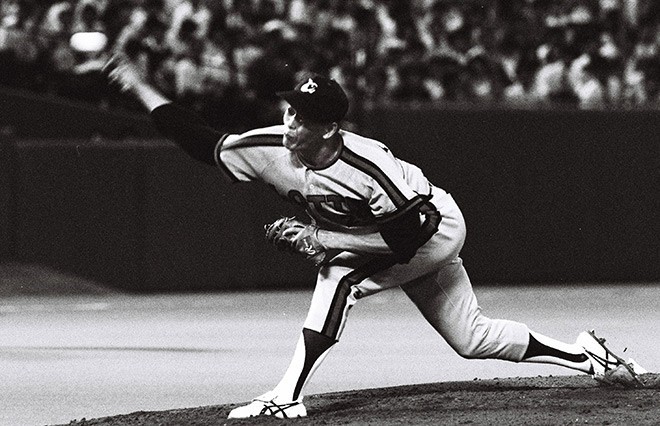

The externals of Murata’s career are thus – he won 215 games over 22 seasons with the Lotte (née Tokyo) Orions (now the Chiba Lotte Marines). He was once a 20-game winner, three times the Pacific League ERA leader, author of five one-hitters, pitcher in a 10-inning complete game that clinched Lotte’s only Japan Series title (1974), a 12-time all-star, and possessor of a mid-90s fastball and a forkball that seemed to drop off the face of the earth. But those are just bare facts. For the story, one must turn to contemporaries such as Leron Lee and his brother Leon, Murata’s teammates for 11 and five seasons, respectively.

“I played with him, not against him – luckily,” Leon said. “The only time I would face him was in intra-squad games early in spring training when it was still really cold. No one wanted to face him then, so we’d let the rookies go against him. He had this fastball that could get up to 96 (MPH) and often ran in on righthanded hitters, as well as a devastating forkball. No disrespect toward guys like Nomo, but Murata was way more powerful. Had he come to the U.S., he would have had much more success than any others that came over.”

Leron added, “If he had been on one of the strong teams when he played, I think he would have won 400 games. I’m very happy that I was on the same team with him. Otherwise, my lifetime batting average would have been a lot lower. Murata could easily have pitched in the majors and probably would have won 20 games a year. Other pitchers who came over were no comparison to him.

“Here’s the best way to sum him up as a pitcher,” Leron continued. “Ted Simmons was a teammate of mine and is still a really good friend. He faced Murata during an all-star series [following the 1979 season], and said he was probably the best he’d ever faced, with his four-seamer and forkball. And he had a good cutter, too.”

With a high leg kick, overpowering stuff, and a legendary arm, Choji Murata might remind some American fans of Nolan Ryan. Like Ryan, Murata had a unique delivery – a “really funky windup with a high kick”, according to Leron – that enabled him to hide the ball well:

Both Lees clearly remember an incident in the late 1970s when a hard inside fastball from Murata broke the hitter’s bat in half, hit him on the back leg, and ricocheted back into the field of play.

“Oh, yes,” Leon recalled. “We were playing the Seibu Lions up in Sendai, and Choji was really on fire that day. I was playing first base and was able to see it clearly since the batter was righthanded. No one really understood at first what happened. The batter stayed in the box, and the umpires weren’t sure. I tagged the runner, just in case, but they finally ruled it correctly as a foul ball. But I’ve never seen a ball thrown so hard. I don’t think any major-leaguer would have been able to hit it.”

Leron added, “It was unbelievable for a ball to go through a bat and still have enough momentum to then hit the batter and still roll forward.”

Once, a television station dressed up someone in a samurai suit with all the traditional armor. The idea was to show how it felt to get hit with a Murata fastball.

“The guy got in the box, and Choji was going to hit him in the arm where some heavy armor was, but the batter jumped out of the way every time,” Leron said. “Even with the armor, he was still scared to get hit. I think a lot of guys felt that way when they batted against him.”

Marty Kuehnert, the first foreigner to be general manager of an NPB team (the Rakuten Golden Eagles), was a broadcaster in the mid-1970s and saw Murata at his peak.

“The Hankyu Braves were a really great team then,” Kuehnert said. “They won the Japan Series three years in a row (1975-77), and the only team they really feared then was Lotte when Murata was pitching. He got a lot of respect because of how tough he was.”

With a chuckle, Leon Lee added that “Some veterans on other clubs would take days off when he was pitching. His forkball was really hard to pick up. When Choji was on the mound, it was time [for opponents] to take a holiday.”

His own catchers probably wished for strategic days off, as well. They suffered numerous passed balls, and, perhaps surprisingly, Murata led his league in wild pitches 12 times and set a Nippon Professional Baseball record with 17 in 1990. But there was good reason.

