There’s no doubt that Black ballplayers had a large impact on the origins of Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB). From the barnstorming tours of the Philadelphia Royal Giants, to Jimmy Bonner, the first player to break the color barrier against Blacks, Negro League All-Stars were instrumental to the development of professional baseball in Japan, demonstrating to Japanese ballplayers that a higher level of play was within reach.

Nearly ten years later, however, the environment was completely different. After the events of World War II, NPB (known as the Japanese Professional Baseball League until 1949) became a largely internal league, depending on national talent and developing teams from local hotspots like Hiroshima. Japanese baseball, despite growing from international interactions, was an isolated sport.

With tensions high and the need for goodwill higher, Black ballplayers once again helped develop a shared passion for the game they loved, and eventually, build up an international bridge on the sport, the likes of which have never been seen anywhere else. Who were these players, however? Who helped them get back into Japan? And how did the relationship develop from there?

Once again in the effort to recognize the legacy of forgotten stars and their role in professional baseball, JapanBall will attempt to answer these questions, and help share another side of history. With the continued aid of baseball historian Bill Staples, Jr., we’ll continue to share their stories and highlight the impact of their contributions, even in the modern game.

But to start, we’ll need to start in a completely different sport: basketball.

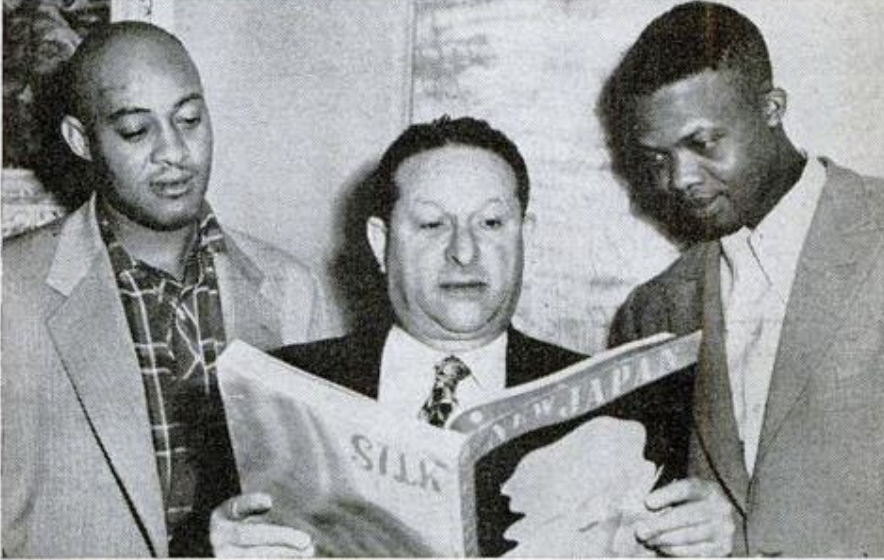

Abe Saperstein, Bill Veeck, and the Growth of Black Sports

Although he’s better known for his work in basketball, Abe Saperstein is one of the more critical figures in Negro League history, serving as a prominent team owner, league promoter, and player agent; these roles would eventually lead to him negotiating some of the most important deals in baseball history, including the first-ever lending of Major League Baseball (MLB) players to NPB: Jimmie Newberry, and John Britton

