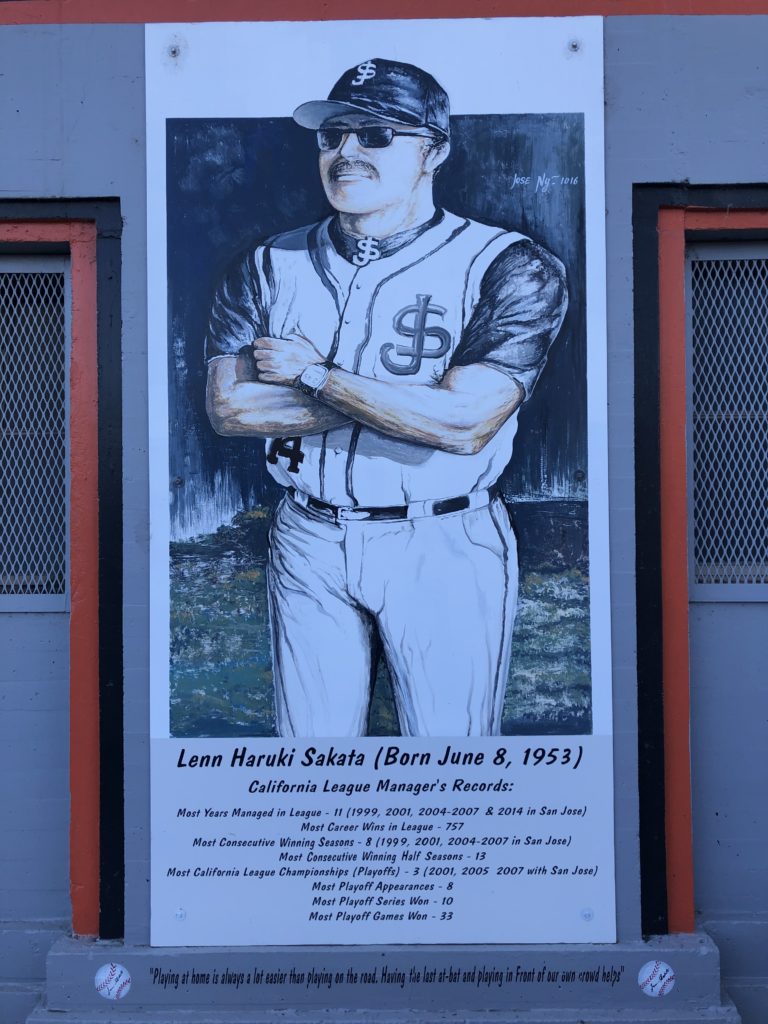

When he left professional baseball following the 2014 season, Lenn Sakata held the all-time California League record of 757 managerial wins. At 60 years old, he did not expect to add more. But just as a baseball contest does not always play out in accordance to a manager’s game plan, the same can be said of life plans.

Following a six-season hiatus, Sakata, now 67, has not only returned to the game; he once again finds himself in the Class-A California League, managing the San Jose Giants. And the wins keep piling up: as of August 15, the Giants had the league’s second-best record at 55-34.

“I wouldn’t have expected this a few years ago,” he acknowledged.

In late 2019, Sakata was enjoying retired life and playing a lot of golf in his native Hawaii. Then he heard from Kyle Haines, Director of Player Development for the San Francisco Giants.

A former position player in the Giants’ system, Haines played for Sakata at San Jose from 2005 to 2007. Following his playing career, he shifted into a minor-league managerial role and later moved to the front office. The two have had many opportunities to confer and build a strong rapport that continued even as Sakata settled into retirement.

“We’ve tended to talk a lot and about a lot of different things over the past 10 years or so,” Haines said. “There was no one particular time that we talked about him getting back into the game. It just kind of evolved over time.”

And that evolution finally materialized into something when the Giants were looking for someone to manage the Salem-Keizer Volcanoes, a Class-A club of the short-season Northwest League, for the 2020 season.

“Kyle asked me to come back, and I wanted to help him out, so I thought I’d try it,” Sakata said.

