If you ask any casual fan of Major League Baseball (MLB) who the greatest Japanese player is, many would immediately respond with a single word: Ichiro. The Toyoyama native spent over 18 years in MLB, racking up impressive totals with 3,089 hits, a stellar .311 average, and even setting the MLB single-season hits record with 262; he was widely recognized for these achievements, winning American League MVP in 2001, as well as 10 All-Star nods. These impressive numbers also came after he spent eight seasons in Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB) in Japan, where he led the Orix Blue Wave to two Pacific League pennants and a Japan Series victory in 1996, while also garnering three league MVP awards and seven times being named an All-Star.

And yet, Ichiro’s success would have never happened if not for the word of an Orix scout, who convinced his executives to draft Ichiro in the fourth round of the 1991 draft despite concerns over both his small stature and his awkward, unusual batting stance. The scout told his higher-ups that he would work with the kid to ready him for the advanced level of NPB.

Several books, articles and even television spots have been made about Ichiro’s life and success, but the scout that found and developed him into a superstar usually only gets two facts mentioned about him:

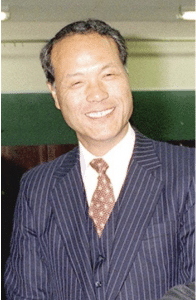

- His name was Katsutoshi Miwata.

- Seven years after finding Ichiro, he killed himself after failing to sign Orix’s top draft pick.

This is the story of Miwata: who he was before Ichiro, how he got involved in scouting for Orix, the success of the team following his contributions, and his death shortly after. And although this may not be a complete history of his life and achievements, it will hopefully serve as a gateway to the culture of Japanese baseball… and the stress that underlies it.

Part 1

Enter: Katsutoshi Miwata

Miwata was born on July 11, 1945 in the Aichi Prefecture, and was raised in the Chukyo Metropolitan area. Not much is found about his early life, apart from the success he saw as a pitcher with both Chukyo Community High School, under famous player and now coach, Toshihiko Hayashi. In his junior year in 1962, he saw time in the prestigious spring and summer Koshien tournaments as a relief pitcher, including an outing in his team’s victory over Kagoshima Commercial High School, but saw his team lose to the eventual champion, Sakushin Gakuin.

In his senior year in 1963, Miwata saw extended action as an “ace.” In the Spring Regional Tournament, he led his team to the championship and a spot at in the Koshien tournament with a victory in the final over Meisho Daisuke. He also saw time in Koshien, beating Tsukimi High School. Chukyo would make it to the third round of Koshien before losing 3-2 to Yokohama.

Following his high school success, he attended Waseda University in the Department of Commerce, and played with their baseball team in the Tokyo Big6 Baseball League. Established in 1925, the Big6 is perhaps the most historic league in Japan and serves as one of the highest leagues of Japanese baseball outside of NPB.

Miwata helped Waseda make up one of the most successful staffs in Big6 history, along with Soruka Yagisawa, who threw one of the sixteen perfect games in NPB history, and Naoki Takahashi, who spent eighteen years in NPB. The trio led Waseda to three titles, and in 1965, both Miwata and Yagisawa were selected to play for Japan in the sixth Asian Baseball Championship in Manila; the team would also win the title. In addition to team accolades, Miwata had one of his most successful seasons in 1966, posting a 23-9 record in 45 outings, and was also named to the fall season’s “Best Nine.”

After graduating from Waseda, Miwata was selected first overall in the draft by the Kintetsu Buffaloes, but turned down their contract offer and instead joined the Japanese Industrial League, pitching as an ace in for Daishowa Paper. Miwata played and worked with Daishowa Paper for three years, until being drafted again – this time by the Hankyu Braves – in 1969.

Although he continued to show great talent, winning his first game in 1970 and posting the most wins in the minor Western League in 1972, Miwata was never able to hold a permanent spot on the Braves. After three years of bouncing between the minors and the Braves, Miwata retired and took a scouting position with the club.

This is where the fun begins.

Part 2:

While he had a fantastic arm, what Miwata was really known for was his fantastic personality. Several teams across the country knew him for his kind actions, and even the Hall of Fame manager of the Braves, Toshiharu Ueda, famously called him “a block of sincerity.” Due to this personality, he often saw beyond simple measurements of size and stature.

Enter: Ichiro.

