For the foreigner playing baseball overseas, there are inevitable contradictions – the appeal of the new and the longing for the familiar; the tasks made easy and the tasks that frustrate; some things understandable and others clear as mud. And a game that looks the same as the one back home – until it doesn’t.

Leon Lee knows this as well as anyone.

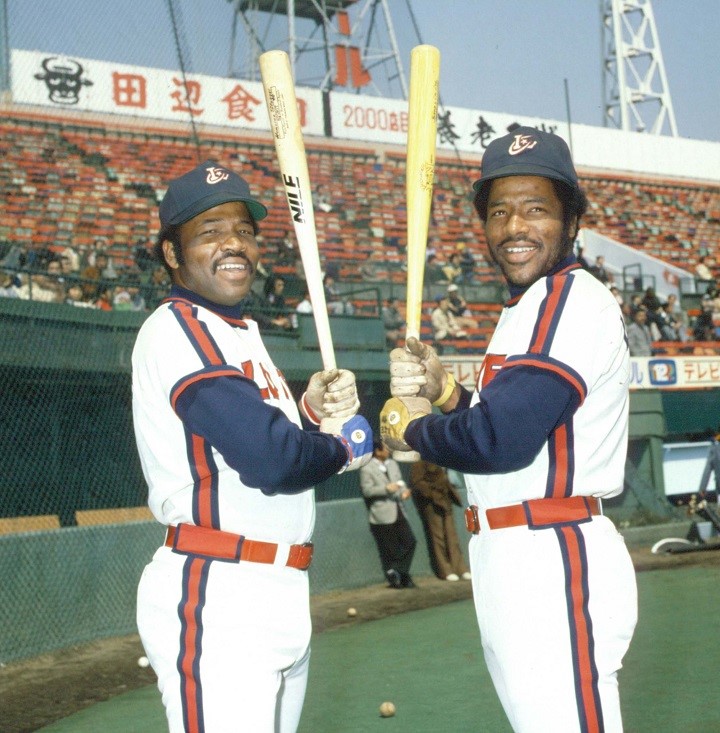

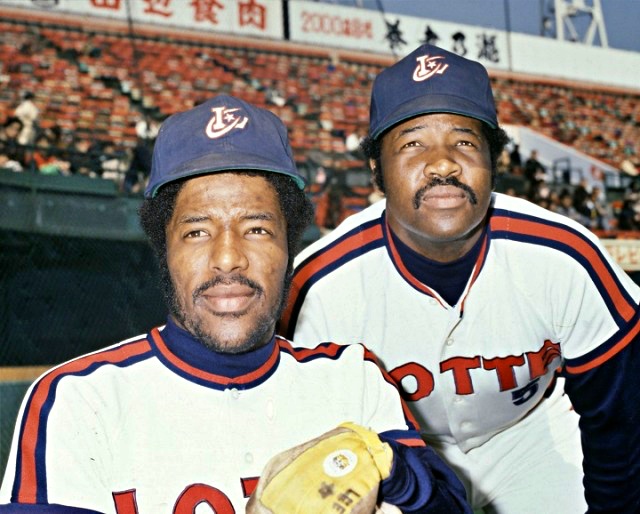

Lee spent ten seasons in Japan and experienced the highs and the lows. On the one hand, he played a starring role, made good money, played on the same team as his brother Leron for five seasons, and had the opportunity to fully experience a new culture. On the other, as a foreigner – a gaijin – he always felt somewhat like an outsider in a famously insular society. He and Leron had stellar careers and set some records but rarely got the recognition that their successes merited.

It was, it might be said, a well-rounded experience. And, overall, certainly a positive one.

Leon, who now lives in his native Sacramento, California, says, “There were things there that made it tough, but there were a lot of good experiences and certainly more positives than negatives about my time there.”

A League of Brotherly Love

Along with his brother, he became a fan-favorite with the Lotte Orions (now Chiba Lotte Marines). The two thoroughly took advantage of their time abroad, indulging in the delicious and exotic Japanese cuisine and learning to speak Japanese. Leron even eventually married a Japanese woman.

Leon found Japanese culture to his liking in many respects. He liked how society was organized, and the country was safe and clean. He made friends in Japan and found the people to be courteous and the service top-notch. “I had a car, and people would take it and wash, clean, and gas it up and then return it. You won’t find that in the U.S.”

