2020 was the official celebrated centennial of the Negro Leagues, a group of professional baseball leagues that hosted the greatest Black ballplayers in America before Major League Baseball’s integration in 1947. While many celebrations were put on-hold due to the COVID-19 pandemic, much discussion has still taken place this year about the Negro Leagues, and their role as a whole in professional baseball, even across the seas in Japan. On Nov. 19, Bill Staples, Jr. joined “Chatter Up!” to discuss the topic, along with his book “Gentle Black Giants: a History of Negro Leaguers in Japan.” You can check out a recap of the discussion here, or also the full video on our YouTube channel! If you’d like to read Staples’s book for yourself, please purchase it on Amazon via our affiliate link.

Shane:

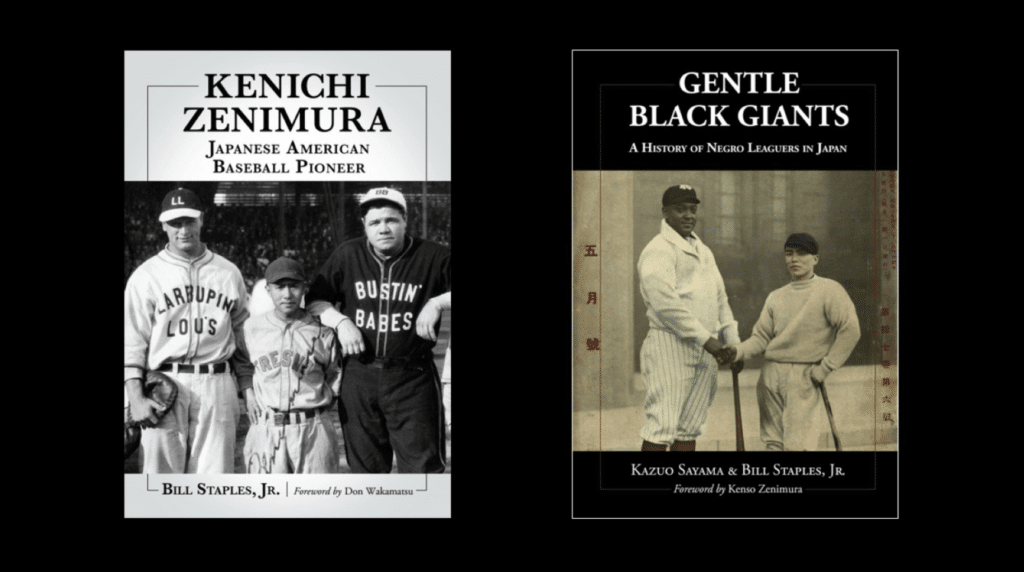

All right, Bill, I’m just gonna put you on the spotlight here for a second so everyone can see you. Hi Bill, welcome. So, let’s get to introducing Bill Staples Jr, our guest. Bill is joining us from Chandler, Arizona, where he lives with his wife and two children. He was born in Troy, New York, raised in Plano, Texas, a self-described Yankee Texan living in the desert. [He] studied advertising and journalism at the University of North Texas, and earned his MBA from Arizona State University. His day job is Marketing Communications in the IT healthcare industry. But, of course, the reason he is here is that he is a baseball author and historian. He claims to have inherited the baseball bug from his great grandfather, Merritt Corbett, who played professionally over 100 years ago, and played against many of the great Negro League stars of the day, of the first decade or so of the 1900s. Of course, he’s the author of “Gentle Black Giants,” the subject of today’s talk, but he’s also the author of “Kenichi Zenimura, Japanese American Baseball Pioneer,” which is the winner of the 2012 SABR Baseball Research Award. Speaking of SABR, he’s the chairman of the SABR Asian Baseball Committee, which I believe is founded by Rob Fitts, who’s on the call with us today. So he’s continuing Rob’s legacy there. Bill’s also a board member of the Nisei Baseball Research Project, the Arizona chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League, Research Contributor to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, and he’s presented at the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, amongst other places. Bill offers his time, persistence, research expertise and knowledge to many national and local projects that benefit his local community, and the greater Japanese American and African American communities. So for those, we thank you. And we also thank you for spending time with us tonight, Bill.

Bill:

Great. I was going to give the 20 minute conversation, and then we’ll open it up to Q&A. I’d like to give 10 minutes or so to my time to a guest. He doesn’t know that I’m going to invite him to speak, just because Ralph Pearce is with us tonight. And Ralph contributed a great section on Jimmy Bonner, first African American to play over in Japan, at least professionally, to sign a contract. So if he has some time, if you’d like to share, we can spend five to 10 minutes on Jimmy Bonner. So Ralph, just want to give you some kudos and recognition since you’re here.

Shane:

Yeah, that’d be great. And Ralph, thank you for joining us.

Bill:

Okay. All right, everybody, thank you for your time this evening. So we are here to celebrate the Negro League Centennial, and I’m going to talk about “Gentle Black Giants: a History of Negro Leaguers in Japan.” So with that, just an overview of what we’re going to cover. I want to provide a background of the inspiration for this book and how I got involved, and also my interest in Japanese baseball and Japanese American baseball, and Negro League history. I want to talk about the process that I went through to develop the book, because it was a team effort, and then I’m going to share some highlights because I imagine not everybody purchased the book. So I’ll share probably about three or four pretty cool highlights from the book and then we’ll open up for Q&A. So a little bit of my background. As Shane mentioned, I’m the author of two books. The first one is “Kenichi Zenimura, Japanese American Baseball Pioneer,” it’s about Kenichi Zenimura, who I met kind of virtually when I moved to Chandler in 2004. So I live right next door to the Gila River Indian Reservation and Community. I’m a youth baseball coach, and I was in Texas before I moved here to Arizona, and I thought it’d be great to give to the community and coach on the reservation. So I did a search for Gila River in baseball. Nothing popped up with regards to coaching opportunities. But all this great information from the Nisei Baseball Research Project about Kenichi Zenimura and his great career. And I’ll talk a little bit more about that later. But I thought I knew a lot about baseball history, but I didn’t know anything about Japanese American history, and it reminded me a lot of the Negro League story, that these are great ballplayers who were forced to play in leagues of their own because of the discrimination and racism of the year in which they grew or lived in.

