Quick: name the greatest baserunner in baseball history.

Chances are, you said Rickey Henderson, and there’s not much surprise in doing so. Henderson is the world leader in stolen bases with 1,406; that’s nearly 500 more than Lou Brock, Major League Baseball’s second-best baserunner, who originally held the record with 939. When Henderson broke Brock’s all-time stolen base record in 1991, he was famously quoted as saying “I’m the greatest of all time,” a statement that would go on to follow him for the rest of his career.

Here’s the thing: he still had one more record to break. A Japanese ballplayer had broken Brock’s record nearly eight years earlier – a speedster who, like Henderson, was a fantastic leadoff man and one of the best players in the world. Unlike Henderson, however, he was a bit more on the quiet side, more reserved and humble with his accomplishments.

His name is Yutaka Fukumoto, and this is the story of how he became one of the greatest of all time.

Humble Beginnings in Osaka

Fukumoto was born on November 7, 1947 in Ikuno-ku, Osaka, to two loving parents, a father who owned a ramen shop and a mother who operated a futon-tailoring business. He played scrimmage-style baseball games all through elementary school, but was known more for his antics off the field than on it. He was a regular around town, delivering packages for his mother after school, and once, when chasing a ball into a nearby river, he was distracted by the fish and focused on chasing them instead.

Fukumoto continued to play sandlot-style baseball and got his first true yakyu experience at Daitetsu High School. While most of the first-year players left the team due to the intense rituals initiated by the upperclassmen, Fukumoto stayed and played as a right fielder, earning him valuable first-team reps. By his sophomore year, he had emerged as the team’s star center fielder and leadoff hitter – two positions that would define his career.

He helped Daitetsu reach the Koshien Summer Championship tournament in his junior year but lost in the opening round due to a pivotal defensive lapse: Fukumoto and the second baseman both went after a bloop hit to centerfield and a miscommunication caused the ball to drop. Fukumoto made a private note that if he had been a better teammate and communicated more effectively, they would have likely won the game. Following the loss, cooperation became a critical focus of Fukumoto’s career, and he became the ultimate team player.

After graduating, Fukumoto briefly played in the industrial league (a semi-pro league of corporate-sponsored teams) for Matsushita (now Panasonic), where he was named to the “Best Nine” for amateurs. He was still not satisfied, however, saying, “I’m not a notable player as an amateur.”

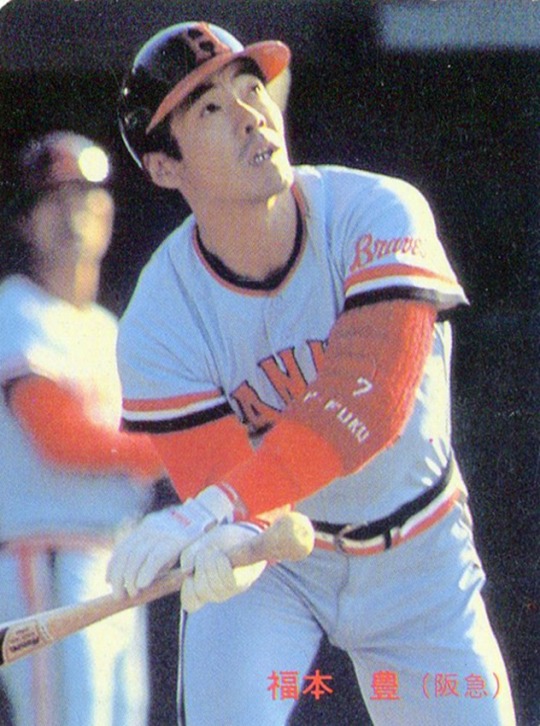

While he found nothing interesting about his amateur career, other scouts certainly did, as the speedy outfielder was taken seventh overall by the Hankyu Braves – now the Orix Buffaloes – in the 1968 Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB) draft. Fukumoto didn’t even realize he was eligible and only heard the following day when his colleague mentioned reading about him in the sports pages.