And it was there that he was accepted as a player after not advancing higher than AAA in the U.S.

“When I go home [to California],” he said then, “nobody knows what I’ve done. If I’ve had a great year, people say, ‘Well, it’s because the fences are short. He couldn’t make it here, so he made it in the Slow League.’”

At various points while playing in Japan, Leon received offers from MLB teams such as the San Diego Padres and San Francisco Giants, but neither was to his liking because they were simply invitations to spring training as a non-roster player; there were no guarantees. “I went to Japan with a grudge because I really felt I should have been in the major leagues,” he said, “but it all happened for a reason. I got a great education, and it opened a lot of doors for me.”

He got along with his teammates, saying that “Once they see you make an adjustment to their culture, then another guy will say, ‘Why don’t you come out with me tonight?’”

One teammate, long-time Yokohama infielder Daisuke Yamashita, became a mentor to Lee’s then-10-year-old son Derrek, who became a 15-year major leaguer and All-Star, Gold-Glove winner, and batting champion.

“Daisuke was very kind to Derrek,” Lee said. “He kind of took him under his wing. In fact, Daisuke and I were on a program together last year on NHK [the Japan public broadcaster]. That was fun.”

While foreign players have had issues with Japanese managers – and the Lee brothers were no exception – Leon speaks highly of his first manager there, Lotte’s Masaichi Kaneda.

“He said I had ‘soft eyes,’ so I could play in Japan,” Lee said with a laugh. “He was tough on me; I lost 22 pounds in the first spring training because he made me run so much. But he looked after us and would really protect us. It may have been in part because he had some Korean heritage, so he hadn’t been accepted at first, either. I remember one game when the weather was bad and we were getting badly beaten. Before the game was over, he gave us some money and told us to go get a steak dinner – that we didn’t have to sit through a game like that.”

Leon remembers many nights after games when import players would gather at famed pizza restaurant Nicola’s, founded in the mid-1950s by an American soldier who was part of the occupation forces following World War II. “You’d see some Yakuza [Japanese organized crime] guys in there sometimes, as well as other celebrity types. We were called the ‘Godfathers of the Gaijin Syndicate,’” he laughed. “Guys who came over to play there would call us to get insights on what to expect.”

In 1980, the brothers recorded a children’s song called “Baseball Boogie” that rose to the 12th spot on the Japanese charts. Leon says they wrote the song while sitting on a train that had been halted because of a snowstorm. It sold well – “They even had it in the karaoke bars” – and further solidified their standing with fans, who would sing it each time they came to bat.

Leron, who was once voted “Mr. Orion” in a season-ending poll of Lotte fans, says, “the fans were fabulous. One of the greatest stories was from a time in Osaka Stadium. I was in right field, and our outfield coach was telling me to move over toward the line because the right-handed hitter at the plate tended to hit to the opposite field. I did, but one of the fans kept telling me to move over even more. The coach kept telling me to stop, but I kept going until I was almost to the line. Then the guy hit the ball right down the line and right into my glove. That fan knew what he was talking about.”

Leon now reminisces, “The fans were great to us.” A lot of times we’d put on our uniforms at the hotel and walk through the lobby to our bus. People would be waiting for us, and we’d greet them and sign autographs.”

Don Baylor, an MLB All-Star and manager, traveled with Leon during a tour of Japan following the 1990 season. He recalled how the fans cheered for Lee while clearly disliking Bob Horner, the American star who had put up good numbers in his one season (1987) in Japan but turned down a lucrative contract extension and then criticized the Japanese game in published comments.

“They called Horner the ‘Ugly American,’” Baylor said. “But Leon was the import, the gaijin, who accepted their culture. He had all the clout and knew all the people. They love him here.”

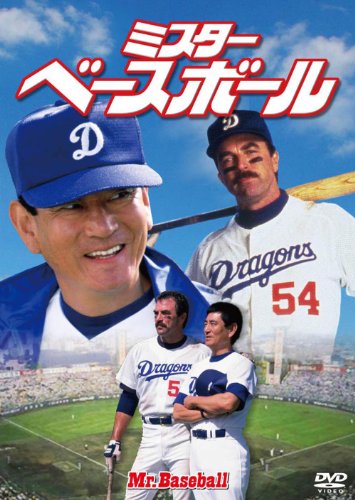

Lee’s familiarity with Japan and the Japanese game there led to him being hired to work on the 1992 movie Mr. Baseball, starring Tom Selleck and Dennis Haysbert. He selected most of the extras and was heavily involved with the cameras, continuity, storyboards, and more. He, Selleck, and Haysbert had dinner together several times a week for four-to-five months and became good friends.