So in a sense, my joke is that “Kenichi Zenimura” is my “Star Wars,” and “General Black Giants” is my “The Empire Strikes Back.” It’s an extension, it’s part two of this story, because Zenimura influenced the tours of the Gentle Black Giants, or the Philadelphia Royal Giants, because of his relationship with the team in the 1920s. So it does all start with Zeni (his nickname) and his relationship with Lon Goodwin. So Lon Goodwin was the manager of the Philadelphia Royal Giants. He’s from Austin, Texas, and because I was raised in Texas, there’s a lot of cool Texas connections that I’ll point out. But he was born in Austin, Texas in about 1879, moved to California. This story is really important because not a whole lot of recognition is given to West Coast Negro League Baseball, and Lon Goodwin’s a very important figure in West Coast Black Baseball history. He was a teammate of Rube Foster, with the Waco Yellow Jackets in the 1890s, and around 1920, he actually signed a Japanese American to play on his all-Black team, which is pretty rare. But there was some marketing involved as well, because he was trying to draw the Japanese American community to come buy tickets and watch his team play. So in 1925, Zenimura competes against Lon Goodwin’s team called the LA White Sox. That’s the first time they play Zeni’s team, the Fresno Athletic Club. They win 6-5, by one run, surprised everybody. The next year they have a rematch with a doubleheader, Fourth of July Weekend, 1926. One thing I should mention, Zeni had already had his first tour to Japan in 1924, so he was well connected in Japan, and one of his important partners, if you will, in arranging baseball tours, is now in Japan, attending major university; his name is Frank Narishima, or his Japanese name was Takiza Matsumoto. So, anyway, 1926, Zenimura spends a weekend with the LA White Sox. They have a doubleheader, Zenimura’s teams win both of those. But by December, the LA White Sox are invited to come and compete in Japan. That’s an important distinction, because the LA White Sox were invited, but it’s the Philadelphia Royal Giants who end up going. Lon Goodwin changed the name of his team late 1926, and he took his California Winter League team to Japan. So that’s the Zenimura connection in terms of the LA White Sox and the invitation to go to Japan.

Shane:

Do you know why he wanted the Philadelphia Royal Giants?

Bill:

Well, on paper, they were a stronger team. So I think from a marketing standpoint, he probably could have had a better draw. His intent was to actually take the entire California Winter League roster, which are all really the top all-stars with the Negro Leaguers, who went to the West Coast to compete. Turkey Stearnes was part of that lineup, maybe Bullet Joe Rogan and the 1927 team. Some really top notch names, but only four of those players ended up going: Biz Mackey, Rap Dixon, Frank Duncan, and Andy Cooper. All four of them ended up getting in trouble with the Negro League officials, because they skipped their contract and showed up about halfway through the season. They were supposed to be banned for the entire season, they ended up paying $100 or $200 and just kept playing. So they had a lot of weight, if you will, and they wanted to get paid and they made more money in Japan than they would have if they stayed in the US.

So this is the original cover of “Gentle Black Giants” published in 1985 by Kaz Sayama, and this is the new cover. But I wanted to talk about this photograph here. I joked with Rob that this was Biz Mackey and some unknown Japanese ballplayer. So around 2006, I get into this research, and I’m working with the Negro League Baseball Museum and they send me this photograph, because Rob, I believe they purchased one of the magazines that was for auction at the time, so they were trying to figure out who it was on the cover. So working with Professor Kyoko Yoshito over in Japan, we went through this kind of photo search and tried to match it up. And we identified that it was O’Neal Pullen, who’s kind of an unknown Negro Leaguer from Beaumont, Texas, and a Hall of Famer from Japan, Shinji Hamazaki. So we kind of got the story right, that it was an unknown player and a Hall of Famer, but the other way around. So we’ll talk more about Hamazaki as we go through telling the story.

Kaz is not with us tonight. So I thought I’d take some time and introduce him to those who may not know him. Huge baseball fan, he attended baseball fantasy camps, actually a lot like I did, I spent a five year career going to Florida, and playing ball there and had a great time. But my eyes are fading and I can’t see the ball moving anymore. He’s going to be 85 this year, as you can see from this slide. His favorite sports are baseball and swimming, and his goal in life is to write good stories, which is a great goal, and he does do that. He did that with “Gentle Black Giants.” So I want to get the background of how he became inspired by this story. So he is a SABR member in 1983. He traveled all the way from Japan to attend the SABR conference in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He’s good friends with Clifford Kachline, I believe his name, he was the librarian with the Baseball Hall of Fame up in the top there. Clifford introduced him to John Holway, one of the top Negro League historians at the time, and still is well respected. And John approaches Kaz and says, “Hey, I need you to tell me as much as you can about the Kansas City Monarchs going to Japan in the 1920s.” So in John’s mind, he thinks it’s the Kansas City Monarchs, because it’s Frank Duncan and Andy Cooper, who played for them. But it wasn’t the Monarchs that went, we now know it was the Royal Giants. Kaz was kind of like me, he thought he knew everything about Baseball History in Japan, but didn’t know anything about Negro Leagers going to Japan. He only knew about Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig and those famous Major League tours. So he gets the bug. He’s got the passion to really research the story. And my joke is that he kind of reminds me of Ray Kinsella in Field of Dreams. So I envision him like with his passion, doing all this research, trying to find out all he can about these players. So he interviews all the former players… not all of them but some of them. He goes to nursing homes, talks with some of the old players and umpires who played against the Royal Giants, goes to the Hall of Fame, unearths a lot of research, goes to the archives. Then he gets on a plane and he travels to the US, goes to the Hall of Fame here, interviews Roy Campanella, Monte Irvin, Leon Day, anybody who played with Biz Mackey, because Biz passed away 20 years ago. And then he learns that Phil Dixon has Bullet Joe Rogan’s passport. So he’s got to go visit Phil Dixon, which is kind of a pretty interesting story there.

He publishes just an article in SABR’s Baseball Research, and it was called “Their throws were like Arrows.” He introduces the Royal Giants to an English reading baseball audience. But years later, Kaz tells me as we’re finishing the story the true inspiration as to why he really wanted to write it. So he tells the story of when he was a kid. He said, “When World War Two ended, I was a third grader in Wakayama City. American soldiers soon arrived, and they were especially kind to us kids. I later learned that they were members of the all-Black 93rd Infantry Division of the US Army, and like us, they loved baseball, and some even coached and umpired at our games. And one day, one of the soldiers said to me, ‘someday you’ll be a great pitcher.’ Sadly, I never did fulfill his prophecy, but his encouragement fueled my love for the game, and I became a baseball writer instead.” So “Gentle Black Giants” is my thank you letter to that soldier. So it came from the heart, Kaz, in why he wrote this. And one of the things that I really liked about when he told me this, two things: the 93rd infantry, they trained at Fort Huachuca here in Arizona, so it’s probably just three miles from my home right now. And they played ball in the 1940s on Rube Foster Field. It’s probably the only ball field that was named after Rube Foster. And it was in the middle of the Arizona desert, down near the border. So it’s kind of cool that it kind of comes full circle, and especially nice that we’re celebrating the Negro League Centennial with Rube Foster and what he did.

