There’s no denying that Japan has a role in present-day Major League Baseball (MLB). With current names like Darvish, Tanaka and Maeda dealing on the mound and Ohtani wreaking havoc at the plate and on the basepaths, players from Japan show what talent can be found outside the United States, contributing to an international atmosphere in America’s Pastime. 25 years ago, however, this wouldn’t have been possible.

Before 1995, the United States-Japanese Player Contract Agreement, also known as the Working Agreement, outlawed leaving Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB) until a player had tenured ten years of service in the league. Many players would burn out before they reached this amount of time, as the dedication and diligence required to play in the league would strain their muscles and beat them down. What’s more, team owners held a stranglehold on the market for the players, and would negotiate contract offers with their players like hostage situations; one-on-one, no outside influence.

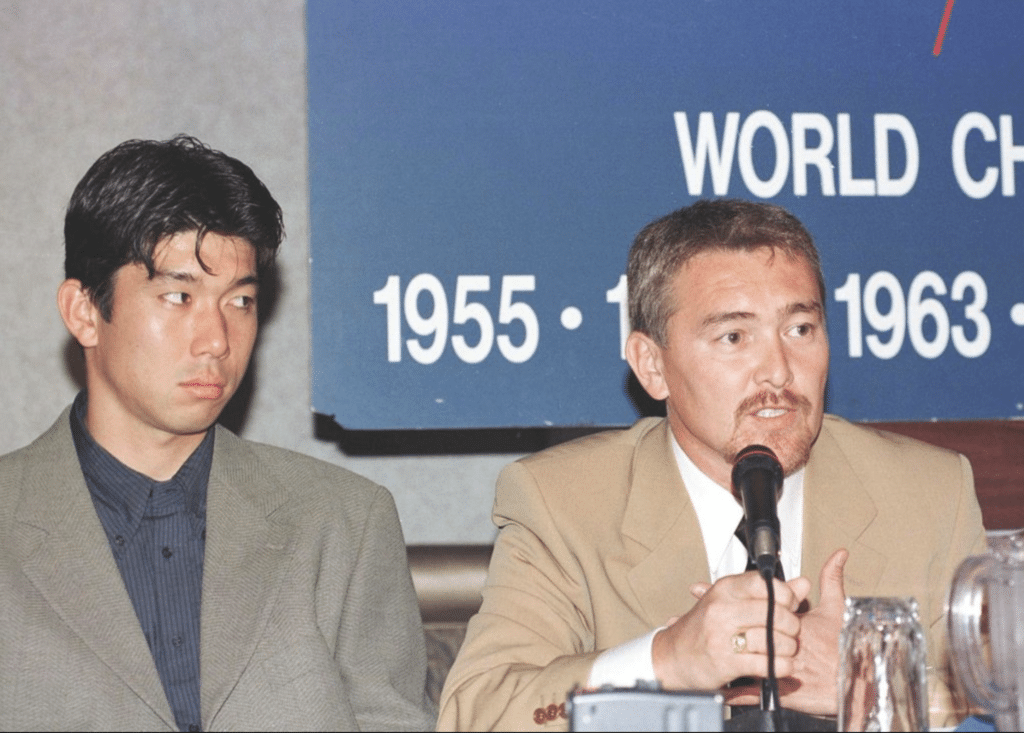

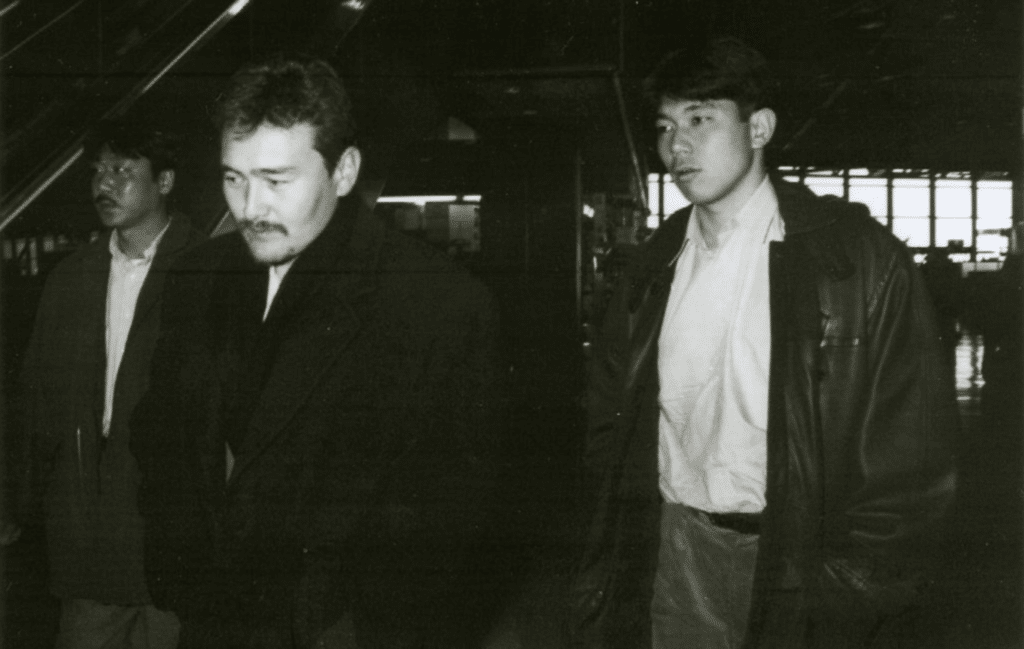

Which makes a story like Don Nomura’s, the first professional sports agent to negotiate player contracts in Japan, so interesting. Called the “Darth Vader of Japanese baseball” by writer Robert Whiting, Nomura not only secured Hideo Nomo’s right to play for the Los Angeles Dodgers, but also dozens of Japanese players who followed his footsteps across the Pacific. In doing so, he not only changed the environment of baseball in the world, but also players’ rights to choose and advocate for themselves.

To leave it at just that, however, isn’t a good story; that’s what the rest of this article is for. These are Nomura’s greatest hits, including how he grew up as an outsider in Japan, how he became invested in the business of sports, how he secured the contracts in three lengthy struggles with NPB, and finally, how MLB-NPB relations changed because of it.

Buckle up. It’s going to be a fun ride.

Part 1: Early Life

Nomura was born as Donald Engel on May 17, 1957 to parents Alvin Engel, an American, and Yoshie Ito, Japanese. His life was filled with hardship at an early age. His mother left when he was six, leaving Alvin to raise him and his brother alone, and his mixed blood led to him being derogatorily labeled “konketsu,” a term for mixed children. With fiery red hair but an ability to speak Japanese rather well, Nomura later said that he didn’t quite know what his identity was.