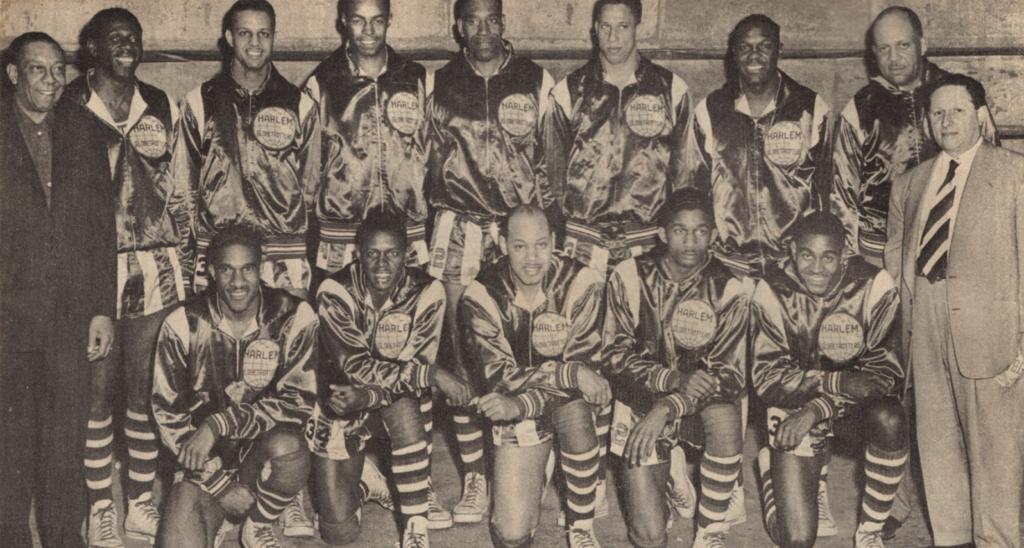

Saperstein got his start in promoting when he founded and coached the Harlem Globetrotters in 1926. While the team is now known for their acrobatic performances, the Globetrotters played a critical role in integrating basketball, being one of the first true professional Black basketball teams. Playing in different gyms across the Midwest, hundreds of people would come to see the athletes’ trick passes and slam dunks against local teams– games the Globetrotters were almost guaranteed to win, as the team emerged triumphant in 100 of their first 105 games. Later on, the Globetrotters became big enough to take on the reigning Basketball Association of America (a precursor to the modern National Basketball Association) champion Minneapolis Lakers; a game they would win in the final seconds.

The team’s success, in turn, made Saperstein a huge success in the sporting world; the Globetrotters were not only making the sport more popular, but becoming a promotional phenomenon, traveling across the States and even into Canada. As the team traveled and booked increasingly more venues, Saperstein became more involved in the promotion of other sporting ventures, including the Negro Leagues.

Building contacts and connections as the team traveled, Saperstein had an important (albeit not without controversy) mark on the Negro Leagues. He booked legendary Satchel Paige on various teams across the states, helped publicize the Negro Leagues East-West All-Star game, and purchased shares in the Birmingham Black Barons, one of the most legendary teams in Negro League history. Saperstein was a superstar in the sporting world, and the connections just kept getting bigger.

Two of those connections were Black Barons manager Winfield Welch, who is commonly recognized as one of the greatest managers in Negro League history and began his work with Saperstein coaching the Globetrotters, and the always-influential, sometimes-controversial baseball renaissance man Bill Veeck. Over dinner one night, as the two men watched Veeck’s Cleveland Indians get destroyed by the Detroit Tigers, Veeck mentioned that Paige could give a better pitching performance; one quick workout later, a contract was drawn up.

It should be noted that while Saperstein and Veeck were critical members of their sports and promoting an integrated game, they were also businessmen looking for opportunities for easy money…even if that meant exploitation. While Saperstein was able to get the Black Barons into places like Yankee Stadium, he was also criticized by some owners for his promotion of teams like the “Zulu Cannibal Giants,” who would play baseball in grass skirts and perform comedic acts between innings. Veeck also does not escape exploitation claims, as the infamous 1951 “Eddie Gaedel” game shows. Gaedel, standing at 3-foot-7, entered a St. Louis Browns game with the hope of attracting leering fans into the stands; while Gaedel got on base and has his “⅛” jersey displayed in the Cardinal Hall of Fame, it was an example of Veeck exploiting a marginalized group, even derogatorily calling Gaedel a “midget” in his autobiography.

As promoters, however, the two men were often searching for new opportunities, and soon turned their eyes towards Japan. Veeck, now owner of the St. Louis Browns, was often seen scouting Japanese players in Hawaii, and Saperstein was trying to formulate a plan to take the Globetrotters international. Their work eventually brought them to Umeichi “Mackay” Yanagisawa, who worked with Saperstein to bring the Globetrotters to Japan. Keeping their eyes open for opportunity, they soon found one: sending minor league players to NPB.