So now I want to share my personal connection. This is me and my family, and that’s my mother-in-law on the far right, her name is Dorothy Ross Newman. Her great uncle is Robert Bailey, and he played in the Texas Negro Leagues. He played in the 1919 Texas Negro League Championship. O’Neal Pullen was his teammate playing catcher, Bob Bailey’s playing second base. Will Ross is the pitcher, and Biz Mackey’s playing on the other team with the San Antonio Black Aces, normally the Black Broncos; this year all the teams changed their name to honor the returning troops, so they’re all military names. And Dorothy before she passed, she asked me to try to write Bob Bailey’s story, but there’s very little out there on Bob Bailey. So this is in a way my personal attempt to kind of pay tribute to him and the Texas Negro leaguers and all of his teammates and what they did, and the impact they had on baseball in Japan as well. So I just wanted to share that.

Finally, one of my favorite ballplayers and maybe everyone here who loves Japanese baseball, Sadaharu Oh. He says, “My baseball career was a long, long initiation into a single secret that at the heart of all things is love.” I think of his relationship with Hank Aaron, and it also reminds me of the spirit in which the Gentle Black Giants approached their games with the Japanese ballplayers. And in that same spirit, I wanted to help bring this book to English audiences. So anyway, that’s the background and the inspiration.

So now I just want to talk about how I got to know Kaz just quickly in 2011. I’m doing a little book tour here in Arizona. I meet Perry Barber, the umpire, and she buys two copies of my book, one for her, and one for some guy in Japan named Kaz Sayama, and so he gets my book and we start connecting. He’s doing some research on the 1935 Nipponese, or Japanese All-Stars, who play in the Wichita tournament in Wichita, Kansas. So it’s Kenso Nushida, and some other All-Stars from Northern California. So I help him do the research, and he’s thankful. So he sent me a copy of his book, Gentle Black Giants. And all I could do is look at it in salivate. I couldn’t read it. I can’t read Japanese Kanji, and I can’t speak it, I know some basic terms. But I really wanted to know what was in this book and other historians around me were saying, “God, it’ll be really great if somebody could translate it.” So after a few failed efforts of trying to get volunteers to do it, I realized I’ve got to pay some people some money to do it. So I did a little fundraising in the local Arizona Japanese-American community, and were able to raise some money for the translation project. So the Japanese American Citizens League, the Nisei Baseball Research Project, and the Japanese business community here in Arizona, helps fund the translation. So in turn, this book is really kind of a fundraiser for these two nonprofits, and the Negro League Baseball Museum, for any of the research we do for them.

What’s kind of cool about the Japanese American community being involved is that historically, they’ve always played an important role in building that bridge, if you will, between the US and Japan. So in the 1927 tour, George Irie played an important role as the translator, and the organizer, if you will, for everything for the team over in Japan. And then in 1932-33. We have Steere Noda from Hawaii, who serves in that same role, translator and interpreter. He’s very interesting because in the 1950s, he eventually becomes an important politician, and he helps with the State of Hawaii. If I’m not mistaken, I believe he may have been one of the first representatives from Hawaii as well.

All right, quickly go through the process that we went through. I hired two translators: Shimako Shimizu here in Phoenix, she helped with the original Japanese to English translation. I served as the editor, cleaned it up. And then I had another Japanese reader translate it back to the book to compare. Then from there, we cleaned it up. And Gary Ashwell, great Negro League historian, great editor as well, Kerry Yo Nakagawa proofed it, checked it. And then we worked with the Nisei Baseball Research Project to develop it. Just a few editorial decisions that we had to make along the way. This great article from 1986, I believe it was that Kaz wrote, that kind of serves as the model for his English voice. But at the same time, I wanted English readers to be reminded that they’re reading the perspective of a Japanese author. So we kept the Japanese years in relationship to the Emperor years, if you will, Showa 2, 1927, Showa 9 1934. So as you read, you’ll see those. And then there was for my comfort and preference, there was an excessive amount of just the phrase, “the Black team: the Black team did this, the Black team did that.” And so they had a name, it’s the Royal Giants. So that was my decision to mix it up. And to make it a little bit easier for our 21st century ears and eyes when reading.

Basically what the project ended up being is two books in one. The first part is the English translation to Sayama’s “Gentle Black Giants,” and then the second part is a history of Negro Leaguers in Japan, which is really, as Rob was saying early on, great appendices of a tour scrapbook, newspaper clippings, photos, maps, a lot of stats. Actually, Appendix A is a list of every tour between the US and Japan, from 1905 to 2019, all different levels, college, high school, Semi Pro, professional, etc. I said “Oh, we’ll put an asterisk by the list, we probably missed a few. But we’ve got control of the press and we’ll update when we need to. So when stats were available, we included that, player bios, and all these great articles from other historians have done work on African Americans over in Japan. Dexter Thomas, Ralph Pearce, who is with us tonight. Kyoko Yoshida and Bob Luke wrote a great biography on Biz Mackey.

Robbie:

Just to be a pain in the ass. I found a tour you missed a few minutes ago.

Shane:

Was he talking about the JapanBall tours he missed? He didn’t fit those in there.

Bill:

You know what? You guys want to sponsor the book going forward? Get the price down to $9.99 for everyone?

Shane:

Yeah, I like that.

Bill:

So then it came time for the foreword. Don Wakamatsu wrote the first one for Kenichi Zenimura, I thought it’d be nice to have a Major League manager with some personal connections, reached out to Dave Roberts and his team; his mother is from Japan, his father’s African American from Texas. He passed. Then I thought it’d be interesting to have [Sachio] Kinugasa in Japan, the Iron Man of Japan. But there was a lot of hoops involved, and unfortunately, he was not well by the time we got there and he passed away in 2018. Then I realized I had an obvious choice right on my speed dial. I call Kenso Zenimura about once a month since 2006, 2007. He was born in 1927, during the first tour. I’m going to share something really interesting here. And then in the 1930s, he grew up in Fresno, California watching these guys play on the West Coast, when they would come to his dad’s ballpark, the Japanese ballpark in Fresno. So anyway, I reached out to cousin Kenso. Here’s the other cool thing I wanted to share. Kenso Zenimura is the second name to the end; je’s on the same passenger ship in the summer of 1928 with O’Neal Pullen; basically the whole team going to Hawaii. So the Zenimura family is going to Hawaii at the same time, they’re on the same ship together with O’Neal Pullen’s summer team going to Hawaii. So anyway, I reached out to Kenso, and he wrote it. And I’m glad that he did, because sadly, he passed in December of 2018. So it’s a nice way to remember him. And his connections are really interesting. Side note, he helped build Zenimura Field here in the internment camps. And he got out of the camps in 1945, the summer of ‘45. He moves to Chicago to live with his uncle. And they go to the Negro League All Star game at Comisky Park, he got to see Jackie Robinson playing second base for the Kansas City Monarchs in that game. It was one of the highlights of his young career. But he would later go on and be one of the first three Americans to play for the Hiroshima Carp, him and his brother Kenshi and Ben Mitsuyoshi, all from the Fresno or Central California area.

