One of the best stories in sports is the “trailblazer,” where one player becomes the first of his or her background to push historical precedent and beat the odds to become a superstar. Players like Jackie Robinson, Hank Aaron and Roberto Clemente are regularly mentioned in Major League Baseball (MLB) lore, and Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB) is no different, having players like Jimmy Bonner – the first Black ballplayer to play professional baseball – forever in their history books.

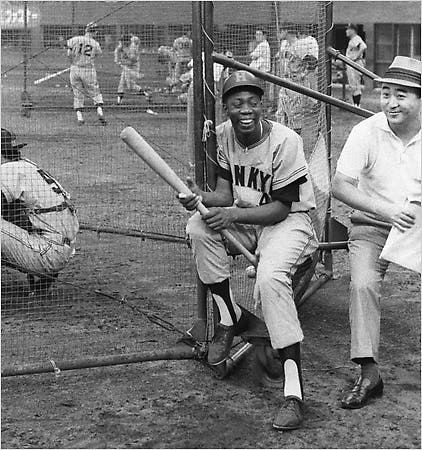

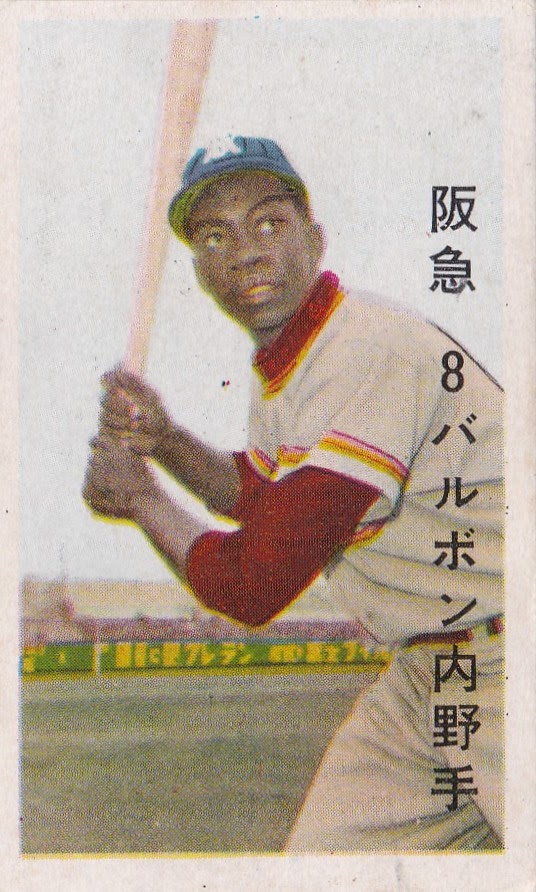

One trailblazer whose story is not told enough, however, is Roberto Barbon, a stringy infielder from Cuba who joined the Hankyu Braves in 1955 at just 21 years old. Upon his debut, Barbon became NPB’s first Latin player.

Unlike other players of the time who joined the Braves and soon returned to the MLB pipeline, Barbon did return to play in the U.S. Instead he created his own path, becoming one of the most important foreign players in Japanese baseball history.

In recognition of Hispanic Heritage Month, this is the story of Roberto Barbon – the first Latin player in Japan, the first foreigner to record 1,000 hits, the last foreigner to steal 50 bases in a season, and, perhaps most importantly, one of the best baseball ambassadors Japan has ever known.

Early Life

Barbon was born in 1933 in Matanzas, Cuba, as the youngest of 11 children. Barbon has expressed incredibly gratitude for his upbringing, explaining that he never had to suffer through the backbreaking work his father and brothers endured.

“My father cut sugar cane,” Barbon told the Kyodo News. “My brothers helped my father. I never worked in Cuba. I was lucky. During the week, I went to school. On Saturday and Sunday, I played baseball, only baseball.”

After graduating high school, Barbon crossed the channel into the States to play baseball in earnest, playing games in integrated baseball circuits in Western Canada, and playing minor league games in the Brooklyn Dodgers’ system, with the Bakersfield Indians and Hornell Dodgers. It was a difficult jump for Barbon, who dealt with segregation and other forms of racism while making his way through the leagues.

