One thing documentarian Yuriko Gamo Romer knows above all about the filmmaking process is that one never knows where the path will lead.

“Anybody who knows anything about documentary filmmaking knows that you start with an idea, but then the project often goes in different directions,” she says with a laugh.

And she has personal experience to back the claim – an idea that began as a mini-project, gradually morphed into a not-yet-completed maxi-project, and then birthed a separate mini-project.

A baseball fan and award-winning filmmaker, Gamo Romer set out in 2014 to make a documentary about the 1949 tour of Japan by an American all-star baseball team headed by Japanese-Baseball-Hall-of-Famer and San Francisco native Lefty O’Doul. With World War II having ended just four years earlier and hard feelings still on both sides, the goal of the tour was to help ease tensions, and it was regarded as a rousing success. However, Gamo Romer knew little about it until Dave Dempsey, a friend and the son of a pitcher on the team – former San Francisco Seal Con Dempsey – told her his father had taken some home movies during the tour.

“I thought the 1949 tour was a great subject and that I could make a little film about it,” she said, “but I started doing all this research and steadily learned more in bits and pieces.”

She realized that baseball had been introduced in Japan long before, in 1872, and that there had been many tours of Japan by various American teams from the amateur, collegiate, and professional ranks beginning in the early 1900s. In addition, she found a rich history of Japanese Americans playing the game in the United States, both pre-and post-World War II. The more she learned, the greater the scope of the project – called Diamond Diplomacy – became. So much so that she’s still working on it nine years later with the hope of completing it next year.

Built around the baseball stories of former players Masanori Murakami, the first Japanese to play in Major League Baseball when he pitched for the San Francisco Giants in 1964 and 1965, and American Warren Cromartie, who played eight seasons in Japan, Diamond Diplomacy will examine subjects such as racism, international relations, and the influence of sports.

“The project was way bigger than I had originally anticipated. We’ve started editing, and I’m doing all I can to keep that moving,” Gamo Romer said. “We have a little more filming to do and need to come up with a big chunk of money to do that.”

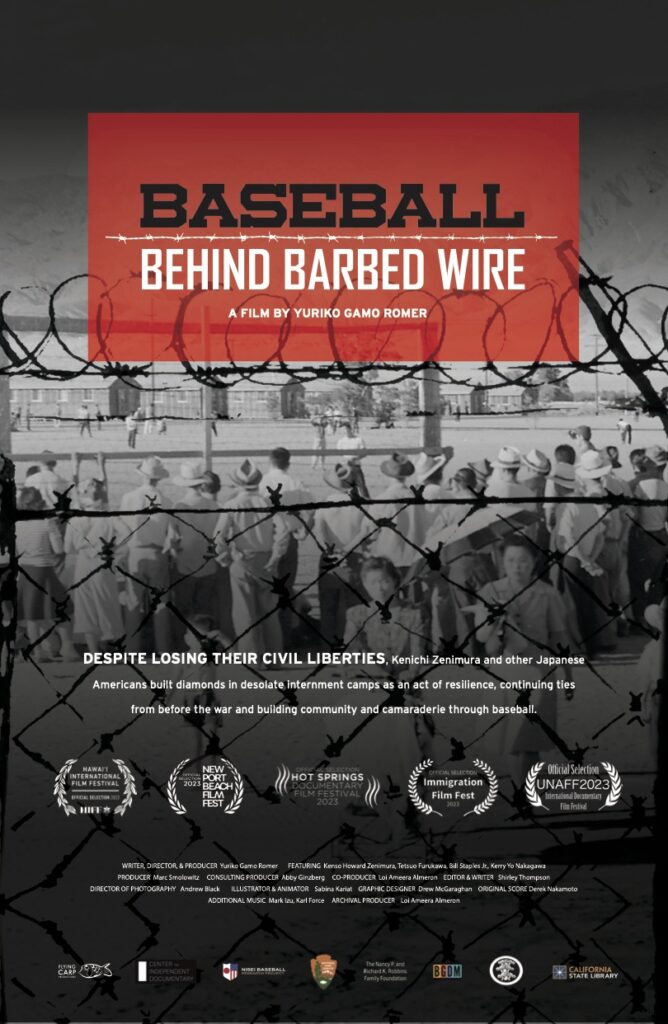

But though the overarching project is ongoing, the effort resulted in material and inspiration for an excellent, enlightening short documentary, Baseball Behind Barbed Wire. The film is about the incarceration of Japanese Americans in the United States during World War II and how they leveraged baseball to keep going through an extremely difficult period.