So the book title is “a History of Negro Leaguers in Japan,” but it’s actually a misnomer, because it’s really in Asia, and in the Pacific, because it’s more than just Japan, but that would have been too much for the title. So it’s Japan, it’s Korea, it’s China, it’s the Philippines, and it’s the Hawaiian territories, which it was referred to as during the 20s and 30s. There’s so much confusion prior to sitting down and really buttoning things up, about when they went, where they were during certain years. So that was the goal in this project as well, is to know exactly which tours, when they started, when they ended, how many games they played, where the dates, of course, how far they traveled, etc. And at the end of the book is a compilation. We recognize six tours, three of them to Japan and China and Korea, and then three to Hawaii only. So 1927 is Japan, in Korea and China, ‘28, ‘29, and ‘31 are only the Hawaiian territories. That may not seem that important, but it was actually a middle ground in a meeting place for teams from Japan. So when we talk about building this bridge to the Pacific, that was a very important midpoint, in that relationship. Then the Winter of ‘32-‘33, then ‘33-‘34 were the more extensive tours. I added it all up and the total of number players, 44 players, one manager and the two promoters that I mentioned.

So a couple of things that I learned along the way. There’s this concept in the Japanese American community, I believe it’s consistent in the Japanese community as well: Honne and Tatemae; the inner truth in the outer face. So keeping harmony within the relationships is very important in these communities. And I found that perhaps a lot of what was shared historically about the tours was kind of the outer face, trying to maintain harmony. And as we were translating Sayama’s book, I realized we were starting to see some inner truth, that these Japanese ballplayers were starting to share their experiences and observations, about the attitudes and behaviors, and comparing and contrasting the Black teams with the all-white teams. It was very eye-opening. So I’m going to share some of that with you here.

So Chapter 17 of Kaz’s Gentle Black Giants. He has a really interesting comparison of Team A and Team B. And Team A is the All-Americans and Team B is the Royal Giants. And so we put it into more of a table format here, but in the text that’s pretty consistent with how he had laid it out. So everybody knows about Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig and the All-Americans: they played 34 games. Kaz recognized that the Royal Giants played 48 games. They were well-known white players, compared to the unknown Black players. Team A, they were sponsored by local or the newspaper there in Japan, whereas the Royal Giants, they were self-funded. The All-Americans arrived with this attitude of “Hey, we’re the experts. We’re going to show you how to play,” whereas the Gentle Black Giants, they said “We are friends, let’s play ball together.” There are stories of times where the All-Americans changed the calls, or ignored what the umpires were saying in Japan, whereas the Black players were very respectful to the umpires, bowing in certain situations. The All-Americans ran up the score, the Royal Giants kept the games very close. After the games, the Japanese players were very disappointed and frustrated, and some of them said they were going to quit, whereas with the Royal Giants, after the games, the Japanese players gained confidence in their skills. The All-Americans returned to Japan, some of them were disappointed with their experiences, whereas the Royal Giants, they loved being in Japan. In fact, they were treated like kings in Japan, compared to how they were treated here in the US. Then Kaz’s final point is that we’ve heard so much about the All-Americans, and from his perspective, and he was the first one to basically unearth this, nothing has been said about them for half a century, or for 50 years. And again, this is 1985 when he first found this. So a really interesting and insightful compare and contrast between the two tours. Again, from the perspective of the Japanese players and the umpires and those who were involved.

Shane:

Bill, I have a question. The book clearly points out how culturally, and based on the hospitality, why the Royal Giants were so respectful as guests and how they appreciated their reception, and it was a pretty mutual feeling. But it also alluded to the financial aspect, and the business incentive to behave in a way that was far different than the Major League players behaved. Like how much of that is business influence? And how much that is cultural influence?

Bill:

Well, this is just me guessing. Yeah. With some business influences, but I mean, it’s marketing, they want to maintain good relations, they’re relying on people coming out to the ballpark, being respectful to their guests. If I had to guess I’ll throw a percentage out, it’s probably 80-20. But for me, I think it’s the idea of doing the right thing and treating their guests with respect, but then being mindful that they’re there to make money and pay for the trip. So that’s my take. Other people may have a different assessment. Baseball people are very opinionated. So we’ll see how it goes.

Shane:

Yeah, I definitely got the impression that it was something like that, it’s interesting, there’s multiple incentives. It’s interesting how they didn’t have any guarantee of games in a lot of cases, so they had to make sure that they were making a good impression. And they were extremely successful and savvy at that, but largely because it came so naturally, and they have been good sports about it.

Bill:

Yeah. I’m gonna play the Texas card here: actually, the bulk of these players didn’t come from Texas. AJay Johnson, the pitcher, O’Neal Pullen, Biz Mackey, Andy Cooper. However, my mother-in-law’s saying: “Act like somebody loved you, or raised me with love.” So there could be some of that, just bringing in how they were raised and how they’re going to interact with their guests. So it’s being gentlemen, if you will.

So how does that translate into the dynamics in the game experience? So as I was doing the research, and the writing for this book, I’m working with a trainer, whose background is in Aikido. And he starts sharing this concept with me called the Uke-Nage relationship. And it’s basically kind of this agreement between the sensei and the student that the teacher is not going to exert full force, they’re not going to kick their butt, so that the student can enjoy the learning process, stay encouraged and still develop and learn and grow. And as I was thinking about that, and I also thought about when he said, Aikido, I thought about Sadaharu Oh, and his relationship with his master in Japan, Arakawa. I thought there was some of that dynamic as well, from what I remember reading in his book, “A Zen Way of Baseball.” So I think that the spirit of that kind of relationship existed between the Gentle Black Giants and the Japanese ball players that they competed against as well. Kaz kind of refers to that, he called them the shock absorbers. He said, “Other countries rejected baseball because the visiting professionals left fledging players disillusioned with the game through defeat. But we were lucky enough to have a chance to neutralize that shock: The Royal Giants’ visits were the shock absorber.” This is where the controversy comes in, because there’s a lot of generalizations about some of the things that Kaz says about the influence of the Gentle Black Giants. Some people have read what Kaz has said and said that he inspired the start of Pro Baseball in Japan. Well, if you really get into the nuance of what he was saying, it was really about that dynamic and that relationship and developing the players, but really about the timing, as well. So this quote right here captures that.

“Baseball has many elements that appeal to the Japanese mind, and it may safely be said that professional baseball would have been born in the course of time. Without the visits of the gentlemanly and accessible Royal Giants, however, I don’t think it would have seen the light of day as early as 1936.” So Kaz’s argument is that it was the right people at the right time, the stars were aligning so that professional baseball could start in the mid 1930s. Again, these tours are 1927, ‘32, ‘33, ‘34. This is kind of my reconciliation with all of that, thinking about baseball as a business.