Plans changed, of course, when the Covid-19 pandemic forced the cancellation of the 2020 minor-league season and then when Salem-Keizer lost its MLB affiliation in the minor-league restructuring. The fates still willed for Sakata to return to baseball, however, and he agreed to return for a fifth stint in San Jose for the 2021 season. Sakata previously managed the club in 1991, 2001, 2004-2007, and 2014. It was in San Jose that he earned his then-record 527th California League victory on May 31, 2007.

“I like it in San Jose,” he said. “The weather is nice, the ballpark is nice, and I get to work with the younger players. That’s the part of baseball I missed the most – interacting with the younger generation.”

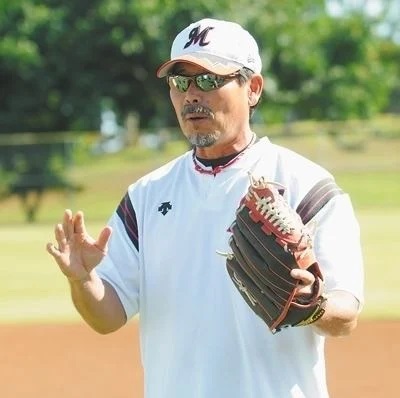

That’s something Sakata has done for a long time. This is his fourteenth year as a minor-league manager in the U.S. and his twelfth in the California League, which also includes three seasons with Modesto and one with Bakersfield.

Sakata’s success as a manager earned him Northwest League Manager of the Year honors in 1988 and, ultimately, induction into the California League Hall of Fame in 2018. He was also selected by CNN Sports Illustrated as one of the 50 greatest sports figures in Hawaii history and is a member of both the Hawaii Sports Hall of Fame and Gonzaga University’s Sports Hall of Fame.

Not only does he have the California league record for most wins as a manager, but he also holds records for number of years managed in the league (12), most league championships (3), most playoff appearances (8), and most playoff games won (33).

In the ultimate sign of respect for his tremendous impact on the hundreds of young ballplayers who have come through San Jose, the team retired his #14 in 2019 in a pregame ceremony.

Sakata’s resume also includes coaching stops with multiple minor-league clubs apart from San Jose, as well as two stints coaching and managing with the Chiba Lotte Marines organization of the NPB Pacific League.