One of Gamo Romer’s sources for Diamond Diplomacy has been Kerry Yo Nakagawa, who is the son and grandson of camp internees. According to the film, his father was the town plumber at the camp in Arkansas. Nakagawa is the founder and director of the non-profit Nisei Baseball Research Project (NBRP), the mission of which is to bring awareness and education about the incarceration through the prism of baseball. He is also a filmmaker, writer, and historian; amongst his many projects are the books Through a Diamond: 100 Years of Japanese American Baseball and Japanese American Baseball in California: A History, the films Diamond in the Rough and American Pastime, and a traveling exhibit of Japanese American baseball that has been featured at the baseball halls of fame in Cooperstown and Tokyo, as well as the MLB All Star Game.

“I’ve known Kerry Yo for a long time, and he has tremendous passion for focusing on Japanese baseball in America and also the incarceration,” Gamo Romer said. “He’s been the main historian for the film. It’s not a totally new idea – there have been films about the incarceration, including ‘Diamonds in the Rough” – but I’d never seen anything about it from the baseball standpoint, at least not intrinsically about baseball. At any rate, we got some grant money from the National Parks Foundation in 2020. Though we couldn’t do much filming then because of Covid, we were able to do a lot of archival research. And once the Covid lockdowns ended, we could really move forward.”

The 34-minute film is now being screened in the U.S. Its world premiere was earlier this year at the Hot Springs (Ark.) Documentary Film Festival, and it has also appeared at the Hawaii International Film Festival, the Newport Beach (Calif.) Film Fest, the Immigrational Film Fest in Washington, D.C., during a symposium at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y., and at three schools in Wisconsin where Nakagawa had previously spoken. Most recently, it was shown in late October at the United Nations Association Film Festival in Palo Alto, California.

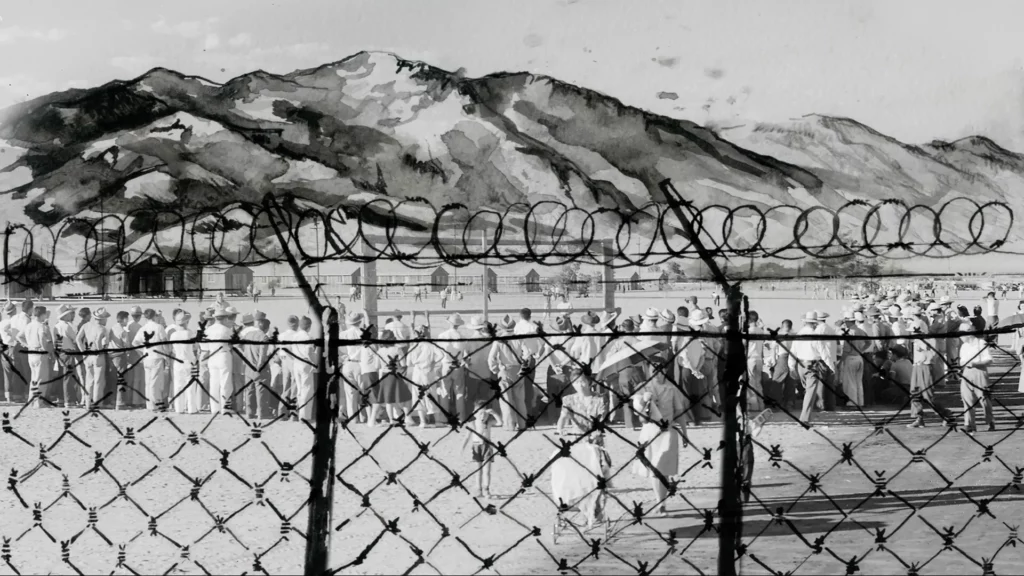

The film focuses on how the internees used baseball to help the make the best of a bad situation. As the film’s website notes, “There is great irony in the popularity of the all-American sport of baseball being played by Japanese Americans during WWII incarceration,” which began when President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942.

The order affected approximately 120,000 people on the West Coast of the U.S., who were arbitrarily assumed to be security threats. The documentary tells of one family that used an outhouse located behind the living quarters. The family members had to turn on the light when using it at night. The authorities, however, concluded that they were using the light to signal Japanese submarines.

Internees moved first into temporary housing and then to hastily built facilities that offered little in the way of protection against very hot summers and very cold winters. There was also little to no privacy regarding toilets and shower areas, robbing the internees of their dignity. The documentary shows photos of open lines of toilets and showers, and there is one gripping picture of a child using the toilet and holding his head in his hands.