“In Cuba, there are a lot of differences (in terms of racial variety), so I didn’t care too much about it,” Barbon said. “In America it was different. California was like Cuba, but my first year I went to Georgia, Milledgeville, then on to Atlanta, then Macon. It was tough out there in the early ’50s. It was really tough.”

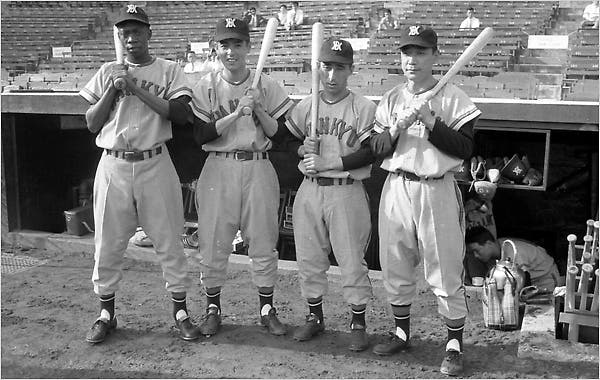

As he made his journey across the minor leagues, other players in the system were making the jump to Japan. Abe Saperstein, one of the most influential owners and promoters in sports, was in year three of his arrangement with the Hankyu Braves and their vice president, Minoru Murakami, sending minor leaguers to the team to find new success across the Pacific. This arrangement had led to the likes of Newberry, Britton, Jonas Gaines, and Larry Raines appearing for the Braves from 1952 to 1954, each posting excellent numbers and earning more hype for foreigners on the Braves. Murakami, looking for a new star to add to the rotation, asked Saperstein once again to find a player to loan.

While Barbon had performed well enough in the Dodgers’ minor league system – reaching Class “C” – there were rumors that he would be sent back down to Class D to a Tennessee team – a demotion that would sent him back into the segregated South. Knowing this and fed up with dealing with the racist surroundings, Barbon began making plans to head home to Cuba. Suddenly, an intriguing option emerged: when Saperstein approached Barbon with the offer to play for Hankyu in Japan, Barbon jumped at the opportunity, optimistic that he would find a welcoming environment in Japan.

Barbon left for Japan in February 1955, expecting temperatures akin to spring training in Cuba. Following a three-day, seven-flight journey that required several layovers, Barbon stepped off the plane expecting sunny skies and warm sun… only to be met with his first sign that Japanese baseball was a little different.

“When I got over to the ballpark, it was snowing and everyone was practicing,” he recalled. “The Japanese were practicing baseball in the snow. I thought, ‘no, it couldn’t be.’ I (had) never seen snow in my life. Man, it was cold out there. I wanted to go back to Cuba already.”

Barbon decided to stick it out for spring training, fully dedicating himself to the Japanese game by warming his hands on coals placed in the outfield and sleeping over a hot water bottle.

It would be the first of many times Barbon would adapt to the Japanese game.

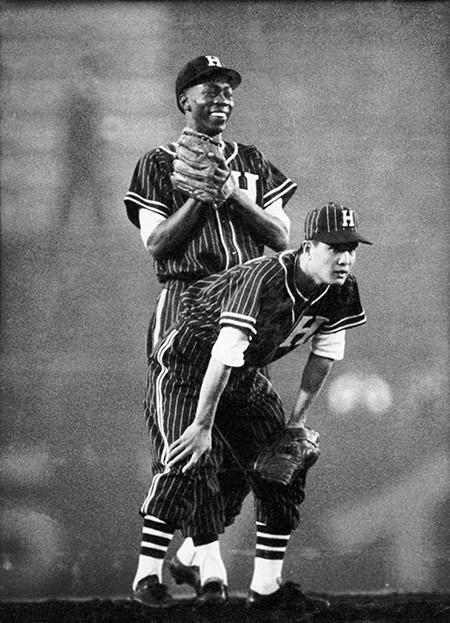

Barbon On the Basepaths

On March 26, 1955, Barbon became the first Latin player to play in NPB when he started at second base for the Hankyu Braves against the Nankai Hawks. It was an interesting experience for him, largely because he could barely understand a word anyone was saying to him.

“In the beginning, I didn’t speak the language,” Barbon said. “So I used to say everything in Spanish, they didn’t understand what I’m saying: ‘What are you talking about?’”

Fortunately, baseball is a universal language, and Barbon thrived despite the communication barrier.