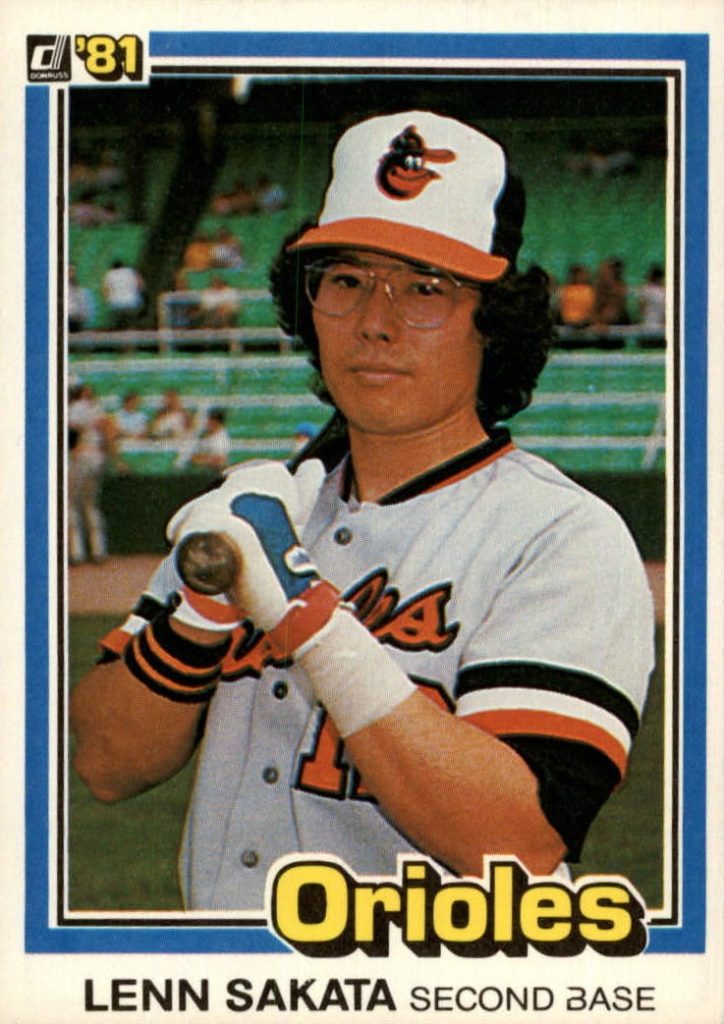

The coaching career has been the prolongation of a great ride for a young ballplayer out of Hawaii who, despite not having many expectations, became a collegiate all-American, an 11-season major-leaguer, and member of a World Series champion (the 1983 Baltimore Orioles).

From the Island to the Big Leagues

Born in Honolulu in 1954, Lenn Haruki Sakata is a third-generation Japanese-American on his father’s side. His mother was Nisei – an American-born child of Japanese immigrants – her mother having been born in Japan. His father fought in World War II as a member of the 442nd Infantry Regiment, which was comprised entirely of Japanese-Americans from Hawaii and remains the most decorated military regiment in US history. He also served with the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion that liberated the Dachau concentration camp in southern Germany.

In Hawaii, Sakata learned the game first in youth leagues, then Pony League, Babe Ruth League, American Legion, and high school. As a teenager, he competed with adults, some of them ex-professionals, in a Hawaiian Men’s League.

His father, Melvin Haruki Sakata, wanted him to play shortstop because he considered it the most athletic of the positions, but the influence of his uncle, Jack Ladra, nearly steered him toward a different position.

“My uncle was one of my major influences,” Sakata told Discover Nikkei. Uncle Jack was an outfielder in the New York Yankee organization for two seasons and one of the early Americans to play in Japan with the Toei Flyers from 1958 through 1964. “In the off-season, he would have baseball equipment around his place. I was five years old and was mesmerized by the catcher’s gear.”

Despite Sakata’s fascination with face masks and shin guards, he still ended up following his father’s guidance and began his baseball journey on the infield. Following graduation from Kalani High School in 1971, he was invited to play as a non-scholarship player at Treasure Valley Community College in Oregon after a coach noticed him in an American Legion regional tournament.

“That changed my life,” Sakata acknowledged in an MLB.com interview. “Getting off the island was huge. If I’d stayed there, I probably would not have played college baseball.” Further, Treasure Valley facilitated a position change that made him more attractive to scouts. Sakata explained that he “played second base there because the team already had a shortstop, and that was the best thing to happen because second base was a good fit for me.”

After one season at Treasure Valley, he was drafted in the 14th round of the 1972 MLB draft by the San Francisco Giants; he instead chose to attend Gonzaga University in Spokane, WA.

“My plan at that time was not big league baseball because there were so few players from Hawaii,” he said. “It didn’t seem a career option, so I was taking business classes and had the goal of becoming a high school coach.”

Only three players from Hawaii had made it to MLB by 1966. The most recent had been Hank “Prince” Oana, who played briefly for the Detroit Tigers in 1943 and 1945. But Mike Lum joined the Atlanta Braves in 1967, and John Matias made it to the big leagues with the Chicago White Sox in 1970; that same year, Kalani won the state championship with Sakata and pitcher Ryan Kurosaki, who reached the Major Leagues in 1975 with the St. Louis Cardinals.

Sakata would be next. Eventually.

Following a stellar 1974 season at Gonzaga in which Sakata led the team to a conference championship and was a second-team All-American, the San Diego Padres selected him in the fifth round of the June 1974 draft. He again did not sign.

“I turned it down because it was an insult,” he said. “Here I was, an All-American player, and they were trying to get me for cheap. I was going to turn down a scholarship for $5,000?”