The surprised Fukumoto wouldn’t sign a contract until he had a proper conversation with the scouts that took him. Upon meeting the team for the first time, the center fielder was treated to a meal and immediately realized, “If I become a professional, I can eat such delicious meat!” Fukumoto reportedly did not sign a contract until the fourth meeting, being taken to dinner each time before finally signing. After a journey that seemed straight out of a sitcom, Fukumoto had gone from a kid chasing fish in the river to catching a major contract.

Innovative Strategies to Become an Offensive Threat

Fukumoto played with the Braves right away in 1969, often appearing as a pinch runner. After a few appearances, however, the 21-year-old was sent down to the minors, with kantoku (manager) Yukio Nishimoto telling him to work on stealing bases so that he could be more of a threat off the bench.

However, Fukumoto wanted more than just to be a threat on the base paths. He had noticed the high level of batting ability from his major league teammates and thought to himself that as the seventh overall pick in the draft, he had the expectation to perform at the plate, not just on the basepaths. He made a silent commitment to himself: if he did not do well after three years of playing, he’d retire from the team.

Fukumoto committed himself to the batting cage, trying to develop more power and skill with the bat. He was even seen practicing after hours in the dorms, judiciously smacking at the tip of a leaf of a house plant with his bat. He worked long hours trying to become the best player he could possibly be. The coaches at Hankyu noticed his effort and decided to assign him a personal coach that would become a godsend: Kiyoshi Asai.

The noticeably odd thing about assigning Asai to work with Fukumoto? Asai was not a ballplayer but rather a track star, having posted a stellar 100-meter time of 10.5 seconds and racing for Japan in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. Impressed with Fukomoto’s raw speed, Asai gave the young athlete several sprinting tips that helped turn the prospect into a star, including “how to run without shaking my elbows” and how to efficiently reach top speed when stealing a base.

The training worked: Fukumoto returned to the Braves in 1970 and won his first stolen base crown, notching 76 steals on the year. His hitting received less attention, but Fukuomoto was proud of his 116 hits and eight home runs – he had successfully proven his ability to handle the bat at the big-league level.

Fukumoto, however, was still worried that he would not last as a professional and had a friend from high school regularly tape his games as proof that he was once in the major leagues. Meticulously rewatching the tapes in the offseason, he noticed something peculiar about the pitchers when a runner was on base: most had a rhythm that included a telltale sign if they were going to focus on the batter or pay sufficient attention to the baserunner, perhaps throwing a pick-off attempt to keep him close. For some pitchers, it might be a foot raising just before the delivery; for others, a grimace as they geared up to throw a pitch.

Fukumoto applied his learnings the following season, and the strategy worked to perfection: in 1972, he notched the current league record for stolen bases in a season with 106.

Throughout Fukumoto’s career, he followed what he called the “three S’s:” start, which was brought on through careful study of opposing pitchers; speed, which he learned from Asai; and sliding. While other talented base stealers would often slide head-first into the bag (Henderson’s slides were things of legend), Fukumoto preferred to glide in feet-first, always leading with the left leg and turning his back to protect against errant throws, and would spring up to standing upon impact with the bag. He did so because it put him in a position to advance further if the throw got away, and he was wary of the potential injuries that head-first sliding presented (he often preached to teammates and others about the dangers of the practice).

Fukumoto had put the work in and was now ready for a storied major league career, perhaps one of the best NPB has ever seen.

Green Light to Steal: An Overview of Fukumoto’s NPB Career

After winning his first stolen base crown in 1970, Fukumoto earned a rare freedom in Japanese baseball: he had a “green light” to attempt a stolen base whenever he wanted to. Fukumoto, with his exemplary skill, had escaped the need to be micromanaged in a notoriously top-down profession and had free will over the basepaths.