“I think living in a country where I thought was home and growing up in a one-race nation was pretty tough,” Nomura said during the August 13 episode of JapanBall’s “Chatter Up!” “Right after the war, realizing you kind of don’t understand the racial bias stuff, but you’re thrown in there and growing in there. But luckily, I went to an international school where a lot of kids like myself were there, so that kind of helped me, starting to understand and all that.”

Although he began to understand who he was, it didn’t eliminate any passion he felt. He was kicked out of his first high school in Tokyo for fighting when he was sixteen, and gained a reputation in his new one for his rebellious nature. Although he had a knack for trouble, he also became a standout athlete in his school years, playing baseball with Chofu High School in the Tokyo suburbs. By graduation, he garnered enough attention to play at California Polytechnic University in San Luis Obispo.

When he turned 21, his dual citizenship was rescinded due to Japanese laws and the government told him to choose a country to remain with. He chose to be Japanese, citing that NPB only allowed two foreign players at the time, and began visiting with his mother again. In an interesting twist of fate, his mother had married another baseball player, the legendary Katsuya Nomura. Katsuya, who sits behind only Sadaharu Oh for career home runs with 657, adopted Don himself and gave him his name.

“He always had that complexity in his heart that drove him to do well, not only as a player, also as a manager, and also as I think a human being,” Nomura said. “He was amazing. Great stepfather and great person. I really miss him.”

After graduating from college, Nomura tried to join the Swallows, but toiled in the minor leagues for a while. He continued to struggle with being an outsider, as he dealt with racist bus drivers calling him a “gaijin,” and punishments for trying to play; he once asked his manager to let him play in a game, and was benched for two weeks for doing so.

“Getting into Japanese professional baseball was just another level of toughness,” Nomura said. “It was a totally different environment for me, it wasn’t very easy. This is not something I dreamed of and hoped to make a living in. After maybe two years I thought this is not my place.”