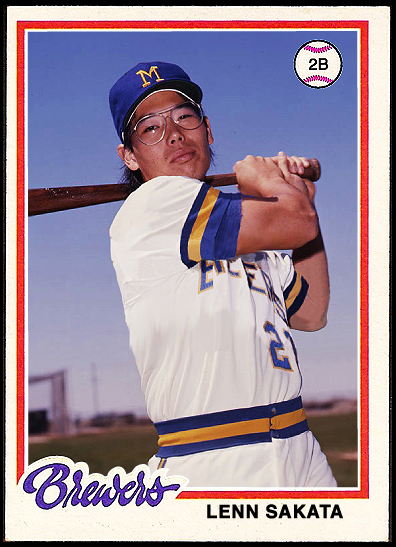

Finally, in January of 1975, the Milwaukee Brewers made Sakata their No. 1 pick in the secondary phase of the draft. Finally recognized for his true abilities, he signed with the team and reported to Thetford Mines, Quebec, of the Class AA Eastern League, making an immediate impression while earning a spot on the league’s all-star roster.

Sakata’s performance earned him a promotion to AAA Spokane in 1976, where he batted .280 with a .723 OPS. Tommie Reynolds, player/coach for Spokane that year, told the Sporting News, “He’s made some unbelievable plays… Lenny’s made a difference.” Manager Frank Howard, the 6’7”, 260-pound former slugger, once dubbed the 5’9”, 160-pound Sakata “the strongest player in our system.”

He continued to outperform through the start of the following season at Spokane. Sakata was averaging .304 with a .790 OPS over 94 games before getting promoted to the big leagues and batting .162 the rest of the 1977 campaign.

The next season, Sakata earned a big league job in spring training but soon found himself back in Spokane after 22-year-old rising star shortstop Robin Yount chose the Brewers over a golf career. Another shortstop, Paul Molitor, was drafted by the Brewers that year and was expected to progress quickly through the minor leagues; to clear his path to Milwaukee, he was moved to second base. The two young future Hall of Famers left Sakata as the odd man out.

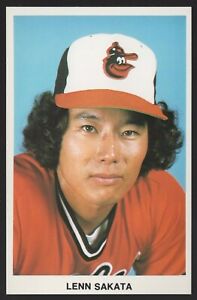

Sakata played in just 30 big-league games in 1978 and a mere four in 1979 before being traded to the Baltimore Orioles for pitcher John Flinn. He began the 1980 season at AAA Rochester but was called up to the Orioles in May. He would bat .193 across 90 plate appearances while committing only two errors in 200+ innings on the infield.

“Earl Weaver made me a major-league player,” Sakata told the Baltimore Sun of the former Orioles manager. “He saved my career. In Milwaukee, all they did was tell me how crappy I was. I once went six weeks there without stepping on the field. But Earl used everyone to win the game. Just wearing the Oriole uniform made me feel like I was worth something.”

Sakata played six seasons in Baltimore and has the distinction of being the transitional figure between two great Oriole shortstops – taking over for defensive stalwart Mark Belanger in late 1981 before relinquishing the spot to Cal Ripken, Jr. the following year.

Ripken had been expected to be the everyday shortstop when he came up in August 1981 but he batted just .128, and Sakata replaced him. The next season, on May 30, 1982, Ripken began his record-breaking consecutive-game streak, starting at third base. Ripken would eventually make the permanent transition to shortstop, starting every game at the position until 1996.

“When I walked into the clubhouse, the lineup was always by the doorway,” Sakata recalled. “I looked, and my name wasn’t in it. I looked at who was playing short. It was (Cal), and it hit me like a hammer over the head: I’m done. I’m not playing anymore.”

