This was a case of an “oops” moment eventually becoming “Yeah! OK!”

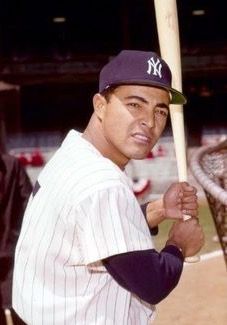

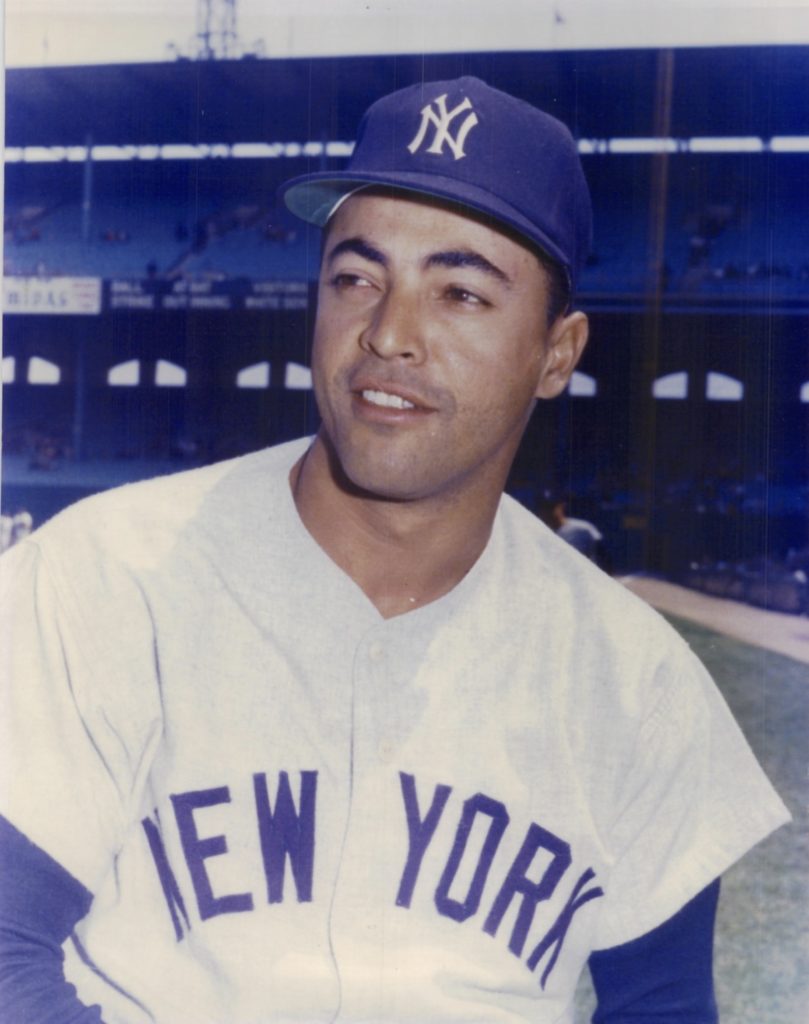

In early 1968, the Tokyo Orions (now the Chiba Lotte Marines) of Japan’s Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB) were in talks with the New York Yankees because the Orions wanted a Major League Baseball player to enhance their roster. The Yankees suggested “López,” and the Orions were delighted, believing the suggested player was Héctor López, a 12-year big-leaguer and valuable member of five pennant-winning Yankees clubs.

Except he wasn’t the suggested player.

Héctor López wasn’t with the Yankees anymore, meaning they didn’t have the right to negotiate his transfer. In fact, it had been two years since he donned the pinstripes, playing the previous two seasons in the Washington Senators’ organization.

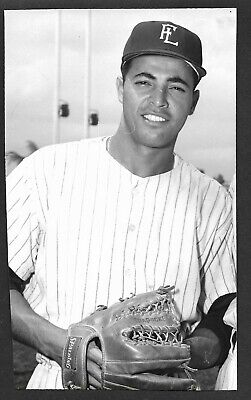

Instead, the Orions received and signed Arturo López, who hadn’t even played the previous season – save for 50 plate appearances in the Puerto Rican Winter League – but was still part of the Yankees’ organization, unlike Héctor. Arturo “Art” Lopez was the owner of only seven major-league hits in 49 at-bats, compared to Hector’s 1,251 over 12 seasons.