He took this to heart and began to impose his will on the bases. After notching 67 stolen bases and 118 hits in 1971 – earning a Pacific League pennant with the Braves in the process – Fukumoto had his breakout season in 1972, stealing the aforementioned 106 bases – a new Japanese record – and tallying 142 hits, scoring 99 runs in the process. The 106 total was a new world record for stolen bases in a season, surpassing Maury Will’s MLB record of 104 set in 1962, and was the first-ever triple-digit stolen base total by a Japanese player. He was also the first stolen base king in NPB history to be named Pacific League MVP and led his team back to the Japan Series, losing for the second straight year to the mighty Yomiuri Giants.

Fukumoto never wavered, staying with the team that drafted him and becoming their star player. As his star continued to shine – notching 100 runs and 95 stolen bases in 1973 and 84 runs and 94 stolen bases in 1974 – the Braves kept building a strong team around him, setting up a dynasty in the making. The team finally broke through in 1975, when they won the Pacific League pennant and beat the Hiroshima Carp for their first Japan Series championship. The team went on to win three straight titles, becoming the first sustained success story in NPB after the mighty Giants. Fukumoto’s best Japan Series performance came in 1976, when he was named series MVP with an all-around stellar performance: 11 hits, a .407 batting average, and two home runs in a demon-exorcizing victory over the Giants.

In addition to his fantastic offensive output, Fukuomoto was one of the best center fielders ever to play Japanese baseball, winning 12 “Diamond Gloves” (then the equivalent of Gold Gloves), an NPB record. Fukumoto was the master of putouts on fly balls, holding the unofficial record for putouts with 5,102 out of a record 5,272 defensive opportunities. One notable example occurred in the 1972 All-Star Game, when he ran to the outfield fence, climbed up “like a monkey,” as the legendary slugger Shigeo Nagashima described, and caught the ball. Of course, the ever-humble Fukumoto didn’t see himself as anything exemplary: “Any outfielder can do it as long as he runs in a straight line to the ball’s landing point,” he later wrote.

Fukumoto continued to have a standout career even beyond his prime years in the 70s. After setting a new Japanese record for career stolen bases with 596 – doing so in 1977, as the former record-holder, Yoshinori Hirose, looked on from center field – he set a new Pacific League record for runs in 1980 when he scored a whopping 112, and helped the Braves win two more pennants in 1978 and 1984; all the while, he was the Pacific League’s stolen base leader for 13 consecutive seasons, leading the pack from 1970 to 1982.

Needless to say, other teams took notice of the star player and often tried to slow him down. Both the Seibu Lions and the Lotte Orions (now Chiba Lotte Marines) admitted to attempting to hamper his steps by spraying the first-base path down with water before games against Fukuomoto’s teams. The Nankai Hawks, managed by the legendary Katsuya Nomura, would frequently walk the ninth batter with two outs so they would not face Fukumoto as a leadoff batter the next inning. Nomura also taught his pitchers a “quick pitch” when Fukumoto was on base so that he would not be able to detect their lead legs raising as easily to get a good jump. Upon Nomura’s death in 2020, Fukumoto said that these countermeasures were effective in lowering his stolen base count and made him raise his game even more.

