Though Alex Ramirez and Randy Bass were elected to the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame on the same day and had similar careers in many ways, their paths to Japanese baseball immortality were certainly not the same. One had pretty much a direct shot, while the other took the long way.

Both went to Japan’s Nippon Professional Baseball after playing approximately 130 games over parts of several major-league seasons. In Japan, both hit for average and power, made all-star teams, won numerous awards, and helped lead their teams to championships. They were fan favorites, despite being gaijin, or outsiders.

And when their inductions were announced on January 13, they became the first non-Japanese-born members of the Hall of Fame since Wally Yonamine in 1994 and doubled the overall count (joining Yonamine and the Russian-born pitcher Victor Starffin, elected in 1960). The two sluggers, who will be forever linked as members of the Hall’s 2023 class, are the only inductees who played in the major leagues before coming to Japan. They will be formally enshrined later this year along with composer Yuji Koseki, who wrote the Hanshin Tigers’ iconic official team song, “Rokko Oroshi.”

But while it was less than a ten-year wait for Ramirez, who is a Japanese media darling, it took 35 years for the more-maligned Bass to earn enshrinement.

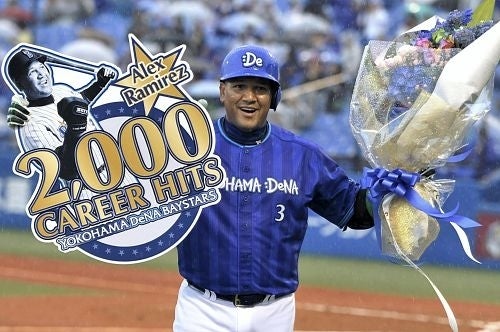

Ramirez, from Caracas, Venezuela, played 13 seasons in NPB, with his final game coming in 2013. He twice won the Most Valuable Player Award, was a key factor for both the Yakult Swallows and Yomiuri Giants when they won Japan Series titles and became the first foreign player to surpass the 2,000-hit mark. He led the league in batting average once, was an eight-time all-star, and was named “Best Nine” (the best player at each position, as voted on by a panel of writers) four times. For his career, he hit .301 with an .858 OPS and 380 home runs. His power remained consistent throughout his NPB career, as he averaged 29 home runs per season (the equivalent of 35 home runs per 162 games).

After retiring as a player in 2013 at 38 years old, he then managed the Yokohama DeNA Baystars from 2016-2020, guiding them in 2016 to their first playoff appearance in 18 years and taking them to the 2017 Japan Series, where they fell to the Fukuoka SoftBank Hawks.

“Rami-chan,” as he was affectionately referred to by his adoring fans, had what one writer referred to as an “effervescent personality” and had home-run “performances” that sometimes included the team mascot. Fans loved him and he found a welcoming home in Japan. He even managed to become a Japanese citizen – a notoriously difficult process for a foreigner.

Ramirez was named on 290 ballots by the Player Selection Committee and received 81.7% of the vote to surpass the minimum 75% required for induction. However, Bass, despite five-plus record-setting seasons, was not elected in his 15 years on the ballot in the Players Division and fell four votes short in the 2022 Experts Division voting. He finally got over the threshold this year with 78.6% of the vote.

Why? Jim Allen, a long-time Japanese baseball journalist, believes the difference is “attributable not just to the length and quality of their careers but also to the horrid selection process that was used until the last decade or so, and the amount of controversy that stuck to the two.” Or lack thereof: though both were very popular with the fans, there was little to no controversy surrounding Ramirez while Bass’s career ended in an unfortunate situation that was blown far out of proportion by the media.