American Boomer Wells, who played in Japan for ten seasons, said in Robert K. Fitts’ Remembering Japanese Baseball: An Oral History of the Game, “I didn’t know this until the end of my career, but [Murata’s] catcher never gave him a sign. Murata just threw whatever he wanted, and the catcher had to just see the ball and catch it. No wonder he had so many passed balls. This man was throwing 95-97 miles per hour with an awesome forkball and a devastating slider, and his catcher didn’t know what was coming. I had wondered why Murata would pitch so quickly. He would just get the ball and throw.”

More than 10 years after he left the game, Murata played in an exhibition against retired American players and struck out all six batters he faced with a fastball reaching into the low 80s. At the age of 63, he threw out the honorary first pitch before a game, and it was measured at just under 84 miles per hour:

“The last time I saw him was in an exhibition – I guess in the late ‘90s or early 2000s – and I got a hit off him,” Leron said. “I was told that I was the only foreigner to do that in those games.”

Kuehnert added that Murata would play in an old-timers game each year at the Tokyo Dome and “was throwing faster than some of the young pitchers.”

Better than the Numbers Suggest

Interestingly, his statistics – while obviously good – don’t necessarily stand out as much as one might expect. For his career, Murata had an ERA of 3.24, a .548 winning percentage, and a 1.25 WHIP. He allowed averages of 8.2 hits and 3.1 walks per nine innings. He was a 20-game winner only once and had double-digit victory totals just 10 times in his 22 seasons. He averaged 6.1 strikeouts per nine innings, lower than one might expect for a pitcher with his type of stuff.

There are at least a couple reasons for this. The relatively low strikeout average is in part because the Japanese hitters are excellent at fouling pitches off – they actually practice that – and avoiding strikeouts.

Leron remembers “a fellow playing for Kintetsu [a predecessor of today’s Orix Buffaloes] – I can’t remember his name, but he batted almost 600 times one season and only struck out something like three times. They make contact and put the ball in play. They usually aren’t powerful hitters, but they’re good hitters.”

“Hitters in Japan are much more disciplined than in the U.S.,” Leon concurred, “and Choji threw a lot of strikes that opposing hitters put in play. If he was pitching over here [in the U.S.] today, he’d strike out twice as many. With the focus here on upper-cutting and launch angle, he would have gotten a lot more swings and misses.”

In addition, Murata was overworked, and his trademark toughness may sometimes have worked against him. The Japanese tradition has been to have pitchers throw hundreds of pitches before, during, and between games From his time playing in Japan, former pitcher Kevin Beirne remembers when ace Daisuke Matsuzaka threw a 365-pitch bullpen session. The approach today is a bit more protective of pitchers’ arms, but in Murata’s time, it was pretty much a case of keep-throwing-unless-your-arm-falls-off. On his off-days, Murata would throw 100 or more pitches in practice.

Further, though an elite starter, Murata also was a relief pitcher! He made 433 starts and 171 relief appearances during his career. The year 1976, when he won 21 games, is a good example of his heavy workload: he made 24 starts, completing 18, and entered a game as a reliever 22 times.

“They didn’t use him correctly,” Leon said. “There should have been more consistency between starting and relieving. They sometimes pitched him past his time. He might pitch a complete game and then relieve a day or two later and not be as effective. And he was sometimes his own worst enemy, too. He was really into the concept of the fighting spirit, priding himself on putting every bit of effort into every pitch. He pitched past when he should have, especially as he got older.”

Leron said he would always go to the ballpark early to see who was pitching in the bullpen. He would count the number of pitches and see how long they threw. “Then, if he pitched that day or the next, I’d know that his fastball wouldn’t be normal. It was the same with Nomo. I did a scouting report on him before he came to America. His arm was in bad shape [Indeed, he pitched just 114 innings the year before signing with the Los Angeles Dodgers after four seasons in excess of 200], but when he got to America, they changed all that and he was in very good shape and did very well.”

Snakeskin, Icy Waterfalls, and Hot Wax

Murata started having serious elbow problems in 1982 and appeared in only six games that season. When the team doctor said he couldn’t find anything wrong, Murata decided to work his way through the pain and continued throwing. Against the advice of some, including his wife and Leron Lee, he threw a ball against a wall every day to try to pitch through the injury, but the problems did not get any better, and he got to the point where he couldn’t raise his arm above his shoulder.

“His elbow would swell to two or three times its normal size,” Kuehnert said. “Like bubbles.”

Leron Lee said, “I saw him one time being worked on, and his arm looked like it had been run over by a train – yet he was still doing long toss.”

Leon added that “He was constantly in the training room, and he tried all kinds of concoctions on his arm. They’d put oil on it and then wrap it in snakeskin. The next time it would be hot wax. It had to hurt like crazy. Talk about a samurai spirit – he was really into that. No one pitches today with an arm like that.”

Robert Whiting – author of multiple books about baseball in Japan – wrote that Murata “practiced Zen, meditating in a forest temple on the Izu Peninsula in the coldest part of winter, standing semi-naked under an icy waterfall. A Zen master named Takamatsu gave Murata massages and wrapped his arm in a snakeskin that had been soaked in shochu ‘to draw out the poison.’ But again, nothing worked.”