For any business to succeed, there’s a certain supply and demand in economics. And there’s no denying that the influence that the All-Americans had in building that excitement around professional baseball and the hunger for it, I think that’s where the All-American tours get a lot of credit for: their influence. But from the supply side, helping the players develop and encouraging them, so that they were in the right mindset and the right skillset to then start professionally. I think some credit needs to be given to the influence of the Royal Giants as well.

So I just want to end with kind of an overview of the skill level of these players. So it’s a very interesting blend of Negro Leaguers, and Cuban League ballplayers who are Hall of Fame caliber, Major League caliber, and then a mix of semi pro players from California. So you have this wide range of being able to turn on the throttle and turn it down, which allowed them to kind of control the score and keep things close, which is a really good formula for that dynamic. Unlike the All-Americans where it was- Shane, like you referred to- the Dream Team of ‘92 in basketball. So the Hall of Famers who were involved, Bullet Joe Rogan’s in the Hall, Andy Cooper, Biz Mackey. I personally think maybe Rap Dixon and Chet Brewer are the next two players to go in. And I became very impressed with the career of Lon Goodwin throughout this process, I think he’s very influential in terms of West Coast baseball, all the tours that he helped inspire, influence and arrange. I introduced this concept called Transpacific Barnstorming, just like the mainlanders who got in the bus and drove around the US. These guys are barnstormers too, except they got on a ship, and went all across the Pacific, which is really impressive. And again, Lon Goodwin’s tied with Andy Cooper, when you look at the cumulative number of days on tour of the total tours, so again, very impressed with the role of Lon Goodwin. And I think this is my prediction, a couple decades, he’ll get more recognition for his influence.

And then quickly, I’m going to just zip through some highlights. So it’s very interesting when they first arrived, the Royal Giants. The Press accidentally referred to them as a Native American team. So there was this postcard that was floating around, “Indian Baseball Team Visits in Tokyo,” which is very interesting because in 1921, there was a Native American team that visited, I think it was the Suquamish Tribe from Washington. And I just learned in preparing for this that one of the Indian pitchers killed a Japanese player with a curveball that didn’t curve, much like the Ray Chapman situation. So Rob, that may be a story you want to look into.

The other highlights: Rap Dixon really put on a great exhibition of his skills. They would do contests, running around the bases; I wanted to offer some contemporary times, Billy Hamilton, Byron Buxton, Dee Gordon, you can see them. So he’s pretty equivalent up there with modern day ball players in terms of his speed around the bases, you know, 90 feet is 90 feet, and 360 feet, etc. He also had a great arm, he could throw the ball from home plate, I think 420 feet centerfield at Koshien, so [he] really impressed everybody there. Biz Mackey hit the first home run at Meiji Shrine Stadium, happened on April 20, 1927. Which by the way, that was the date that this book came out. I tried to match it up there. He also hit that ball off of the Fresno Athletic Club, so it’s interesting, there’s kind of two American teams competing in Japan. During the 1932 tour, Biz Mackey, forever the showman, he played all nine positions in the game against the Honolulu Asahi. He started off at catcher, worked his way all the way up to relief pitcher. And I haven’t been able to find other Negro League box scores that have a player playing all nine positions. I know what’s happened in the Major Leagues and you guys may know some of those players, but pretty impressive, really shows the multi athletic ability of Biz Mackey. By the way, his great grandson played in the NFL. His name is Riley Odoms, seen as a tight end for the Denver Broncos. His real name is Riley Mackey. And so Riley Odoms has his grandfather’s name.

Yuriko:

I want to back up a little bit. You were talking about the reception of the Negro League teams in Japan versus the All-Stars. Japan is not really known for its open mindedness about Black people or whatever. And so I’m kind of curious what you think about the fact that they were received so well, I mean, I think that there is a kind of hero worship thing about people who perform that well. I know that as much as Japan would have loved to beat the All Star team with Babe Ruth on it, I think they wanted to see him hit the home runs more than they wanted to beat the team. So as far as the Negro League teams, when they went to Japan, these are people that didn’t live like a very accepted existence in the United States. I wonder if by being treated so well in terms of the hero worship, part of being baseball stars, they had a unique experience? I’m not taking away from the sort of cultural thing of being Southern Gentlemen, but to have a completely different experience, and I don’t know how much of that came up in your research.

Bill:

Well, again, it’s a very interesting blend of ballplayers. I would actually call a lot of them, the semi-pro players in California, white collar players. So AJay Johnson, who is the pitcher, he went on to become one of the first African American lieutenants in the LAPD. John Riddle, he studied architecture at USC. He is one of the first African American running backs to play in the Rose Bowl in 1926, and so he went on and had a spectacular career in semi pro football, and then as an architect. So it’s an interesting blend, because most people think of Negro League players as kind of blue collar players as well. But that dynamic, I think, was balanced by some of those players from California. So I think just their own personalities and their backgrounds, some of them are well educated and professionals, I think that was important; they didn’t act like ballplayers. They acted professional, if you will, and I think that carried over. Now another thing that I think is very interesting: on page 44 of the book- this is probably one of the coolest things that came across in the translation- one of the Japanese ballplayers says “I can’t remember the name of the Black player who said it, but he said to me, ‘if a war ever took place between the US and Japan, we would cheer for you.’” The Black player saying he would cheer for Japan, and to the Japanese ballplayer. When they said that, they were saying “we’re a colored race too,” like they kind of felt like this tension. So one, that’s kind of an eerie prediction, 14 years before the war, but I think it maybe speaks to the kind of relationship between them. Rob, did you have something there?

Rob:

So there’s a whole literature out there that I discovered [when] I was writing my last book, about political connections between disenfranchised African Americans in the US and Japan during World War Two. And so there’s a lot going on politically there. So, all I can say is that it’s really complicated. And whether it’s because of the Japanese players’ perception of things, that particular players’ political perception, that, of course, was not completely shared by everybody, which is pretty obvious. But just something to explore someday. We can talk about it some other time, give you some pretty cool sources.

Bill:

Yeah. So W.E.B. Dubois, he traveled to Japan. Very important experience for him. There is just a fascination with African American culture in Japan, the John Coltrane museum is somewhere in Japan. Oh, and Dexter Thomas, who wrote one of the chapters in the appendices, that’s what he studies over in Japan, kind of hip hop culture fascination in the Japanese community.

Yuriko:

I think there’s a harder time with accepting the people who live there.

Bill:

Well, I can also speak maybe a little bit of personal experience. My wife’s family were military based in Tokyo, and they lived there for four years during the Olympics; the ‘64 games, I think it was. And their experiences were wonderful. So maybe it’s because they’re military, I’m not sure, but they only had wonderful things to say about how they were treated there.