Nakagawa reports that when people first went to the assembly centers, “they stayed in the animal stalls for six months, and . . . even though they took water hoses [and] fire hoses to wash out the manure [of] the farm animals, imagine the stench and the smell from the summer all the way to December.”

In the film, Nakagawa also remembers that, after the death of his grandmother while in the Arkansas camp, her body was sent to a facility in Mississippi for cremation. The ashes were returned in an old Folger’s coffee can with a slip of paper on top coldly stating “Jap Woman.”

Gamo Romer acknowledged that the details she learned and the testimonials from the incarcerated were often uneasy to deal with, but “they’re important for the credibility and impact of the film.”

However, though the Japanese Americans were detained and denied their citizenship and civil rights, playing baseball provided some sense of normality, even though they played while under the watchful eyes of armed camp guards and hemmed in by barbed wire.

The film recounts how internee Kenichi Zenimura overcame his initial depression at being sent to the Gila River camp in Arizona by deciding to laboriously build a baseball field from scratch in the desert with the help of his two sons and some other avid young players.

Zenimura, who passed away in 2018 at the age of 91, said, “One of the things that [was] really hard was trying to get water into the area . . . We dug a trench all the way to the laundry room, and a person in camp [who] was a plumber connected the pipeline to the laundry room. We [had] to do it during the night when nobody [was] using the facility. What we did was shut down the mainline and connect [it to] the pipeline, and that water was sent all the way to the back of the pitcher’s mound.”

They used flour to chalk the foul lines and even built stands and dugouts using scrap lumber and old fence posts, some of it pilfered.

According to Zenimura, “The lumber yard was way on the other side of the camp, probably a mile away. We’d go out there in the middle of the night, get lumber and lug it all the way out into the sagebrush, bury it in the desert, and then go back later and get it as we needed it. The camp officials probably knew what was going on, but nobody said anything.”

Another incarceree, 94-year-old Tets Furukawa, noted that the March 7th, 1943 opening of the field was a very significant day for those in the camp “because this [was] America. We [got] to play baseball again. We didn’t have hot dogs or Coca-Cola, but we made the best of it. The camp director was invited, and he threw the first pitch. We had a doubleheader that day. So, it was just like America again.”

Baseball spread to the other nine camps, some of which had multiple fields and as many as 30 teams participating, and teams from different camps eventually were allowed to travel and compete against each other. Women made uniforms out of things like old produce sacks, used clothing, and deconstructed mattress ticking. Some wrote to their Caucasian friends back home, asking them to ship their former team uniforms to them.

Zenimura also used baseball to begin breaking down racial barriers, eventually setting up games against non-Japanese clubs. The film shows how, in 1944, the Gila River all-stars played the Tucson Badgers, a team that had won the Arizona state championship two years in a row. The first game was at the camp and was tied 10-10 going into extra innings, and then Zenimura doubled with the bases loaded to win it. The second game was to have been in Tucson, but the local people rallied against it and forced cancellation.

The executive order was rescinded in December 1944, and the camps were closed in 1946, leaving the former internees to put their lives back together after having lost jobs, property businesses, savings, and more. They did, and baseball continued to be a constant through it all.

Gamo Romer’s goal is that Baseball Behind Barbed Wire will increase awareness of the World War II incarceration and also of the rich history of Japanese American baseball. At the moment, there are no other showings scheduled at festivals, but she hopes to have it screened elsewhere in the San Francisco Bay Area in February since that will mark the anniversary of Order 9066.

“We will have educational distribution through Good Docs,” she said. “We really want this to go into schools and have the kids learn about it. [Baseball is] an interesting side door into the subject [of the incarceration]. Also, California has an ethnic studies mandate for high schools, and I’d hope this would be a part of that. Eventually, I’d like it to be on PBS or something similar – a broader distribution. Got to meet some public television people in Hot Springs, and maybe those contacts will eventually prove to be fruitful.”

Some have suggested that this could be the start of a series of short documentaries arising from the Diamond Diplomacy project, but that would be for later down the road.

“I’ve been asked that by some people,” she said. “There are potentially other things that could come from it, but there’s nothing specific at this point, and we’d have to get a big chunk of money for that to happen.”

Click here to learn how to support Diamond Diplomacy.

In addition to Gamo Romer (director/producer), credit for this documentary is also shared by:

- Marc Smolowitz (producer)

- Abby Ginsberg (consulting producer)

- Loi Ameera Almeron (co-producer)

- Shirley Thompson (editor)

- Andy Black (director of photography)