Still, things weren’t always wonderful, despite his and Leron’s success on the field.

The Unique Challenges of Being a Standout NPB Import Player

Leron arrived in Japan in 1977 after playing for four major-league teams over eight seasons. Leon followed the next season after his brother made a concerted effort to convince Kaneda, the team’s manager, to offer Leon a deal. Both immediately made large impacts on the field.

In his first season with Lotte, Leron batted .317, hit 34 home runs, drove in 109 runs, and posted a .978 OPS. He led the Pacific League in home runs and RBI that year and was named an All-Star for the first of an eventual four times. His best year was 1980 when he led the league in batting with a .358 mark. In 11 seasons with the Orions, Leron hit 283 home runs, had a .924 OPS, and batted .320 – the highest career mark in NPB history among players with 4,000 or more at-bats.

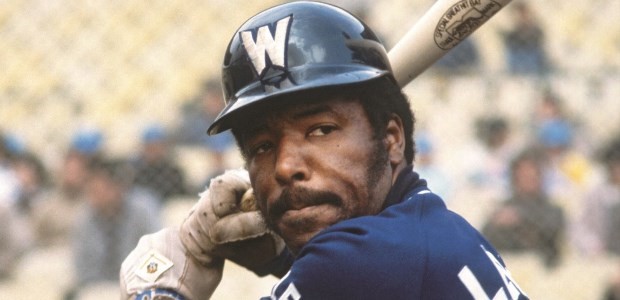

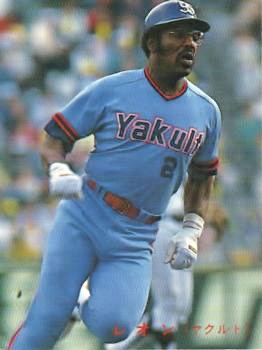

In 1978, Leon’s first year with Lotte, he made sure to prove that Leron’s recommendation was not just a case of nepotism – he batted .316 and never stopped raking, hitting .300 or better in eight of his 10 NPB seasons (he also played for the Taiyo Whales and Yakult Swallows). His best season statistically was 1980, when he hit .340 with 41 home runs, 116 RBI, and a 1.039 OPS. For his career, he hit 268 home runs, had a slash line of .308/.372/.530, and only struck out an average of once every eight at-bats. He twice earned “Best Nine” (the top players at each position as voted by a panel of sportswriters).

The two hold the second-highest professional baseball home-run total for a brother duo (551), topped only by Hank and Tommie Aaron (the DiMaggio brothers hit 573, but there were three of them – Joe, Vince, and Dominic). Pretty impressive company, especially considering that the NPB regular season was just 130 games.

The brothers produced these impressive numbers despite facing unique challenges as import players, an existence that Leon acknowledges “was frustrating.” For example:

- “The strike zone for us would be much wider than for Japanese players,” said Leon. “I once talked about that with an umpire that I liked, and he told me there has to be a balance with everything in Japan, so they thought we had to have a bigger strike zone so we wouldn’t hit 80 home runs a year. Getting a fast ball down the middle would shock you. I once told my manager to ask the umpires about it, and he just smiled and said I should get a longer bat…It kept us from showing our true abilities. The year I hit 41 home runs I could have hit 60. In a way, it was kind of flattering, but it was frustrating that we were viewed as kind of a threat when our intent was simply to do what we could to help the team.”

- Leon recalls times when balls he thinks should have been ruled hits were instead ruled as errors. “I remember a couple I hit right up the middle when they said the shortstop was out of position, so they called them errors.”

- The story of the Hanshin Tigers’ Randy Bass pursuit of the single-season home run record is well-documented. Bass had 54 home runs and needed one more to tie Sadaharu Oh’s record. In the last game of the season against the Yomiuri Giants – managed by Oh – opposing pitchers walked Bass four times. Leon had a similar experience. He hit 16 home runs against the Kintetsu Buffaloes one season. One more would have broken the record, so the opponents walked him. “I even hit from the other side of the plate once, and they walked me,” he said.