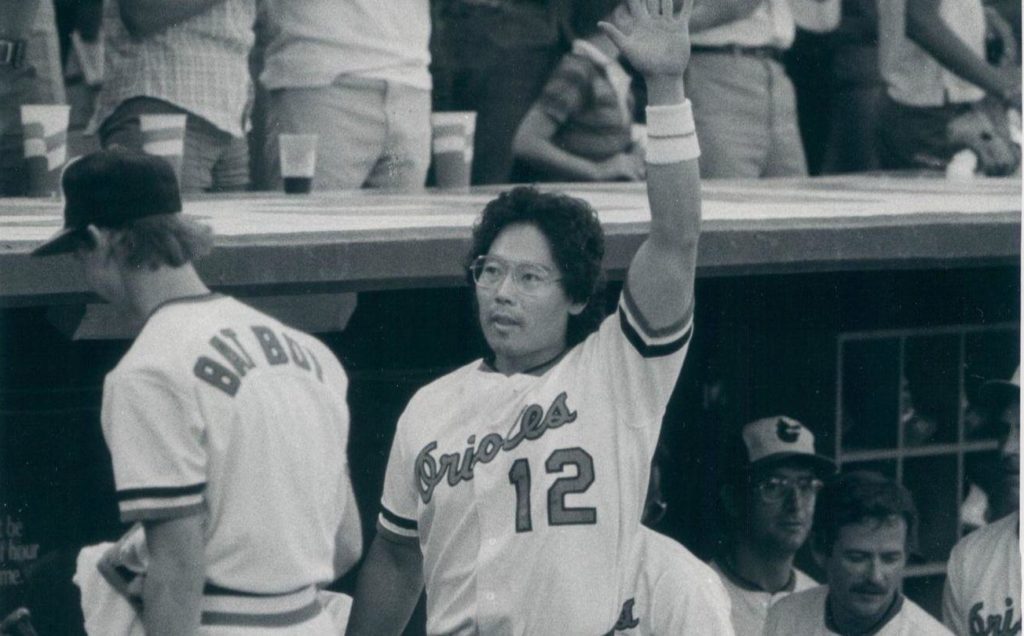

But he wasn’t done. He switched to second base and had his best season statistically in 1983, batting .259 with six home runs, 31 RBI, and a .693 OPS. He then helped the Orioles win it all, serving as a utility player and becoming the first Japanese American to appear in a World Series game.

A particular highlight of that 1983 season came in late August, in a home game against the Toronto Blue Jays. The Orioles had replaced their starting and backup catchers in a ninth-inning rally that tied the game. Sakata was inserted in the 10th inning behind the plate, a position he hadn’t played since Little League. Three Blue Jay hitters reached base and took egregious leads, assuming it would be easy to steal off the inexperienced catcher. However, Baltimore pitcher Tippy Martinez picked all three runners off first base to end the threat. Sakata would then hit a walk-off home run in the bottom of the 10th, which was perhaps the offensive highlight of his career.

“My legs felt so heavy, I didn’t know if I could catch another inning,” he said. “All I wanted was to get a hit, but the pitcher hung one, and I put it over the fence.”

A Natural in the Dugout

He stayed with the Orioles through the 1984 season, split 1985 between the big club and AAA, and then signed with the Oakland A’s for 1986, batting .353 across 17 late-season games. The following year, he played in 19 games for the New York Yankees before tearing ankle ligaments while sliding back into second on a pickoff attempt. The Yankees released him after that season, effectively ending his playing career.

Befitting the stereotype of a “grinder” on the field who thrives in the dugout, Sakata quickly transitioned into coaching, where in addition to compiling the wins, he’s demonstrated a penchant for mentoring and guidance, apparent in the words of those he has influenced.

“He has so much experience,” Haines proclaimed, “and he’s really in-depth. He doesn’t miss any details. He’s not a man of many words, but everything is well thought-out. He sets a high bar, but once you realize how much your career means to him, you see that he has your best interests at heart. He knows what’s necessary to push you forward.”

“Lenn has been able to adjust his style to those of others and make things work,” Haines continued. “He’s accepted the challenge of working with people from different generations and found ways to communicate with them all.”

Author and filmmaker Kerry Yo Nakagawa – director of the non-profit Nisei Baseball Research Project – has known Sakata since the late 1990s, when he was researching his book, Through a Diamond: 100 Years of Japanese-American Baseball. A resident of Fresno, CA, Nakagawa recalls when Sakata was manager of the Fresno Grizzlies in 2001.