It’s hard to believe nobody paid him much attention in high school, even back then: Ichiro posted an unbelievable average of .505 and hit 19 home runs, all while helping his team as an ace pitcher. Teams, however, didn’t see him as a wunderkind, but a short, scrawny kid: at the time of the draft, he stood at only 5’9’’ and only weighed 120 pounds. As author Robert Whiting wrote in his book, The Meaning of Ichiro, “scouts were a little dubious of his pre-shrunk frame.” Every scout, that is, except Miwata.

Miwata discovered Ichiro and immediately urged the former Braves, now known as the Blue Wave, to draft him, while also taking the time to talk with Ichiro about his regimen and training to succeed in the league. While Ichiro had already put heavy work into his arms and coordination for hitting, Miwata recommended he worked on core strength. The scout introduced him to a regular routine of sit-ups and calisthenics, one that Ichiro practiced his entire Major League career.

Beyond training, however, Miwata became what Ichiro described as “a second father” to him, with others reporting that it was Miwata’s persuasion and kindness that convinced him to sign with Orix, a team he knew almost nothing about. Miwata also convinced the higher-ups to draft him despite his short stature, with a belief that he could turn into something fantastic.

And it did. After two years jumping between the team and the farm system, (and also hitting his first home run off the famous Hideo Nomo in 1993), Ichiro finally got his starting spot in 1994… and not only immediately won the first of three consecutive Pacific League MVPs, but set a league record in batting average with a .385 performance, winning his first of seven consecutive batting titles. The Blue Wave would then go on to win consecutive pennants in 1995 and 1996, as well as a Japan Series title over the Tokyo Yomiuri Giants in 1996. Ichiro was on top of the baseball world in Japan.

Yet Ichiro was restless. He was already looking overseas to Major League Baseball, and discussed it heavily. When it came time to renew his contract, he thought he would ask Miwata for his opinion, as he told Narumi Komatsu in Ichiro on Ichiro:

“He was the only person I could sit across from and really say what was on my mind.” But when Ichiro brought up the MLB idea to Miwata, “He just laughed it off. He wasn’t making fun of me, it’s just at that time it probably didn’t seem like a thought he needed to occupy his time with… I just thought OK, that’s the way it is. All of a sudden coming out and saying you want to play in the majors, it’s no wonder he laughed.”

Ichiro was on top of the Japanese baseball world. The team was winning championships. And in 1997, Miwata was rewarded for his hard work with a promotion, head of scouting. Everything was going perfect.

This is when everything falls apart.

Part 3:

After riding high for three seasons, the Blue Wave finally began to crash. In 1998, they posted a mediocre record of 66-and-66, riding .500 perfectly. The higher-ups were angry, something had to change, and it was on the shoulders of Miwata to fix it.

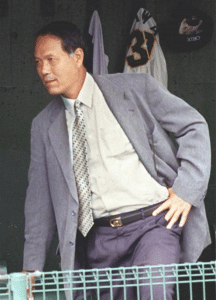

Enter: Nagisa Arakaki.

Although not nearly as famous as Ichiro, Arakaki turned a lot of heads in Japan during his high school campaign with Okinawa Prefectural Fisheries in Naha from 1995-98, with a demon of a fastball at 94 MPH, and a pretty decent slider to boot. Arakaki could help any pitching staff, especially one desperate to jump over the line of mediocrity.

Orix held top drafting rights in the draft meeting, and with their pick, selected Arakaki right out of high school. The problem was that, like Miwata 21 years earlier, Arakaki didn’t want to play with his the team that drafted him. The Daiei Softbank Hawks, managed by the legendary home run king Sadaharu Oh, also had the opportunity to pick him, and Arakaki made his stance: either the Hawks drafted him and he started immediately, or he’d enroll in university.

Arakaki was Miwata’s pick, and according to numerous reports, was crucial in Miwata’s plans to get the Blue Wave back in the pennant chase. Now, with Arakaki’s plans made clear, the pressure was on Miwata to sign his pick to a contract.

This was not exactly new territory for Miwata. Ichiro had originally been pressured by his father to join the Chunichi Dragons, but was successfully wooed over to Orix by Miwata. Miwata also had experience with the draft as a player, turning down his original offer from the Buffaloes in favor of joining the Industrial League. He was ready to take this on.

Except Arakaki wasn’t convinced. He saw no reason to head to Kobe and play for the Blue Wave, when he could get more experience at Kyushu Kyoritsu University and hopefully still eventually play for his childhood dream team and idol. Regardless of Miwata and how kind he could be, Orix just didn’t appeal to the young pitcher.