As a result, Nomura once again left for California in 1981. He met financial troubles quickly, as he worked a series of odd jobs in restaurants and flophouses, but continued to save money and turn it into something profitable. After a lucky night in Vegas turned his $1,000 savings into $41,000, he invested in real estate, and turned enough profit to get his own business underway. In 1989, he met with a group of investors and purchased the Salinas Spurs, a Class A baseball team in the California League that Nomura envisioned serving as a sort of US-based minor league team for the Hawks and Swallows. Nomura was the second Japanese citizen to ever own a baseball team in North America.

Although not the greatest team to start with, the Spurs allowed Nomura to gain one necessary tool: professional baseball management experience. It was here that he first dealt with players, and also nurtured the talent of a 17-year-old clubhouse attendant, a scrappy right-hander named Mac Suzuki. Kicked out of high school for fighting, Nomura took Suzuki under his wing and became his agent, negotiating a deal for him with a million dollar bonus with the Seattle Mariners in 1993.

With his first client, Nomura sold his Salinas shares and founded his own agency: KDN Sports (now Amuse Sports). After years of struggles, hard work and a little bit of luck, he had become a player of his own accord.

And with this in stride, he once again turned his sights towards Japan.

Part 2: Nomo

After his experience with Japanese baseball, Nomura recognized that there was likely unrest in the NPB. With the players being worked down to the bone and the ownership peering over their shoulders for more innings and more hits, he felt that there would be some players who would want to fight the system. He began his search for a renegade; someone who could test the system and try to fight for his own right to play.

He found it in a right-handed tornado in Osaka named Hideo Nomo.

A little player profile for those unfamiliar: Nomo’s best tools were his fastball and forkball. His “tornado windup,” as unorthodox as it was, helped the pitcher flame fastballs past confused hitters, and his forkball baffled them to boot. After playing in the Industrial Leagues and starring at the 1988 Olympics, Nomo was drafted and signed for a record 100 million yen ($1 million USD) by the Kintetsu Buffaloes in 1989. He quickly shined for the team, leading the league in wins, ERA and strikeouts (18, 2.91 and 287, respectively) and earned both Rookie of the Year and the Sawamura Award for best pitcher. He’d continue to lead the Pacific League in strikeouts until he left in 1994.

After this period of success, however, Nomo’s patience was wearing thin. His manager, the Hall-of-Fame pitcher Keishi Suzuki, would overwork him with lengthy starts of over 140 pitches, even on bad days. His shoulder began to quit on him, but he still pitched through it, showing no emotion to his manager; it would require surgery following the season’s end. What’s more, Nomo had always shown a desire to be in MLB; he often read Nolan Ryan’s philosophy of pitching, and constantly spoke with “gaijin” about life in America.

“I think his dream was to play in Major League Baseball, he just didn’t know how to get there,” Nomura said. “The only [chance] he had was to join the NPB then. But his dream was always to somehow play in the United States, and the dream even got bigger when he played against the MLB All-Star teams. So his dream was stronger going to the States, rather than [his] disliking the establishment in Japan.”

Nomo was worried; if he continued to be used the way he was, his shoulder would be completely ruined by the time the required 10 years passed, eliminating any value he’d have in the MLB. His desire was not a secret, and it began to spread as a rumor through the league.

As a result, when Nomura came to Japan looking for an ambitious star, the grapevine led him to Nomo. The two met in a coffee shop discreetly, and began to discuss the idea. Nomo asked Nomura questions about it, whether his arm would get proper treatment and his own practice sessions, and Nomura answered them all as plainly as he could. At the end of the day, Nomo had made up his mind; he was coming to America.

“Obviously he didn’t truly understand what the reservation was, the free agencies, the injuries and how he was used and all that, and that we have to discuss [to] fully understand that the system was totally different from [the] US and Japan,” Nomura said of the discussion.

The problem was they had no idea how to get him there, as the MLB-NPB Working Agreement was still in place. Nomura, charged with the possibility of a Japanese MLB player, enlisted the help of lawyer Jean Afterman to pour over the language of the Working Agreement for an escape clause. Afterman, now the Assistant General Manager of the New York Yankees, said the two would go at it every day after work.

After a few days, they found the possibility, although they didn’t quite believe it at first. The Working Agreement specifically mentioned that it only applied to “active” players; meaning that if a player were to “retire,” they’d be free to leave and test the waters elsewhere. In a query between the Japanese and American commissioners arranged by Nomura, they received their smoking gun: the Japanese league confirmed it as true.

Of course, Nomo would first have to be released from his contract with the Buffaloes and make them force him into “retirement.” Nomura came up with a plan: anger the Kintetsu management enough to believe that kicking him out was the only option. Nomo and Nomura headed to the team offices in Osaka, and, by sitting at the meeting, Nomura became the first sports agent to negotiate for a client in Japanese baseball.