The First “Lent” Players in Japanese Baseball

The Hankyu Braves (now the Orix Buffaloes) were looking for new talent to help them break out of their mediocrity. With Wally Yonamine of Hawaii beginning his fantastic career for the Yomiuri Giants, the Braves began to look stateside for new talent, and found an offer from Veeck and Saperstein. Veeck, excited for the press opportunity, promised the Braves two former Negro League stars: third baseman John Britton, and pitcher Jimmie Newberry. The deal was completed April 14, 1952- the very day Japan was liberated from Allied control. Saperstein made the final arrangements for the two, and they left for Japan to become the first lent Major League players.

“As Japan gains its independence as the world’s newest democracy, we of the St. Louis Browns are happy to aid the mutual relations between the United States and Japan by sending two of our American ball players to the Japanese pro leagues,” Veeck told the Associated Press in announcing the deal. “In Japan, as well as in America, baseball is the national game, and we feel that this gesture on the part of American baseball will go a long way toward cementing good relations with the Japanese.”

Who were these players, exactly? Britton was an infielder who played for Saperstein’s Ethiopian Clowns and Birmingham Black Barons, and was a critical hitter for both teams, helping the Barons win the 1944 and 1948 Negro American League pennants. Newberry also played for the Black Barons, going 14-5 with a 2.18 ERA in 1948, and also saw time in the Manitoba-Dakota League. After the integration of Major League Baseball, as well as the continuing conversations between Veeck and Saperstein, Britton and Newberry both signed with the Browns in 1952, who promptly flipped their contracts over to NPB’s Braves.

In the 1952 season, both Britton and Newberry saw fantastic success in Japan. Facilitating their success was Hall of Fame manager Shinji Hamazaki, who had seen and played against the Royal Giants during their 1927 barnstorming tour. The two performed as promised: Britton was seventh in the Pacific League with a .316 batting average, only striking out 12 times. Newberry also saw success, as after he made the adjustments that had doomed Bonner (control, smaller strike zone), he went 11-10 with a 3.23 ERA over 206.1 innings. What’s more, the two were very popular among Braves fans; at the end of the season, 1,000 fans came to say goodbye as the two left to return to the States.

A bridge had been built, and in 1953, Britton returned to the Braves with two more former Negro League stars: Larry Raines and Jonas Gaines. Raines, still young and hungry for a contract, would win a Pacific League batting title in 1954 with a .337 average and 96 RBI, while Gaines would post a stellar campaign in 1953, posting a 14-9 record with a 2.53 ERA. The trio helped Hankyu finish second in the Pacific League in 1953, just four games behind the Nankai Hawks.

The former Negro Leaguers had completed almost everything anyone could have wanted from the deal: Britton and Newberry brought life to a slumping team. Foreign talent once again had a role in Japan, and the fans were loving it. Saperstein had booked a Japanese tour for his Globetrotters, and had become so popular for negotiating the deal, that after helping the Braves land Raines in ‘54, he was presented with a silver platter by Braves’ Vice President Minoru Murakami, with the team name and all players’ initials engraved.

Beyond the Braves:

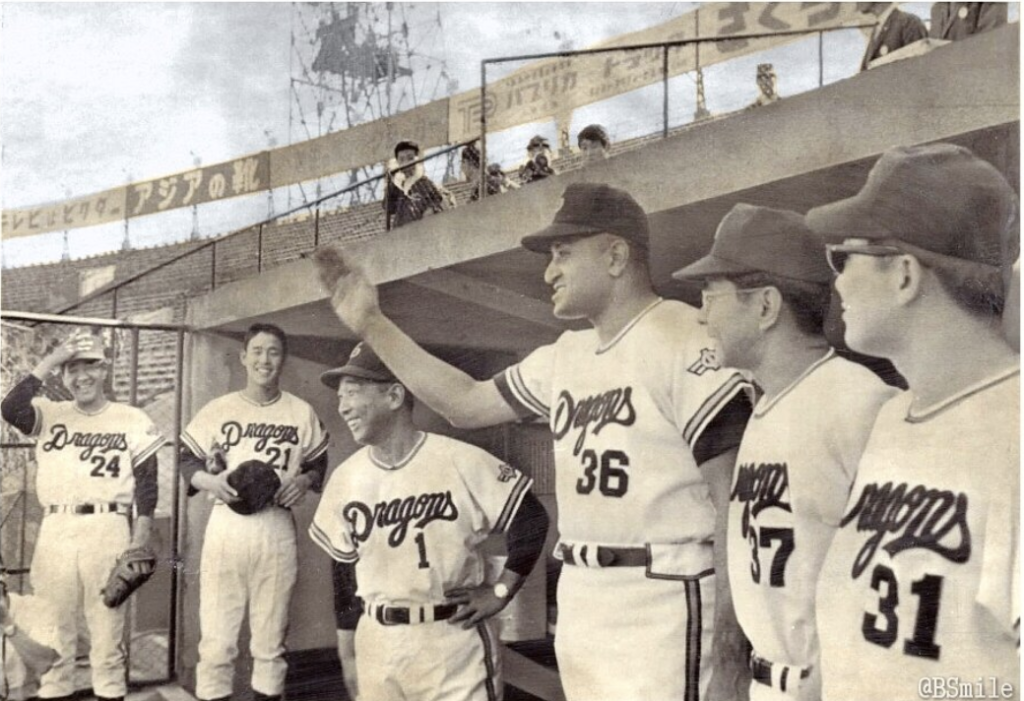

Veeck’s statement about building goodwill in Japan had come to fruition, and more teams and players began to tour Japan, engaging new audiences and continuing to build the bridge between the two former feuding nations. As more players began to enter Japan to try their hand and earn more cash, it even became a matter of U.S. security, as evidenced by the short but notable Japanese careers of former MLB stars Larry Doby, who had broken the American League color barrier with the Cleveland Indians, and Don Newcombe, who had won the MVP and Cy Young in 1956 with the Los Angeles Ddogers.

Doby recollected that the Chunichi Dragons had approached him with the opportunity to play in Japan in 1962, and when he agreed, he received a call from Pierre Salinger, President John F. Kennedy’s press secretary, to meet with the President at the White House to discuss the opportunity. Salinger told Doby that the Japan-U.S. relationship was strengthening, and through baseball, they could develop even further. Doby and Newcombe only played a single season for the Dragons, with Doby batting .225 and Newcombe only appearing in one recorded game, but it continued to build the bridge; more and more stars were coming to play in Japan.

Those stars included pitcher Joe Stanka, who won 26 games for the Hawks in 1964 and became the first American to win the Pacific League MVP, and pitcher Gene Bacque, who that same year won 29 games with a 1.89 ERA and became the first American to win the Eiji Sawamura Award for the league’s outstanding pitcher. On the other side of the spectrum, young pitcher Masanori Murakami became the first Japanese player to play in MLB when the Hawks lent him to the San Francisco Giants; Murakami would go on to be a young stud for the Giants, striking out over a batter per inning, on average.

Although Murakami would be the only Japanese player to play in MLB until Hideo Nomo’s famous departure from the Kintetsu Buffaloes in 1995, there was no doubt that Japan and the United States were back on the same page. The bridge was rebuilt, and the two countries were sharing their love for the game. Because of the fantastic play and efforts of former Negro Leaguers like Britton, Newberry, Gaines, and Raines, goodwill had been established and a new love of the sport was found.

It only went up from there.

Epilogue:

Since the Royal Giants’ tour in 1927 and the creation of the Japanese Professional Baseball League in 1935, there have been more than 600 American players in Japan, with several Black ballplayers continuing to play key roles in the league’s history. Legendary slugger Tuffy Rhodes ranks third all-time in career home runs; Clarence Jones was the first foreign player to win a home run title in NPB, with 36 in 1976; Leron Lee held the highest batting average in Japanese history (minimum 4000 ABs) until 2018; and so many more hold places in both the record books and the hearts of fans across the league.

Simply put, there’s no understating the amount of impact Black ballplayers have had on the Japanese game. With the help of Japanese-Americans like Kenichi Zenimura and Harry Kono (mentioned in Part I), the two groups have shaped an international sporting bridge unlike any other, creating an amazing relationship between the two countries and a legacy that should not be lost to time. Black ballplayers like Mackey, Rogan, Dixon, Bonner, Britton, Newberry and more, should be recognized beyond their play; they blazed trails, encouraged growth, and created new opportunities along the way.

On behalf of all fans of the Japanese game, we say “thank you” to these pioneers. For everything.