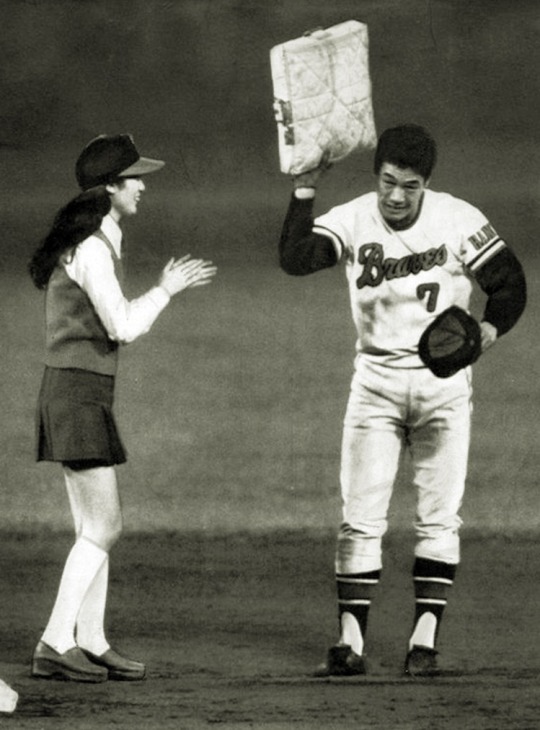

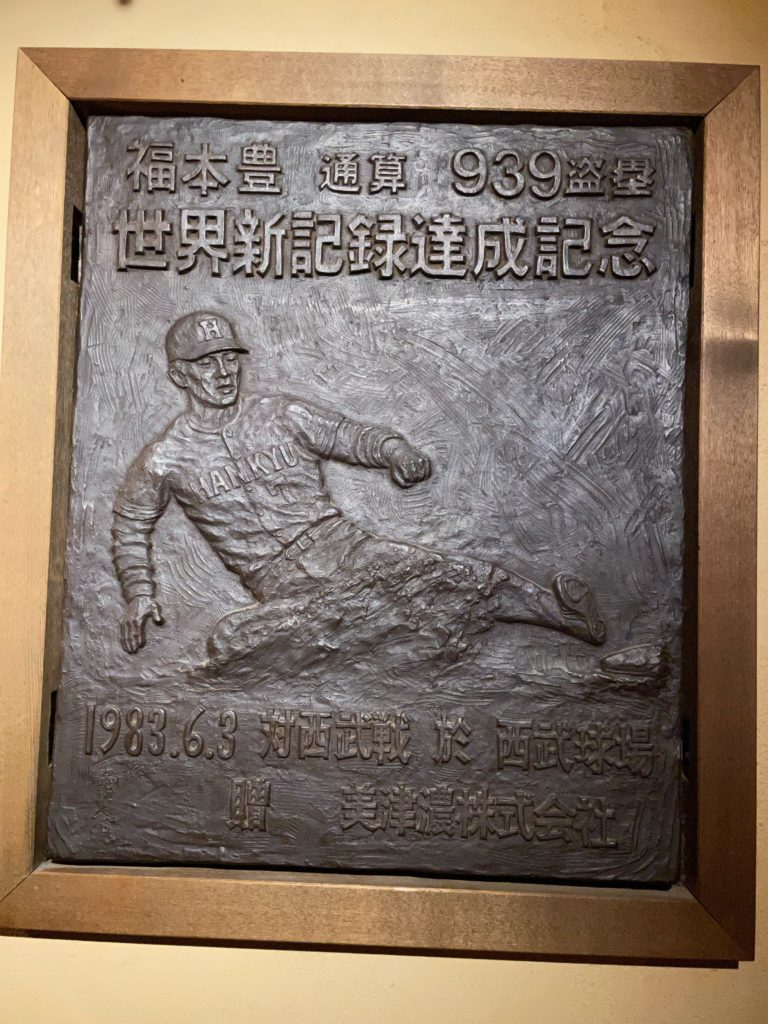

On June 3, 1983, during an away game against the Lions, Fukumoto stole third in the ninth inning and became the all-time world record holder for stolen bases, passing Lou Brock. Fukumoto was a bit sour that he set the record on that particular day, for he – along with the rest of the Hankyu team – was hoping that he could set it in a home game at Nishinomiya Stadium. He even called it “a very depressing world record.” The achievement was still celebrated, however, as Seibu set off fireworks for Fukumoto; it was the first time they had done so for an opposing player.

How Fukumoto Stacks Up

Fukumoto retired with several NPB records, some of which he still holds today: triples (115), leadoff home runs (43), total career stolen bases (1,065), stolen bases in a season (106), and times caught stealing (299).

Despite this, Fukumoto often refused to acknowledge himself as a star player. He frequently shrugged off his achievements, saying things like “anyone could do it with enough training.” He did not consider himself a star of the Braves team but rather just another player – albeit an important one – in the system. When he broke the NPB stolen base record in 1983, he famously refused to accept the National Honor Award from the Japanese prime minister, believing himself not to be a “role model,” since he “smoked and played mahjong.” Even years later, he is proud of his refusal of the award.