Barbon dominated in his first year with the Braves, becoming the first middle infielder in NPB history to score 100 runs in a season, while also stealing 49 bases. The speedy Cuban’s work on the basepaths fit almost perfectly into the Japanese “small ball” playing style of the day – so much so that Barbon decided to extend his stay in Japan.

Barbon became one of the most well-known speedsters in the history of the game. His 308 total stolen bases are still the most all-time for a foreigner, and he led the Pacific League in stolen bases for three straight seasons, from 1958 to 1960.

While he originally only planned to stay for three seasons, finding stability in Japan became even more important to him when on January 1, 1959, the Cuban government came under the control of Fidel Castro and officially severed diplomatic ties to all “free world” countries, including the United States and Japan. Without any proper avenue to return home, Barbon found himself fully embracing his new life in Japan, marrying a Japanese woman and folding himself into the culture of the country.

Barbon Off the Diamond

One of his milestones was learning enough of the language to understand what players and umpires were saying to him. According to Barbon, one of the most prolific figures in Japanese baseball history, Katsuya Nomura, was also a notorious chatterbox, frequently getting under Barbon’s skin.

“Every time you stepped into the batter’s box, Nomura would be talk, talk, talking to you,” Barbon said. “I’d say ‘shut up man, shut your mouth’ — in Japanese.”

Beyond learning the language, Barbon was also a regular at the widely popular Japanese professional wrestling matches. After watching one match won by the famous Rikidozan – who is one of the most influential men in the history of professional wrestling – Barbon commented to a reporter that it was obvious the matches were staged. When the comments reached Rikidozan, who was also known for his connections to crime families, Barbon briefly feared for his life.

“The guy interviewed me, and we were just talking. I didn’t think it would go in the paper. If he told me, ‘I’m going to write,’ (then) I’m not going to say that,” said Barbon. “I was afraid to go to Tokyo.”

All was resolved following a written apology, and Barbon would continue to love the spectacle of Japanese combat sports… so much so that on one particular day he almost missed a game. Believing that rain in Tokyo would cancel the night’s scheduled game, Barbon headed to a sumo match and settled into his seat. It wasn’t until he heard his name being called on the loudspeaker that he knew something was wrong:

“Around 4, they announced on the loudspeaker in front of everyone: ‘Mr. Barbon, there’s a game today at Tokyo Stadium. You must go back,’” he said. “I ran outside and there was no rain. When I got to the stadium, my manager was really mad.”

No one, of course, stayed mad with Barbon for long. Affection known as “Chico-san,” by the Hankyu faithful, Barbon would end up playing eleven NPB seasons, all but one with the Hankyu Braves – the last being with the Kintetsu Buffaloes – and would become the first foreigner to notch both 1,000 hits and 1,000 games played. In fact, his 1,353 games were the most ever played by a foreigner until Tuffy Rhodes broke the record in 2007.

Even after his retirement from playing, however, Barbon still remained one of the prominent figures in the game, serving with the Braves’ front office for years as a trusted baseball mind, skilled linguist, and community ambassador.

Barbon Beyond the Game

Following his retirement, the trilingual Barbon returned to the Braves and began serving as their interpreter, helping fellow import players like Roberto Marcano become studs in their own right. Working as an interpreter, coach, and goodwill ambassador, Barbon has become a permanent face in the now-Orix Buffaloes organization, regularly engaging with fans and reporters and even coaching baseball clinics in the surrounding area.

While others may have been the first to tread international baseball waters, Barbon is perhaps the first foreigner to completely embrace the playing style of Japanese baseball. As an executive and coach, he helped new arrivals to understand and engage with the grueling practices and unique gameplay that are hallmarks of the Japanese game.

“You’ve got to get accustomed. The practice is too long, you know, but you’ve got to do it. It’s tough to get accustomed to the way the Japanese practice. You’ve got to play by their rules or hit 40 dingers. But if you get accustomed, you’ll be here a long time.”

Barbon doesn’t just represent the first Latin player in NPB, nor does he represent just the spirit of Japanese baseball; he represents the true unifying aspect of the sport. He found new passions in a different land and fully embraced the unique Japanese culture. His ongoing relationships within the baseball community in Japan further the idea that there is a role for foreigners following their time on the field; if they choose to embrace the society and customs, they just might earn a role beyond stealing bases and hitting home runs.