And then one of the final highlights I wanted to share. This was an unexpected discovery. During one of the summer tours of the Royal Giants going from LA to Hawaii to compete against both Nisei or Nikkei teams, Japanese American, and teams from Japan, I discovered a guy named Eusebio Gonzales, and he had played for the Boston Red Sox in 1918. And here he is now, he’s a Cuban ballplayer, he’s playing with the Royal Giants; that’s him standing next to Andy Cooper. And it’s one of the few rare cases of a Major League ballplayer making the move back to or going to the Negro Leagues. Normally throughout history, it’s a Negro Leaguer going to the major leagues. So I just wanted to share this because I think there’s maybe a small handful of this occurring. So just an interesting story about Royal Giants. So with that, that’s kind of the few highlights I wanted to share, I have a few just in notes, not slides if you guys want to hear more, but we just open it up and start talking. If you guys have any questions about anything I can share.

Shane:

Thanks for that Bill, there’s lots of fascinating stuff. There’s so many rabbit holes and nuggets.

Bill:

I’m good to go as deep as you want. Oh, and also again, let’s not forget Ralph, I was going to mention Harry Kono. Oh, he was a good friend of Zenimura. He was part of the 1937 tour, for what was actually called the Kono Alameda All Stars, Zenimura was a coach with him. But Harry Kono signed, correct me if I’m wrong, Ralph, the first contract with Jimmy Bonner?

Ralph:

Can you hear me? Old technology.

Bill:

Are you on AOL?

Ralph:

No, no; just old school equipment here. I don’t know if anyone else signed with Harry, Jimmy might have been the only, as far as I know.

Bill:

In one chapter, on page 211 of the book if you should buy the book, a great essay from Ralph on Jimmy Bonner’s career in Japan, he was from Louisiana, I believe originally.

Shane:

Leon points out that one player to play all nine positions in a day was Will Ferrell in Spring Training.

Bill:

Yes! I was there for the first two positions he played.

Shane:

The documentary HBO made was very good. Andrew Romine also did it with the Tigers. So I think you mentioned this with the kind of inner face and outer face. You mentioned how up until Kaz published his book, all the documentation of the US tours was done from more of a Western perspective in the English language. So what was it that made his perspective unique, and why was it important to have this different perspective?

Bill:

Well first of all, just like what I shared with Honne and Tatemae, I think hearing those experiences from the Japanese ballplayers themselves, I think that was missing the entire time. But it’s also fascinating, some of the hidden gems from the Black ballplayers themselves that were in the Japanese press. There’s a wonderful long letter that Lon Goodwin wrote to one of the Japanese newspapers, we didn’t find that until Kaz shared it with us well. So he’s actually sharing more of the Negro League perspective. There was some of that in the Black newspapers, the Defender, the Courier, but not to the degree that they were available in the Japanese press. It’s important that all voices are heard when it comes to diversity, equity and inclusion. It’s basically the perfect example of history in general, that it’s always been kind of the white male perspective, and I can say that as a white male. It’s important to hear other voices, and I know I am a white male working on this type of project. Rob has another white male comment.

Rob:

So to me, it’s kind of obvious. I think what you’re really looking at is the perspective from the players against the perspectives of the management and the fans. Now what Kaz did- and I’m just like realizing this moment, I’m very critical of Kaz- I think what Kaz did was uncover what the players were feeling, and they weren’t given a voice in the Japanese literature. When you go back and read the stuff that I’ve read for the beginning of the Pro League, it’s written by the owners, it’s written by the newspapers that are behind the new league. So it basically does not take the players’ perspective. You’re right, it doesn’t say, “Okay, how did the players who are getting their butts kicked actually feel,” and I think that’s a really wonderful insight.

Bill:

One thing I did want to add is that, it also pointed out where there might have been misunderstandings too. And Rob, through a conversation that we had, Kaz goes on quite a bit about Lou Gehrig. Very critical of Lou Gehrig and his interactions with the Japanese, for a couple reasons. One, Lou showed up with this expectation of this Samurai spirit being present in all these ballplayers, and they were being ridiculed, in the way that they were playing in a way that you know, that nervous kind of laugh when you’re embarrassed, they were laughing as they’re running the bases, and that really pissed Lou Gehrig off. So he made a comment about that in the final dinner, and all the Japanese, as Kaz was saying, they were shocked that he would be critical, and make that comment in public. So that was ding number one against Lou Gehrig. Number two is, he gets hit by a pitch in his hand in Japan, and he sits the entire tour out after that. And automatically they think, “This guy is trying to protect himself so that he can go save that record over in the US.” Which, from their perspective, that’s what it looked like. But Rob, you pointed out to me that Lou Gehrig was actually pretty hurt. They took x-rays of his hand, he almost didn’t go through spring training the following year, he just barely recovered. So I don’t think they really fully understood the extent of how injured he was, his record actually probably could have ended, and he couldn’t have played, he wasn’t physically able to compete. So you can see where misunderstandings may have taken place. And there’s a really interesting misunderstanding with regards to Zenimura and the Royal Giants. So Lon Goodwin tells Zeni that he’s taken over the LA White Sox, so he’s thinking that’s the team they’re going to play over there, but it’s the Royal Giants. So again, it’s these better players that really enhanced the team. But Zeni doesn’t know that. So they’re being interviewed by Japanese press. And then he says, “Oh, yeah, we beat them three times over in the US, we feel very confident.” And that really upsets Biz Mackey, and some of the players like, “We’ve never played them,” he’s basically lying. So I think, and I mentioned this in the essay that I wrote about the birth of the tour, that Biz Mackey played angry that day. So that’s when he hit that first home run, and I think he was like, a double, or maybe a single shy of the cycle. He just tore it up. And so there was that misunderstanding from that perspective, as well. And that was verified by Kyoko Yoshida, who got a copy in the Japanese press, of all the players that Lon Goodwin said who were going to go, and it was basically all of the Negro League stars, as I mentioned earlier, Turkey Stearnes, Bullet Joe Rogan, and all the great players who were on that Royal Giants, California Winter League team. So anyway, a lot of misunderstandings and things getting lost in translation, if you will, over in Japan.

Shane:

You mentioned the importance of getting different perspectives. Can you talk a little bit about Phil Dixon and the work he does, and the other historians that are working to document the Negro Leagues?