It was a classic instance of faulty communication, except the result was quite favorable for all parties, to say the least.

“I helped them save face” – The Orions’ Surprise Star

Arturo López, now 85 and living in Orlando, Florida, said the misunderstanding may have stemmed from when Tsuneo “Cappy” Harada, an influential Japanese American in baseball circles and a long-time member of the San Francisco Giants organization, helped Arturo connect with the Orions.

“I was playing winter ball in Puerto Rico and got a call from a Yankee scout [Pedrin Zorilla], who said the Yankees would be going with a younger group of outfielders, and asked if I would consider an opportunity in Japan. He asked if I’d rather do that or go to AAA, but I was married at the time and not interested in playing more in the minors,” said López, who’d spent six years in the minors and averaged .299 over that period. “So I asked if they would release me so I could negotiate directly with the Japanese. The Yankees granted the request and said that Harada would contact me.

“Cappy asked me if I could play third base, and, in my ignorance about how good Japanese baseball was, I said, ‘Yes, of course,’” López said with a laugh. “That’s probably where the confusion began.”

The first hint that something was amiss was that the López who arrived at Orions’ spring training was shorter than Héctor and, at 30 years old, eight years younger. And this particular López batted and threw left-handed while Héctor was a righty. Also, this López was exclusively an outfielder, while Héctor had amassed over 650 games as an infielder (in addition to outfield duties) with the Yankees and Kansas City Athletics. Another difference that perhaps the Japanese didn’t catch on to: Arturo was Puerto Rican, while Héctor was from Panama.

“I was the second-team manager at the time,” recalled Keiji Osawa. “We were planning on signing one foreign player. And when we brought over [the] foreigner, we realized he was the wrong player.”

Oops, indeed.

But the Orions couldn’t lose face by acknowledging the mix-up. “The culture in Japan would not permit [the Orions] to admit mistakes,” López said. The general manager at the time said internally, “If he isn’t good, we’ll just return him.”

“[In Japan], losing face is the end of the world. If you lose face, you become a non-entity,” López explained. “I don’t recall anyone ever telling me they had expected to get Héctor López. I just remember [teammate and former major-leaguer] George Altman alluding to it in a radio interview. But I got the impression they were kind of disappointed when I first got there. They had to have known because no lefthanded person is going to play third base. But they just put me in the outfield, and that was that.

“I helped them save face.”