The humble Fukumoto was a kind man who worked tirelessly in the community. The Braves required their first-year players to visit local retirement homes and engage with the residents; unbeknownst to most, Fukumoto continued this practice all 23 years he served with the team. He also visited hospitals for the physically handicapped and taught them to play baseball, later becoming the honorary chairman of the Japan Baseball Federation for the Physically Disabled.

Perhaps the most noteworthy example of his character came at the very end of his career in 1988, when the Braves finished their final season before becoming the Orix BlueWave. As skipper Toshiharu Ueda addressed the loving crowd in a farewell address, he misspoke and told the crowd that Fukumoto was leaving the team with another retiring teammate rather than joining the BlueWave. Fukumoto was surprised, believing he had at least one more year in the tank, but when pressed by reporters, he met the question with his usual attitude: a shrug and saying, “Ueda said so, so I’m retiring.”

Afterward, he worked as a coach and commentator but kept to himself for the most part. He was more frequently seen fishing than he was in a major league ballpark, though he still put on his Hankyu threads for celebratory occasions.

Fukumoto vs. the World

With his resume full of awards, records, and championships, it’s clear that Fukumoto compares well to his major league counterpart, Rickey Henderson; while Henderson was the “Greatest of All-Time,” Fukumoto still remains the Japanese stolen base king and second on the world leaderboard.