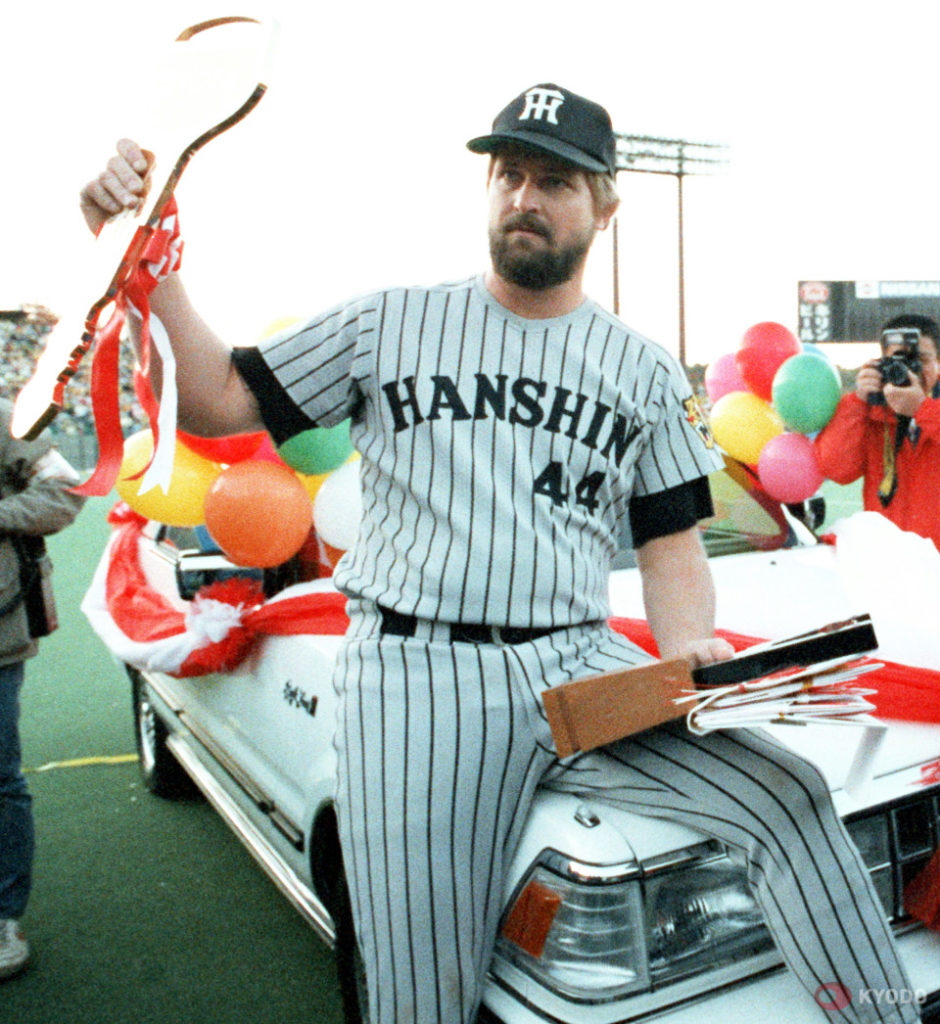

Bass’s predicament came early in the 1988 season when Bass took a leave of absence from the Hanshin Tigers and returned to the United States to be with his son, who had been diagnosed with brain cancer. He was absolutely vilified by the media for not putting the team above all else, and the club tried to release him, saying that he had not been given permission to leave. However, Bass produced a tape recording of a call proving that he had indeed received permission. Though the 34-year-old Bass was still hitting well, he did not return to the Tigers or play elsewhere again in professional baseball (he did, however, stay busy in retirement, returning to his native Oklahoma to serve as a State Senator from 2005 to 2019).