Kintetsu celebrated this achievement by trying to kick him out of the meeting. Nomo went with him. The two were a team, and they were determined to reach their goal.

“I’m kind of used to being kicked out. I was kicked out of school, out of office,” Nomura said. “Hideo knew that I was not allowed but he said, ‘let’s go.’ We went in together. They kicked me out. Hideo says ‘I’m leaving with you’ to the General Manager then, so he was very cooperative. That’s the kind of client you want to have, that can support you and you can support him together. And that makes good synergy as a team.”

They did this first by demanding a ridiculous contract of six years, $30 million, when Nomo wasn’t even a free agent; Kintetsu responded by kicking them out of the meeting. In a second meeting, Kintetsu pleaded with Nomura that they couldn’t afford the deal, as the team and company were losing too much money. Nomura’s response? If they were losing money, maybe they should sell the team to someone who wanted to win. They then got kicked out again. They pleaded with Nomo until the team president got so angry, he demanded that if it didn’t cease, he would force Nomo to sign retirement papers then and there.

Nomo complied. He left the team, and in February 1995, signed with the Los Angeles Dodgers to become the second-ever Japanese born player to play in the MLB.

For this, Nomo and Nomura became universally despised in Japan. His refusal to comply for the good of the team led fans to call him selfish and a traitor, and his own father told him to calm down and just stay with the team. Nomura got death threats and was told he was destroying professional baseball in Japan. But the two didn’t buckle. They left for L.A with their heads held high and their mission accomplished.

“I think this whole thing I think really supported him because of this whole negativity that was against him, and I think it really helped him make sure that he had to do well just to overcome, and that became an energizer for him,” Nomura said.

Three months later, Nomo became an international phenomenon. He had an unbelievable rookie campaign, starting the All-Star game and winning the Rookie of the Year award, and wowing American fans with his revolutionary delivery. Japan noticed this success, and began to tune into every game he started with the Dodgers. The fans who once spat at his name and called him a traitor were now watching with a sense of national pride, as Nomo showed the MLB what Japan had to offer. Nomo-mania had officially begun.

“Once he started doing well, it just turned everything around because they needed to focus on him, get the ratings,” Nomura said. “It was a surprise, but as I look back and kind of look [at] what happened to how the market evolved, I think it was just a natural way of media shifting from negative to positive.”

Nomura had done it. He had won his first major battle with Japanese baseball. But as Nomo tore through the MLB, more struggles laid ahead for Nomura.

Part 3: Irabu

Although the fans were going nuts for Nomo, the NPB was not exactly pleased with the development. They’d been duped. Desperate to not let it happen again, they stripped the working agreement of the “retirement” clause, not even bothering to let the MLB know they had.

Meanwhile, a fiery hot-headed right-hander for the Chiba Lotte Marines named Hideki Irabu was feeling ticked. Irabu, with a fastball reaching 99 mph and a disdain for Japan’s long practices, wanted to test the waters in MLB and play with some of the best players in the world; even then-manager Bobby Valentine told him he had a shot. He chatted with team officials about a trade that would send him to the States, with a hope that he could be sent to the Big Apple and play with the all-mighty Yankees. Irabu, hopeful that the team would honor his wishes, hired Nomura to ensure his dreams.

Although Lotte was originally content with the idea, their owner, Aiko Shigemitsu, didn’t feel Irabu was fully cooperative, and threatened that if Irabu wasn’t respectful enough, he would eliminate his baseball prospects as a whole. In response, Nomura threatened to take the team to a court in the States if they didn’t comply. Finally, a bizarre agreement was reached: Irabu would write a letter declaring his full allegiance to the team, and Lotte would do their best to send him to New York.

To their credit, they did talk with New York about the possibility of getting Cecil Fielder in exchange, but at a discounted salary. The Yankees didn’t budge, however, and Lotte instead sent him to San Diego. They called him and said that there was nothing else they could do, and that he was San Diego’s problem.

Nomura, refusing to back down, rejected San Diego’s contract offer. San Diego responded that if he didn’t play, the team would be forced to hold him out of the league for a year. Nomura, furious at the idea, brought the team in front of the MLB Players Association (MLBPA) and argued not only did the working agreement forbid such a trade between the two teams, but the fact that Irabu was treated like such a piece of meat was absurd, and that he had the right to choose where to sign as a result; in doing so, Nomura called the practice “a slave trade.”