Bill:

I’ll share what I know. I don’t know Phil, personally, but I know that he’s a very important figure when it comes to this historical research. I think he may have been one of the original founders of the Negro League Baseball Museum. I don’t know what happened with those relationships, but he’s done a lot of archiving as well. He owns an extensive photography collection, which is why Kaz hunted him down. He is a very important voice when it comes to Negro League history. And actually, this was one of the interesting insights for me as well, and this is kind of a little humor side, at least it was to me, you guys familiar with the movie “Christmas Story” where the kid gets the decoder ring, and he works really hard, he decodes it and it says “drink more Ovaltine.” and he’s very disappointed after all that hard work. So I’m working on this translation project with this whole team, and I get to the very end, and Phil Dixon tells Kaz “we need fewer white guys working on the Negro League History Project.” A “drink more Ovaltine” moment. So one, I thought it was kind of funny, so I also put it in its perspective from history as well, he was talking about 1985, and I think it was a different dynamic. I’ve got my own personal reasons, and you’ve met my family virtually, at least what I shared. I think intent is very important as well. I think in 1985, there may have been a lot of people trying to take advantage financially, of some of the history in the archives, and the memorabilia and things like that. I think he may have been referring to that. But I do think it’s important, and from the other side is that, as an African American male, he’s going to have shared experiences that he can relate to and articulate, that I personally can’t. But that’s the same thing with me and my son, when he goes out in the world, he has a different experience than I do. The work that I did on Zenimura, this is the quote I go back to, it’s actually Alice Walker, African American author. She may write about the African American experience, but she’s really talking about the shared human experience as well. And so that’s what I feel like I’m relating to when I find these stories, and I think it’s important to preserve them, make them more accurate for history, and to kind of dedicate my time to them. And drink more Ovaltine!

Shane:

Well said, and you do a great job. And hopefully, it can encourage others to do more, someone’s gotta do it.

Mark:

I do know John Holway, can I just say that sometimes you have to take his research with a grain of salt. I’ve been in SABR a long, long time. There’s been some questions about John. I love John, don’t get me wrong. I’m just saying that his research, he might have embellished some things over the years.

Bill:

Well, I don’t know John myself, I only know of his work. But I’ll defend him in that they came around at a certain time where they were fortunate enough to interview the players themselves, and players’ memories really weren’t that good. So I think in some cases, there was a kernel of truth, and they kind of captured that kernel. But now that our generation, we have access to better Digital Archives, newspapers being more accessible. We’re the validators, we’re coming up behind him and saying, “Okay, there was a kernel of truth, but really what actually happened there?” So that’s kind of his clues, and then we go forward and verify it or debunk it. Rob, is that some criticism you have of Kaz and his work that he did?

Rob:

Bill, that’s exactly right, since I’m constantly going back through his work, and I find major mistakes. But here I am, 20, 30 years later with Baseball Reference and newspapers.com. I mean, I have every single genealogical database available at my fingertips. I can check his facts in seconds. So yeah, all sorts of problems. Right? But he didn’t have that, he would have had to go to that small town. So yeah, we really are midgets on the shoulders of giants in a way, and we have such benefits. It’s just important in research, I know we agree on this, that we’re open and that the older people are open to our well meaning criticisms too. We find something and it’s like, “Hey, you know what, sorry, guy but you were wrong.” You know, we have to say “All right, you know, it’s not personal. It’s facts.” And as you point out when I’m wrong, “Yeah, it’s not personal.”

Bill:

Sure. And by the way, when we translated Kaz’s original ‘85 book, we left the mistakes. And then we put a little footnote next to it, saying, “Hey, he said this, however, this is what we discovered.” So I felt it was important to try to stay as authentic as possible. So I actually got the impression that he wanted me to maybe take it in a different direction, and maybe clean it up even more and make it more polished. But I don’t think that was my role, because I think there would have been a lot of questions about the integrity of what he said, versus how I maybe pushed it too far. So I think I’m phase two of maybe a future phase three, for somebody else to take it and do something with it, something bigger. And on that note, I’m excited to share that a few different companies in the film space have expressed an interest in it. So documentaries, maybe a movie, maybe a miniseries, like Netflix or something. But I think there could be a lot of interest right now, especially with the world we’re in and some of the dynamics we’re having to deal with. We talked about these ball players being treated like second class citizens in the 1920s and 30s, and man, here we are again in 2020.

Shane:

It’d be such a great historical timepiece. All of us baseball dorks on the call here, we’d love to see them in the old uniforms and all that, but then to see it try to recreate Japan and the time, that’d be such a cool, ambitious production effort.

Bill:

Did we all see “The Catcher Was a Spy?” Paul Rudd? So there was a Japanese official who he developed a relationship with at some point in the movie. That individual is in my presentation, he was the one Lou Gehrig had his arm around. So that was Takizo Matsumoto. He’s a Hall of Famer in Japan now, he’s been recognized for all the work he did from the Japanese side, for the goodwill tour, bridge building, if you will. So I just wanted to point that out, that he was a pretty important figure. He actually graduated from Fresno High School in 1919, then moved over to Japan, and played an important role with a lot of the Olympic Games. He was supposed to be the head of the Olympic Games in 1940, but it was cancelled. But he had a pretty important role behind the scenes with a lot of the tours.

Shane:

Interesting. Yeah, they did a good job with that, really, I love that book, too. Yeah. Speaking of Japanese Hall of Famers and photos, so I forget his name, but the guy on the cover of your book, is the one that became the manager and then brought the two black players to play for the [Hankyu] Braves?

Bill:

So Shinji Hamazaki- apparently there is a biography on him over in Japan, I’d really prefer not to go through the translation process again, but one I would like to read. My understanding is that he specifically said he wanted black ballplayers on his team. He toured the US in 1928, after this ‘27 tour, and they played against historically black colleges and universities, so he had a great experience in the US interacting with black players as well. So some of the first black ballplayers that were on his team, again, I think the quote, and I’m paraphrasing, that he said he was going to quit as a manager if they made him get rid of the African American players on his team. So he felt a strong commitment having them on his belt.

Shane:

And when he brought them over, was that when they first started to formally allow import players, and he went straight to get Negro League players?

Bill:

My understanding is that it was some sort of relationship with maybe Bill Veeck and Abe Saperstein. So yeah, some of those players might have been on loan. But yeah, those were the first, kind of more official, after Jimmy Bonner.

Eric:

I’ll butcher the name of the league. But in the book, he talks about a league I guess was based in Berkeley, or around Berkeley, that was kind of the first integrated league really. Can you talk about how that came about, and that was groundbreaking for its time?

Bill:

That’s interesting. So that’s actually Ralph’s area of expertise. It’s called the Berkeley Colored League, and it was a multicultural league in Northern California, Berkeley, Oakland, that area. So it’s a very important league from a multicultural international perspective in Northern California, but it’s really not the only one or the first one. All up and down the coast. We actually identified a Negro League team in… definitely LA. You’ve got the LA Trilbys, I believe they were called in like the 1890s or so. Then, in San Diego, there’s some teams in the early 1900s and then that was kind of the foundation for the California Winter League and having those black teams there, the LA Giants. Bill Pettus was a pretty famous Negro League ballplayer, played there in California, competed against one of the teams that Rob wrote about in early 1909, a Japanese American team. So yeah, a lot of interaction between Japanese ballplayers and Negro League ballplayers on the west coast. So it makes sense that Harry Kono signed Jimmy Bonner in Northern California.