“John Carbray, the owner, was able to get Lenny to manage that season,” Nakagawa beamed. “We have a great photo of me, Lenny, John, and Pat Morita [of “The Karate Kid” movies] breaking open a sake barrel, which is a traditional good-luck ceremony when you start a new business or have a special event.”

“That year, Lenn really helped my son, who was a catcher on travel teams,” Nakagawa went on. “He immediately saw a flaw in his throwing motion and also helped him as a hitter. My son learned more from him in a half-hour than from his high school program and those elite teams he was on.”

A Japanese Baseball Adventure

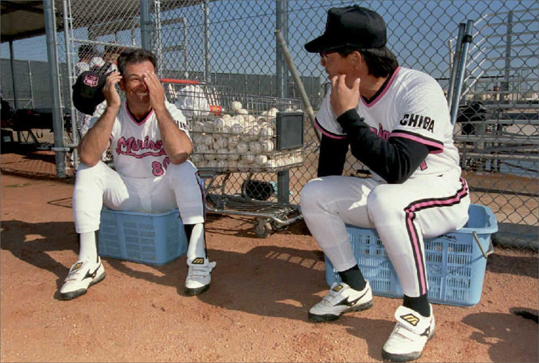

Sakata coached in the Oakland system from 1988 to 1990 and in the California Angels’ chain from 1991 through 1994. He then joined Nippon Professional Baseball’s Chiba Lotte Marines in 1995, Bobby Valentine’s first year as manager, and stayed through 1998, serving two seasons as the club’s minor-league manager and then two as a coach with the big-league team.

Though the team had managed a surprising second-place finish in the Pacific League in 1995 – his first season – Valentine was fired after a personal conflict with the general manager.

Sakata felt uncomfortable when he assumed the role. “I couldn’t speak Japanese very well,” he admitted, adding that it “felt like I was really a foreign element, and it did bother me. Even though they treated me nicely, I’m pretty sure they didn’t like me. This was going into even my own coaching staff.”

Regardless of the dissonance he felt, Sakata still views the overall experience as a positive one.

“Watching how they played made me think differently about the game,” he said. “I didn’t understand a lot at first, but then I started picking up on things like they rarely call balks, which makes it harder to steal. Hitters there didn’t get as many fastballs, and Japanese pitchers threw five pitches, so it was harder to predict which pitches are coming.

“Besides that, I learned more about dealing with different types of people. That’s served me well because there are always going to be different people and different situations to deal with. I would have stayed in Japan longer if I’d had the chance.”

He got that chance nine years later, spending 2008 and 2009 again working with Valentine and the Marines, and he had a somewhat different experience.

“[The Japanese teams] have more ability to interact with MLB now, so it’s changed some of what they do over there,” Sakata said. “It’s still the Japanese game, but the generations coming into baseball now have become more westernized, if you will. It seems that Japanese players are more worldly now . . . They want to see what’s out there.”

A California League Fixture

Valentine was fired again after the 2009 season – club officials reasoned that they couldn’t afford his salary and remained firm in the face of tremendous fan support for Valentine – and Sakata came home as well. He was hitting coach for Asheville in 2011, Modesto manager in 2012 and 2013, San Jose manager in 2014, and then went home to Hawaii.

“I’m not sure I totally fit in with the [Giants] organization back then,” he said, “but the organization and how it’s run is totally different now.”

While Sakata acknowledges it would be nice to be asked to interview for a major-league job, he seems content with his position.

“At my age, I don’t have aspirations of moving up the ladder,” he said. “I’m here to make sure that things are organized and to help young players develop a foundation that will get them to the big leagues eventually. It’s always been a joy for me to see some of the kids I’ve managed reach the highest levels of the game.”

And he has several this season that could eventually accomplish that, though Sakata speaks cautiously. His team this year has had eight players ranked among San Francisco’s top 30 prospects, including shortstop Marco Luciano, outfielders Luis Matos and Alexander Canario, and pitcher Kyle Harrison.

“They have a chance to be the types of players everyone expects,” he said. “It depends on how hard they work and how well they discipline themselves to do all that is necessary.

“This is a situation where I can have the best impact. The players are eager and more impressionable. I feel fulfilled at this level.”