What resulted was a million dollar game of chicken. Lotte presented the letter that swore Irabu’s allegiance was with the team, regardless of what happened. The MLBPA ruled that while Irabu had rights, the trade wasn’t prohibited per se. Nomura and Afterman boldly declared that the “slave trade” was still in effect, and that Irabu wouldn’t play a single game in San Diego. Lotte fired back that Irabu wasn’t welcome back in Japan either.

With all the cards on the table, Nomura played his final trick; Irabu was a prisoner in circumstances he could not control; he was trapped in an internment camp because of his Japanese heritage, and for that reason, the whole environment was unfair to him.

The MLBPA took notice, claiming that Irabu was treated unfairly. The trade was frozen, and new legislation was drawn up that prohibited any similar trades unless the players involved agreed. San Diego, sick of the whole affair, sent Irabu to the Yankees, and the affair was over.

Nomura had won again, securing his client a role in MLB and getting the working agreement open as well. With more confidence and gusto than ever, he turned back to Japan for one more challenge: a young slugger named Alfonso Soriano.

Part 4: Soriano

Soriano had been recruited to NPB when he was just 17, signing with the Hiroshima Carp and being assigned to the Carp’s academy in Soriano’s home country, the Dominican Republic. Playing for the Carp, he developed into a wonderful, toolsy prospect at second base, with enough speed and home run prowess to garner attention. The Carp, however, refused to pay him above the league minimum at just $45,000. With a disdain for his pay (and dislike for the practice regiment of Japanese ball), Soriano hired Nomura to try to get him a more fair shake.

Nomura and the Carp already had a history. Before Soriano, Nomura had represented a player named Robinson Checo, through whom he found out the Carp were paying less than half of the minimum salary for a Japanese player. Taking a stand for the Dominican Republic, Nomura boldly claimed that nonwhite foreign players were often signed into lengthy contracts for less pay, making it that a Dominican player would spend their entire career just trying to fulfill their contract.

With this in mind, Nomura and the Carp were already not on great terms. When the parties entered arbitration, it led to a meeting with the NPB commissioner and league presidents that Nomura wasn’t invited to. When the result wasn’t as great as they would have liked, Nomura recommended Soriano try retiring like Nomo.

The Carp threw a fit. They argued that Soriano was still their player and their property, and wrote to all MLB offices that they could not touch him. The MLB took note, and held another executive meeting to review the case. When they met with NPB lawyers to discuss, they noticed changes had been made to the working agreement.

Remember how irate NPB officials were when Nomo retired to use the loophole? How they were so mad that they changed the rule without telling the MLB? Well now that they tried to show that the loophole wasn’t valid anymore, the MLB noticed they had made this change without any consideration Stateside.

The MLB got mad. Extremely mad. They argued that the NPB’s alterations led to an environment of distrust, and to simply continue following this agreement would be unfair to both them and the players involved. As a result, they scrapped the agreement and allowed Soriano to become a free agent; he would sign with the Yankees for five years, $3.1 million, and later the Cubs for one of the richest contracts in MLB history: Eight years, $136 million.

Pretty decent upgrade from $45,000.

Part 5: The Posting System

A few weeks later, MLB released their new plan for Japanese players coming to the States: the posting system. Under the system, Japanese teams would “post” players who they’d be willing to send to the States (provided the player agreed/wanted to go), and the MLB team that bid the highest for the player would get his rights, with the money going to the NPB club. The MLB team would then have 30 days to sign the player.

With this signed and settled, the bridge between the two leagues had finally been built. No longer would a player have to dance around loopholes and scour legal documents for escape clauses; now they had some rights, a choice to go or to stay, and more opportunities than ever before.

One could argue that it was Nomo’s bold choice to go in the first place. One may say it was Irabu’s stubbornness that led to the players’ rights. Others may say Soriano’s case led to the changes. Yet, the one common thread for all three? Their agent, a fiery, red-haired outsider with a cool attitude and refusal to back down.

Because of Nomura, Major League Baseball hasn’t been the same for the past 20 years. It’s been filled with Japanese superstars like Yu Darvish and Kenta Maeda, both of whom Nomura represented in their transitions to MLB. He continues to help build the community and world of international baseball, even with all he’s done.

It was his fighting spirit and rebellious attitude that got him into trouble in high school. Many years later, he’s still causing trouble… just with human rights instead of fists.