The executives, however, were not satisfied. They reportedly “ordered” Miwata to sign him, regardless of what Arakaki actually thought. Miwata was caught between two rocks: on one end, it was his job and he needed to get this done. On the other hand, it was unfair to force an eighteen-year old kid into a career and situation he didn’t feel comfortable in.

Miwata began showing signs of extreme stress: loss of appetite, lack of sleep, gaps in memory, as well as lapses in judgement. He finally came to a final conclusion: if he could convince Arakaki’s parents to influence him, then he’d finally have a bridge to the young pitcher. He arranged a trip to Naha, where Arakaki and his parents lived, in late November to make his ultimatum.

But it was too late. His parents could not be convinced, and Arakaki was already enrolling in university. There was nothing Miwata could do to change his mind, and the Orix executives were waiting for him back in Kobe. He felt trapped, and wanted to escape.

Instead of going home and facing his bosses, Miwata made a final lapse in judgement. He climbed to the eleventh floor of an office building in the city, took off his shoes and left his wallet, and ran through the window.

He was 53 years old.

Part 4

Miwata’s death, needless to say, rocked the NPB world. Arakaki was devastated, believing the death was because of his refusal, and even considered quitting baseball altogether before Miwata’s wife convinced him otherwise. On the other side of the conflict, however, the Blue Wave did not show the same level of compassion, with the team President at the time, Chongqing Izawa, saying that he didn’t think the team was responsible for Miwata’s suicide.

It must be understood that in Japan, the culture around the workplace is very different than in the United States. Business Insider wrote that death from long working hours, known as “karoshi,” is not uncommon. In fact, the Japan Labor Bureau (JLB) determined that of over 30,000 people who committed suicide in 1998, 6,058 of them were due to work-related stress – debt, poor business performance, or unemployment. “The Meaning of Ichiro” also notes this issue, with Whiting mentioning Miwata as an example.

When Miwata jumped in 1998, the Eastern Kobe Labour Standards Inspection Office opened an investigation to determine whether it was related to his job as a scout. Many reported they saw the aforementioned symptoms of stress (memory loss, sleep deprivation, etc.) as well as his work ethic, noting that he often held meetings at 6:30 in the morning.

Others, however, wrote that his death may have had more sinister overtones. In a book titled “Why the Famous Scout Died,” written a few years after his death, a friend from Waseda University wrote that Miwata was looking at a sum of 100 million yen in debt (about $935,000), due to the unfair practice of draft negotiations and how players may pick the teams; meaning, if the player does not sign with the team that drafts him, the team loses a considerable sum of money. The book was never published in English; only a few copies can still be found online.

When it came to passing a ruling on the suicide and whether or not it was related to his job, a decision was made in seven months; a time-period, the JLB noted, that was relatively quick compared to other cases and was made easier by the Blue Wave’s cooperation. They found that Miwata’s death was work-related, but not just in the sense of overwork; it was mainly due to the unique pressure he experienced in the position, one official announced. As a result of the ruling, Miwata’s family received the equivalent of $17,000 USD annually as compensation.

And for most, this is where Miwata’s story ended. For this story, however, there are a few loose ends to tie up.

Part 5:

First: Arakaki. As previously mentioned, the young pitcher was originally horrified with himself and pondered over quitting baseball altogether, until Miwata’s widow told him otherwise; he would go on to pitch for 12 seasons in NPB, with his start coming for the Softbank Hawks in 2003. Arakaki, however, did not turn out to be the star Miwata envisioned, as he lacked control and led the Pacific League in wild pitches many times, in addition to several devastating injuries.

Second: The Orix Blue Wave. The team was never the same after Miwata’s death, dwelling on mediocrity before finally sinking to the bottom of the Pacific League. The team would merge with the Buffaloes in 2004, but have yet to win another pennant since Miwata’s death. It’s been 24 years.

And last, but certainly not least, Ichiro. Ichiro would spend three more years with Orix before moving on to MLB, where he would begin his famous conquests in Seattle to become one of the greatest hitters the league has ever seen. And yet, he never forgot the man who helped him get there; when he was still playing, he would visit Miwata’s grave in Japan every year.

For Ichiro, Miwata was more than a scout. He was his friend, his mentor, someone who he could trust and reason with for both baseball and life as a whole. When Miwata leapt from the apartment building, he took with him the kind, loving personality that helped shape ballplayers into champions of skill and soul. He wasn’t the person who “discovered” Ichiro; he was the person who believed in him and gave him something to work towards.

And the baseball world was forever changed because of it.

For more baseball reading and updates, check out the rest of our Japanese baseball website!