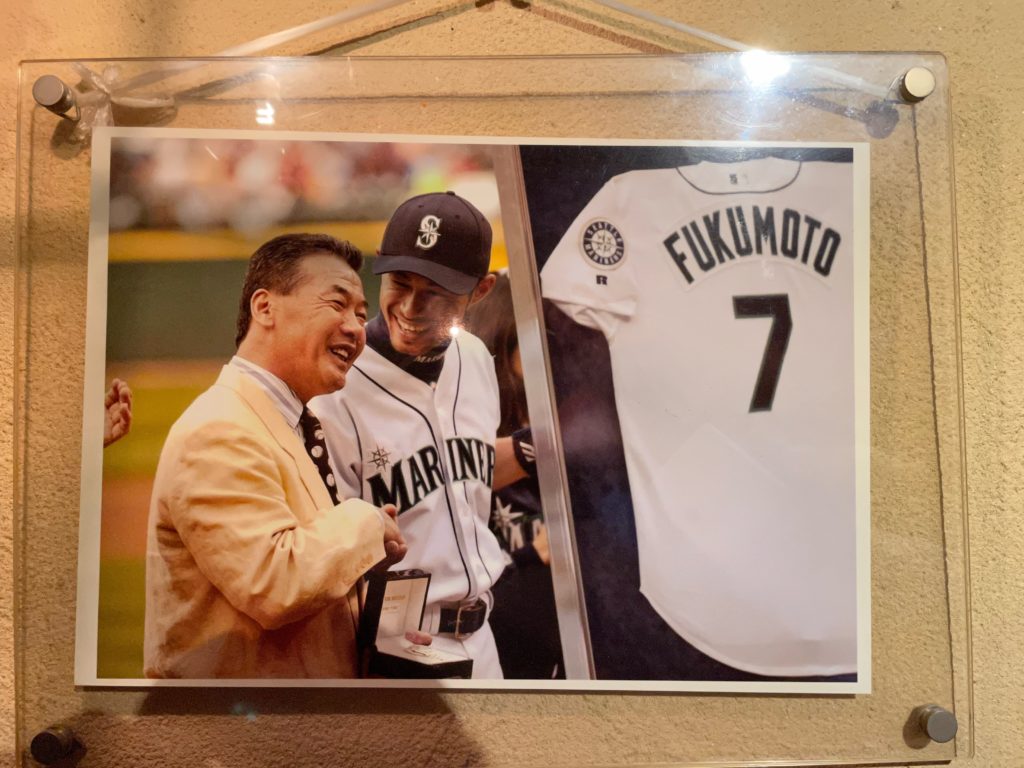

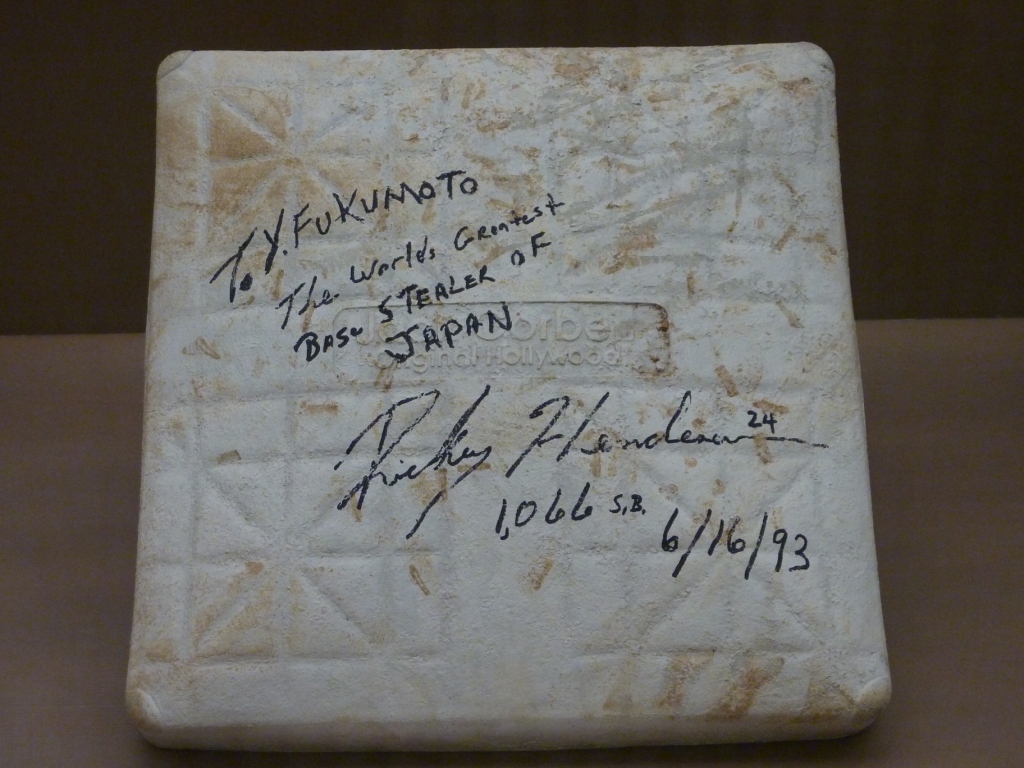

The two, however, do share an even more direct connection. In the first inning of a game against the Chicago White Sox on June 16, 1993, in Oakland, Rickey Henderson took off for second and slid in safely with his trademark head-first slide; in doing so, he surpassed Fukumoto and became the world record holder for stolen bases. Henderson promptly picked up the bag and sent the souvenir into the Oakland dugout.

Can you guess where the bag is now? It isn’t in Cooperstown, nor in Henderson’s personal collection…it’s in the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame in Tokyo, courtesy of Fukumoto, who was given the base with an inscription scrawled in sharpie from Henderson:

“To Y. Fukumoto, the world’s greatest base stealer of Japan.”

Fukumoto traveled to Oakland to watch Rickey pass his record. The two legendary base robbers met before and after the game to celebrate each other’s achievements. It was a global baseball connection surpassed perhaps by only the first meeting between the two home-run kings: Sadaharu Oh and Hank Aaron. Fukumoto and Henderson exchanged gifts for the occasion: for Fukumoto, the base; for Henderson, a pair of golden cleats. Henderson, the owner of one of the biggest egos in MLB history, treated the humble star with respect.

The two “world’s greatest” at their craft demonstrated a genuine connection despite their cultural and language differences. Two stars from opposite sides of the Pacific, united by their mastery of baseball theft.