- After Leron won the 1980 batting championship, the team gave him his silver bat in the clubhouse rather than making the presentation in front of fans, as they likely would have with a Japanese player.

- Despite his prodigious resume, Leron had no equipment sponsorships and had to buy his own bats. A Tokyo advertising executive told him that Japanese did not want black role models.

Further, the Japanese media and members of the baseball community in Japan didn’t want foreigners to overshadow the Japanese, so their accomplishments were taken for granted, while their struggles were intensely criticized. It sometimes seemed to the brothers and other imports as if they were starring in a vacuum; that their successes made little difference to their perception. “They make it painfully clear that you’re always a foreigner,” Leon commented. For example:

- Leron recalls that in 1980, “It made headlines one day when the Buffaloes shut us both down in one game. The next game, I had three home runs and Leon two by the fourth inning, but there was no headline about that in the next day’s papers.”

- When Leron broke the record for career hits for a player with 4,000+ at bats, the league responded by immediately creating new categories for those with 5,000+ and 6,000+ at bats.

- After winning the home run and RBI championships but barely missing out on the batting title in his brilliant first season, a team executive said the team might have taken the pennant if only Leron had won the Triple Crown.

- Leon remembers a game in which he hit two home runs and had six RBI, but his team lost 8-7. The newspaper story focused on the fact that he’d stranded two runners in his first at bat, adding that Americans were paid a lot of money and questioning his ability to win games.

- In 1985, after a season in which he had batted .303 with 31 home runs and 110 RBI in 128 games, the Whales released Leon. Why? The club said he didn’t hit when the team needed him to. When he asked for an explanation, he said that he was told, “Don’t ask for a reason. Go on with your life.” He did, playing two solid seasons with the Yakult Swallows.

Leon summed it up in a 1989 article: “Our job is to do well and let the Japanese players have the glory, and to take the blame when things go bad.”

“We didn’t complain, and we didn’t act spoiled. We looked at things as challenges.”

The ability to adapt, adjust, and accept the way things were was key to the Lees being successful import players.

The game in Japan was different than what the brothers learned growing up in California – a greater emphasis on fundamentals and “small ball” and more off-speed pitches, among other things. That was influenced in part by Japanese culture and its emphasis on the group, as opposed to the individual.

To exemplify the emphasis on the team rather than individuals, Leon mentioned an incident regarding Hiromitsu Ochiai, an infielder now in the Japanese Baseball of Fame. In one game, Lee was playing first base and Ochiai second. A ground ball was hit between the two, but closer to Ochiai. Lee let Ochiai go for it, and it went through for a hit. Ochiai then stood with his hands on his hips and glared at Lee as if the hit was Lee’s fault.

“My brother and I had actually campaigned to get [Ochiai] on the team, so we wanted him to do well. And he did end up winning the Triple Crown. But I didn’t appreciate him showing me up like that,” Lee said. “When we got back to the dugout, I told my interpreter to tell him to ‘never’ do that again. Someone should have told him that wouldn’t be tolerated, but they didn’t get on him or me about it. Everything was supposed to be about team harmony.” (Leon was unexpectedly traded to the Taiyo Whales after the 1982 season – “They said our team had too much of a foreign influence,” he said.)

A New York Times feature on the Lee brothers further explained the team dynamic: “It is not enough to hit well, the brothers say, but to hit well using the team batting stance. It is foolish to dive for a ball, because if the ball drops the player has risked and failed and is banished to the bench.” According to Leon, there would be “five or six meetings between innings each game. It was an image thing. Coaches said it had to look like they were doing their jobs. It drove us crazy.”

Like virtually all foreigners who play in Japan, the Lees were sometimes dumbfounded by the amount of practice time Japanese players endure. Leon remembers spring training beginning in the freezing cold of early February. The players would start with a three-mile walk, have breakfast, go to the ballpark for a three-hour “warmup,” eat lunch, and then start practice. “The first month was all training. The second month, we’d play 20 games in 28 days.”

“Practice meant so much there that, if we couldn’t practice because of bad weather, they’d cancel the game – even if the sun was out by game time.”

He added that “every [game] day was like a double-header. We had two batting-practice pitchers – one lefthanded and one righthanded – and we hit for 10 minutes against each. After a while, it got to be a natural part of the day, and it made me a lot better hitter.”