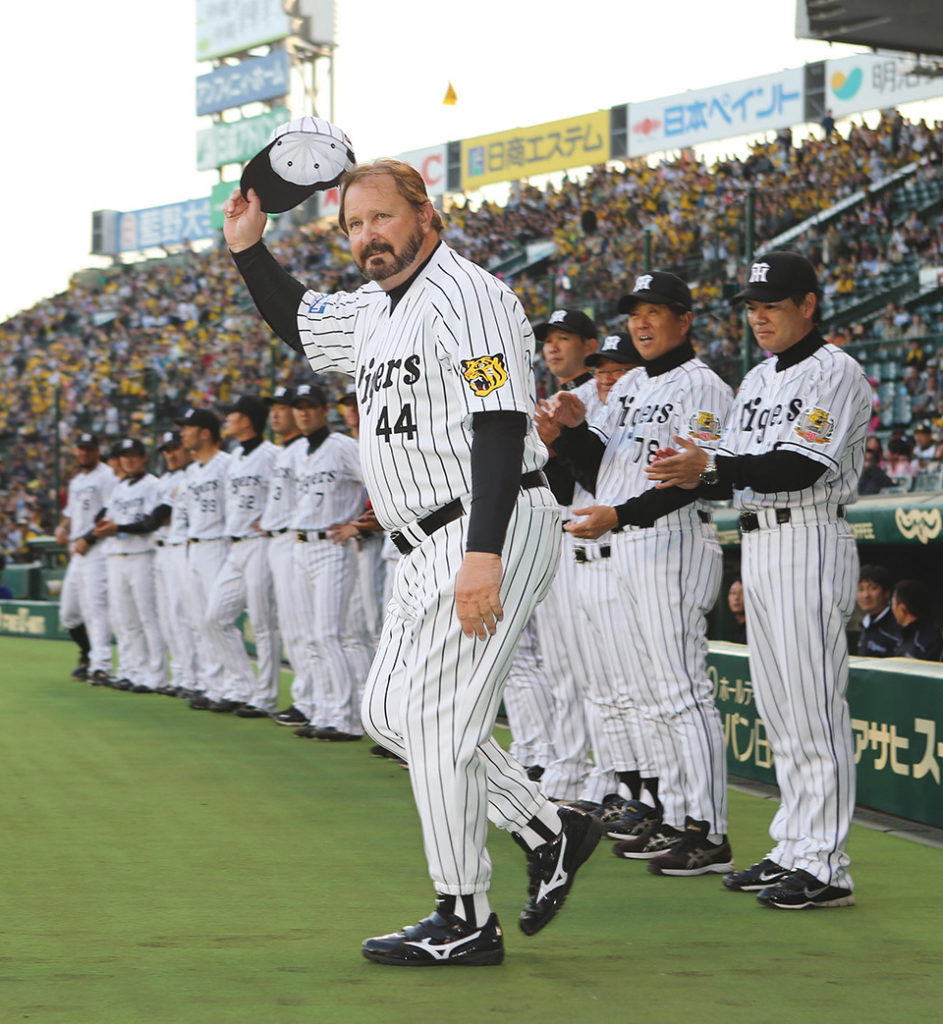

One has to wonder if the controversy, combined with his status as a foreign-born player, biased some Hall of Fame voters against him, delaying his well-deserved election. The snub certainly could not have been related to his performance. Up to then, Bass had been transcendent, averaging .337 with a 1.078 OPS and an average of 40 homers per year in his five full seasons with the Tigers. His .389 batting average in 1986 is the highest in Japanese pro baseball history, and his career mark is second only to Ichiro Suzuki (.353) among players with 2,000 or more at-bats in NPB. He twice won the Central League triple crown and was MVP of the 1985 Japan Series when Hanshin won its only title.

In 1985, he had 54 home runs going into the last two games of the season – one short of the then-record held by Sadaharu Oh. The games were against the Yomiuri Giants, managed by Oh. In the last game, Giants pitchers walked him in four of his five at-bats, robbing him of a shot at the record.

And Bass certainly had been a fan favorite. Today, he is often invited to Japan to play in old-timers games, and writer/historian Robert Whiting, an author of multiple books on Japanese baseball, once said Bass could win a fan vote for the most popular foreign player to ever play in NPB.

Like all foreign players, both Bass and Ramirez had to work hard to adjust to the Japanese culture and a different approach to the game, and they accomplished that to a greater degree than most.

Bass specifically thanked his first manager, Motoo Ando, and batting coach Teruo Namiki. “Ando-san was the first manager I had who really stood by my side,” Bass said in a taped interview related to his election. “When I had a slow start, he turned me over to Namiki-san. When a pitcher would throw the ball six inches outside, the umpire would say, ‘That’s a gaijin strike.’ So I had to learn how to hit that ball or I was going to strike out a lot. Namiki-san showed me how to hit the ball to left and center. Once it started clicking, I became a dangerous hitter.”

Ramirez recalled that “One of the things I thought [at first] . . . was, ‘I’m coming from the major leagues, so I’m coming to teach the game of baseball,’ but Japanese baseball is a totally different game . . . so it was very hard in the beginning . . . [and] I needed to change my mind into Japanese baseball and not [be] thinking Major League Baseball.

“When I started my career with Yakult, it was very special. I struggled early, and if I hadn’t started in Japan with someone like (then-Swallows manager Tsutomu) Wakamatsu, I wouldn’t be in the Hall of Fame today,” Ramirez added, who also provided a Hall of Fame first by listing his interpreters and assistants over the years by name in his speech.

“[In the beginning], I wanted to go to Japan, make good money, play baseball a year or two, and come back to the minor leagues or the major leagues, but I fell in love. I fell in love with Japan, and the way the Japanese people treated me was number one. This was the place for me.”