According to Baseball Reference, A Japanese American fan sent a letter to Murata advising Tommy John surgery, and his wife encouraged this, but Murata kept trying different medical centers. All the doctors told him “there is nothing wrong with your arm.” Through it all, Murata continued to try to pitch. When a Lotte club official told him to rest, he said “a man should pitch until his arm falls off.”

The team finally barred him from pitching.

Murata became depressed, and the media wrote him off as washed-up. He even told his wife that she was free to leave him, as he had promised that the marriage could end when he was no longer the best pitcher in Japan. His wife, though, refused to leave, and she was a big factor in Murata finally going to see Dr. Frank Jobe in Los Angeles. Jobe diagnosed a severed tendon and eventually performed his revolutionary Tommy John procedure. Murata was the first prominent Japanese player to have the surgery.

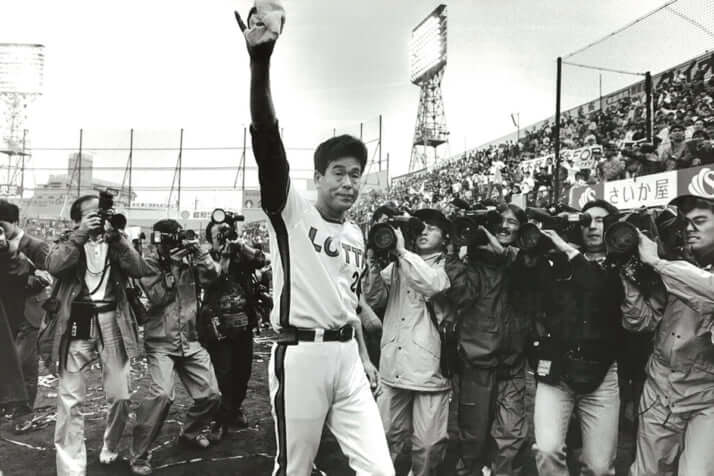

Murata missed most of the 1982 season, all of 1983, and nearly all of 1984 before returning, 1,070 days after his last appearance. Dr. Jobe told Murata not to pitch as frequently, that he should rest six days between games and not throw 100 pitches a day between games as before, and Murata heeded the advice. In the nine full seasons prior to the injury, he had averaged 37 games and 212 innings. In his last six full seasons, he averaged 22 games and 150 innings, and he made only seven relief appearances, all in his final year.

Due to age – he was 35 when he came back after the surgery – and the previous toll on his arm, he wasn’t the same pitcher afterward. He did go 17-5 in 1985 and win the Comeback Player of the Year Award, but while his earned-run average pre-surgery had been 3.01, it was 3.86 after.

“But he was effective enough to help the club,” said Leron, who played for the Orions through the 1987 season. Murata retired following the 1990 campaign.

His comeback convinced some other Japanese players to undergo surgery, though Murata had mixed feelings about it. He criticized some of these players for choosing surgery too quickly instead of trying to fight through it, showing he still harbored some traditional beliefs. Whiting wrote that “It was a trend that he viewed with some suspicion, in that he believed going under the knife made a comeback too easy. ‘Suffering is what built character,’ he liked to say.”

On the other hand, following the first season of his comeback, Whiting says that Murata and his wife flew to Los Angeles to personally thank Dr. Jobe. Murata also tried to discourage young teammates from throwing as often in practice, but he said, “they ignored me. They still think pitching hard every day is the only way to success. Some things are hard to change.”

A Retired Baseball Ambassador’s Awful Final Year

After retiring, Murata worked as a commentator for the Japanese television network NHK, then became a coach for the Daiei Hawks for a time. He also promoted baseball among children by coaching teams and holding tournaments, particularly on remote islands.

In September this year, just two months before dying from a fire in his Tokyo home, Murata was arrested at Tokyo’s Haneda airport for an alleged assault on a female security officer. Allegedly, he was upset for being stopped after going through a metal detector with his mobile phone. Murata allegedly shoved the inspector’s left shoulder with his right hand. He initially denied the charge by claiming he never touched the woman’s shoulder. Murata later apologized, and the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department’s airport division said it would continue investigating the incident.

“That just seemed so out of character for Choji,” Leon said. “He was very calm, quiet, easy-going. He never showed anger. But you never know what might have been going on. Some of his sponsors had dropped him, and maybe that was affecting him.”

Leron agreed, saying, “I never saw him in a bad mood, even when he lost a game. When I heard about the episode at the airport, it didn’t sound like the person I had known and played with for 11 years. For him to push a lady down and to say some of the things they say he said – that’s just not like Choji.

“I also talked to Bob Whiting, and he said the same thing – that it didn’t sound like him. I just remember what a great pitcher and great person he was.”