Shane:

I was glad you brought that up. I really like that section too, and I actually took a picture of that section and sent it to a couple different people I know who live in the East Bay in Berkeley and Oakland, that would be really into it and they both got a kick out of it. I guess you’re saying it was not necessarily rare, but it does seem like a Berkeley thing.

Bill:

Can I just mention a few other names of players I took notes of that I thought the group might find of interest? A young pitcher in Hawaii named Bozo Wakabayashi. He pitched for the Honolulu Asahi. There’s a famous picture, it’s actually in the book, of the Philadelphia Royal Giants holding a trophy cup that was against the Honolulu Asahi, and Bozo- I think his first name is Tadashi Wakabayashi- he was just a relief pitcher in that game, but he’s in the Hall of Fame now in Japan, played for the Hanshin Tigers. This is the bit of trivia that I like about him, is that he wore the number 18. And my understanding is that the ace of a pitcher now on the Japanese team, will wear number 18, in honor of Bozo. So anybody know that story? Anybody want to fact check me on that?

Rob:

Yeah, it’s an honor of Sawamura I think.

Bill:

You sure?

Rob:

Sorta.

Shane:

Actually this came up recently, and Coop is on the call as they begin to write an article about and look into it, see if we can figure it out.

(Editor’s note: definitely will put more research into this, but it seems that during the Yomiuri Giants’ nine-year dynasty, management gave the number 18 to their ace pitchers. American pitchers like Daisuke Matsuzuka have said they watched the best pitchers wear the number when they were young, hence why they wear it in the States. For some like Matsuzuka, the number was even required in contract stipulations, and some of the best currently still wear the number, like Kenta Maeda of the Minnesota Twins.)

It seems like it’s definitely a thing that aces wear 18, and when Japanese players have come over to the US, they make a point of wearing it.

Bill:

Sawamura wore number 11, according to Trevor.

Shane:

But it seems to be in the English language, there’s not much definitive out there that explains what the actual origin was and how it became a league-wide thing, as opposed to just a team-specific thing. So if anyone has anything on that, let us know. We’d be curious, it’d be an interesting article.

Bill:

Let me check my notes here. Frank Duncan, played for the Kansas City Monarchs, he was part of the tour. He was a first baseman and a catcher. He was Jackie Robinson’s coach when Jackie played for the Monarchs in ‘45. And Rob, correct me if I’m wrong, but I think Jackie Robinson hit his last home run in Japan.

Rob:

Yes, he did, and played, of course, his last game. last run, last hit in Japan.

Bill:

Great. Although I did find Jackie Robinson throwing out the first pitch in the 1958 Negro League All-Star game, East-West classic. And the starting pitcher, after he threw out the first pitch, was Charley Pride, who was just recognized with the Country Music Lifetime Achievement Award. So how’s that? You can visit my blog, zenimura.com and learn about Charley Pride’s relationship with Jackie Robinson. I deviated a little bit from the Japanese baseball, but Charley Pride is an international country music sensation. So it seemed appropriate to include that. All right.

Shane:

Well, anyone else have questions out there before we wrap it up?

Bill:

I mentioned the film conversations, but those are just conversations. If anyone would like to engage in more conversations, we’d love to discuss it.

Rob:

Oh, here I am dominating the conversation, I’m sorry. So we’ve talked about this on the internet, our emails back and forth. But what are your thoughts, for public consumption, on the myths surrounding the Royal Giants, and all the false information? I was told by a very prominent member, you’ll know who I’m talking about without mentioning his name, that the Negro Giants professionalized Japanese baseball. I was told this or read this last week. And so do you want to talk about that at all?

Bill:

Sure. I kind of feel like I already addressed it with the one slide about the timing, and how people are maybe taking snippets of Kaz’s statements and taking them out of context, if you put it back into context, professional baseball was able to come about when it did, because of the Royal Giants, and their influence, in 1936. So again, to me, it’s more about the timing. He says eventually, he follows it up, that it would have come along. So to me, it’s pretty clear we’ve ironed that wrinkle. The next wrinkle is, did the Royal Giants visit the Emperor’s palace? Were they greeted by him? Did he give them a trophy, etc. So I think what happens in this situation is legend and lore, three different stories kind of being twisted up and becoming a rope, and we have to unravel it. So one, Rap Dixon was recognized for a great accomplishment over there at the time, Koshien had the furthest outfield, again, it was 420 feet. Nobody had ever hit the ball out of that ballpark, and he did not hit the ball out of the ballpark. He hit a line drive triple off the wall, and after that, they painted a white spot on the wall, and that was the recognition for a great hit at the time, the longest ball ever hit in Koshien. So yes, Rap Dixon was recognized for great athletic achievement. Did they visit the Emperor’s Palace? Lon Goodwin says that they did go, in his 1927 letter that he wrote, and actually a biography that one of his ballplayers, Alfred Bland, wrote about him, it’s in the appendices. He says that they were greeted and welcomed at the Emperor’s Palace. Now, was it the Emperor that welcomed them? We don’t know, we don’t have a photograph. But there was some event or occasion that took place at the Emperor’s Palace. And then the third thing is the famous photograph of the trophy with the Honolulu Asahi. I think when you take those three things, Rap Dixon, the Emperor and the trophy, it somehow has become Rap Dixon received the trophy from the Emperor at the palace. So that’s all I can validate with what I know. And again, that’s what we kind of do is we find the kernels and try to find the truth. So having said that, I think the person who we’re speaking of, shares this visual of Rap Dixon with a trophy in a coloring book for small children, or elementary school children, so that they can learn the story about Black ballplayers in Japan. To me, I think that’s kind of like George Washington chopping down a cherry tree, that we need to pick our battles, and I think that’s appropriate for that audience.

Shane:

Thank you. I mean, I learned so much. Rob, thanks for all your input to and glad to be able to parlay your one Zoom call to the next. So thanks for joining us. So yeah, Bill, thanks so much for doing that, and for all your effort, not only on this call, but just in your research in general and sharing it with the baseball world. We really appreciate it.

Bill:

My pleasure. Thank you guys for your time. I really appreciate it, thanks for your patience and Ralph, thanks for contributing to the book.

Shane:

Yes, Ralph. Thanks. Ditto to you on what I said to Bill- he’s saying thanks in the chat. At least he figured that part out. So everyone, yeah, you’re welcome to sign off. Good night to everyone. Thanks for joining us. And thanks again. Bill. That was really fun.