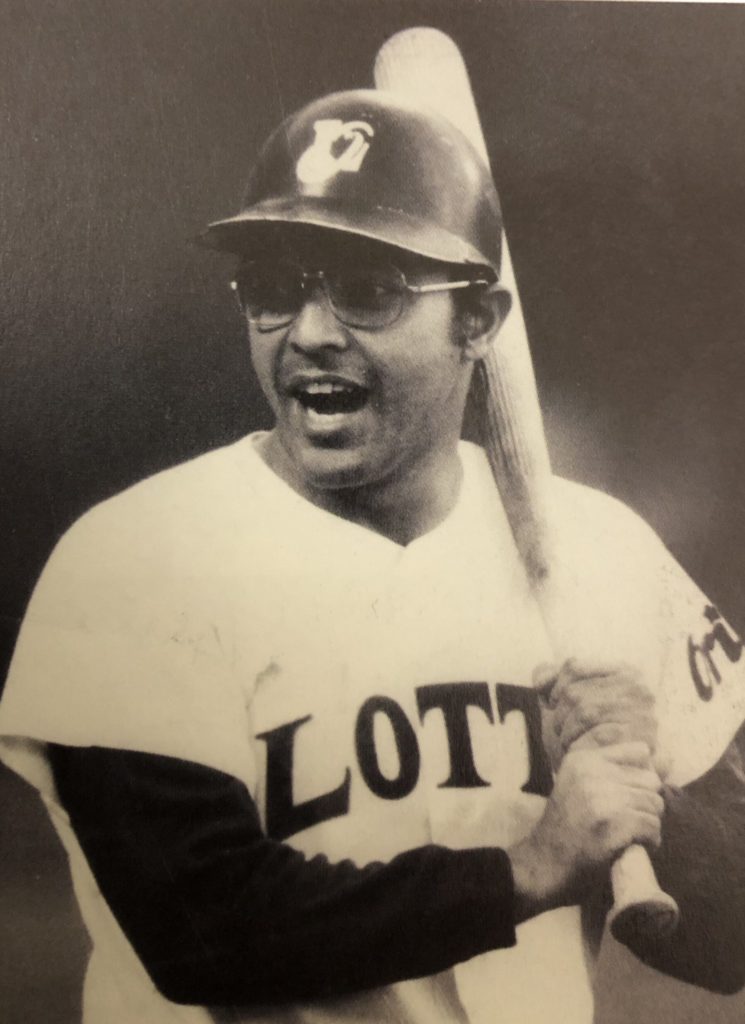

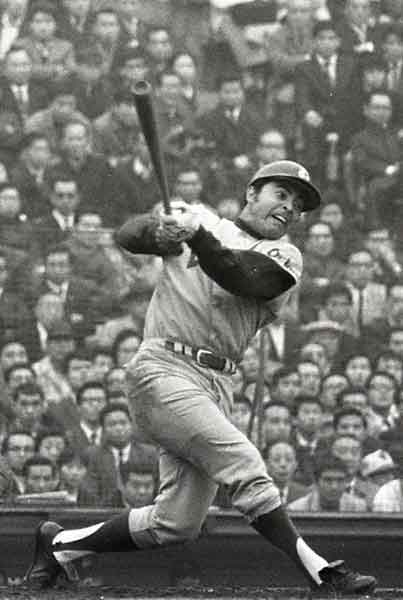

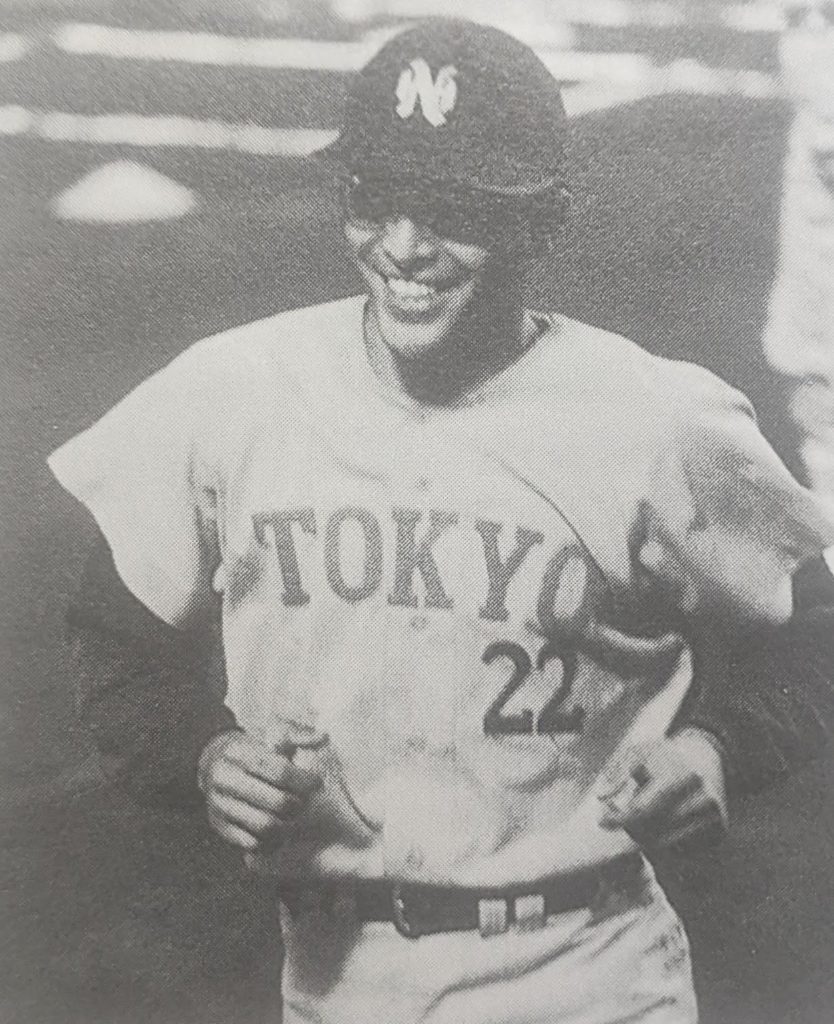

He did that first by working hard to adjust to Japan’s vastly different culture and approach to the game. Secondly, he was a solid performer from the start. In his first game, he tripled in the winning run, and he batted .289 that year with 23 home runs, 74 RBIs, and a .798 OPS. He spent four seasons with the Orions from 1968 to 1971, hitting for an even .300 average and eclipsing 20 home runs each year despite the shorter 130-game Japanese season. He then spent the 1972 and 1973 seasons with the Yakult Atoms (now Swallows), where his numbers started to decline as a 35-year-old, but he was still a contributor. In his six-season Japanese career, he averaged .290 with 116 home runs and an .804 OPS.

So, with apologies to the Rolling Stones, the team didn’t get what it wanted, but it got what it needed.

Adjusting On and Off the Field “I thought I was running all the way to Puerto Rico”

While the Orions didn’t know what to expect in López, López didn’t know what to expect in Japan. But his overall experience was certainly worthwhile.

“I figured I’d go there, have some fun, and make some money,” López recalled. When I got there, though, I sensed it was serious stuff. It took a year or two to adjust to everything, but it worked out well.”

To get to that point, though, he had to go through the typical adjustment period that all foreign players in Japan experience. And the differences then were perhaps even starker than now, 55 years later.

López likes to say he nearly starved during the initial 1968 season road trip because he and teammate Altman fiddled with chopsticks while their teammates picked up “great food from a huge bowl containing all kinds of fish and meats.” The [other] players ate a mile a minute, and the team bus was waiting, but we [Altman and López] had eaten almost nothing. It didn’t take us long to learn how to use those sticks to perfection!”

López was the first Puerto Rican to play baseball in Japan. His name had first been shortened to “Art” in the U.S. and then morphed to “Alto” in Japan to be more amicable to the local pronunciation. As a foreigner, he was always an outsider, with all that can entail. There are many cultural differences, and the Japanese game was much different, with more reliance on small ball than the big inning, larger strike zones for foreign hitters, interminable practice sessions with innumerable repetitions, and more.