“We didn’t complain, and we didn’t act spoiled,” Leon said. “We went along with things because of their idea of keeping a balance, and we looked at things as challenges. If an umpire called us out on a pitch that was a foot outside, we’d tell each other that. We adjusted to the game there on every single pitch, and it made us 100-percent better.”

They became better hitters with all the reps and unique challenges and also got into optimal physical shape. Leron said, “They told us when we first got there that practice was everything and games were second. We got in such good shape that we could play all through the season and still play well. We were as strong as gladiators in August and September.”

“Our Careers Meant Something”

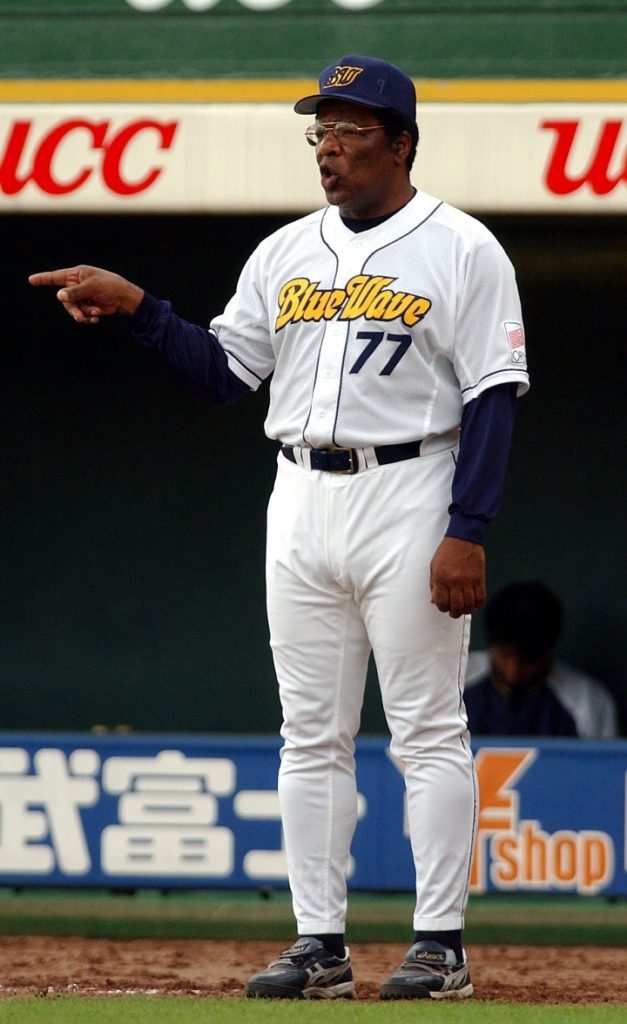

In the years since, he’s seen a lot of changes in Japan – in the level of the game, the quality of the stadiums, and in the attitude towards import players. He views the period when he played there (1978-1987) as one of transition for non-Japanese players. NPB allows more foreign players now (four, as opposed to two when he played), English is spoken more widely, and the media is much more empathetic towards foreign players. Plus, more umpires are trained in the U.S. now, so they are more neutral.

He has also observed steady on-field improvement over the years. “You see more position players coming to the U.S. and doing well. Then you see a guy like [Shohei] Ohtani, who is amazing. I’ve talked to a few guys who’ve played in Japan relatively recently, and I get the impression they realize the Japanese were better than they’d thought. A guy can’t hit .250 there anymore and be considered successful.”

In fact, Leon is more of a proponent of the Japanese game today – “They still play the ‘whole game’ there. In the U.S., there is so much focus now on things like launch angles, shifts, and other stuff. In our day, if a pitcher started pitching up in the zone, he’d be coming out. Now they teach them to do that.”

Looking back, he has an overall positive view of his time in Japan.

“One thing I learned there – which sometimes serves you well and sometimes doesn’t – is to focus on the term ‘It’s not about me.’ I realized that the more I worked for my teammates, it seemed like the better I did. It’s about finding a balance between being individualistic and playing within the team concept. I remember when [former New York Yankees standout] Roy White came over [1980-1982] to play for Yomiuri. He said that every player who signs a pro contract should play at least one year in Japan to understand the work ethic, the appreciation for the game, and the ability to be a good teammate.

“I think we kind of helped build the road for guys who came over later, like Cecil [Fielder, who starred for Hanshin in 1989]. What we did made it possible for others, so our careers meant something.”