“Integrating into the culture wasn’t easy because it was so different,” López acknowledged. “You’re not considered an equal. Here, a player like LeBron James has a lot of power and can influence management decisions, but it’s not that way in Japan. You’re inferior to the coaches. Here or in Puerto Rico, stars are special, but in Japan, they were just parts of the team. I didn’t understand that I’d still have to practice on off days even if I was leading the league in hitting. If I struck out, I’d get very angry, and the Japanese would think I was losing control. I wasn’t – I was just unhappy because I’d let the team down – but they didn’t see it that way.”

López remembers the practices, too – “When we’d do our running in the outfield, it was never-ending. I thought I was running all the way to Puerto Rico. I’ve got to say, though, that it was good in the long run. I was 36 when I retired, and I had an opportunity then to play in Hawaii. I turned it down, but I knew I could have done well because I was in such good shape.”

One example of the cultural differences particularly stands out. In 1970, López was having his best year from a batting average standpoint (.313 at season’s end) and was the only foreigner voted by the fans to the all-star team. The league hosted two all-star games that year, and López homered in the first one. However, he chose not to play in the second game because his wife delivered a son, Christopher, that same day.

In a reaction somewhat reminiscent to when Randy Bass took a leave of absence in 1988 from the Hanshin Tigers because his son was hospitalized in the U.S. with a malignant brain tumor, the Japanese press was less than understanding.

“I thought being at the hospital with my wife was more important, but the next day – June 19, 1970 – one of the papers ran a cartoon that showed my wife spanking me,” López recalled. “They were inferring that American men were henpecked. It was something we would laugh about, but, to the Japanese, it meant we were inferior.”

López says it took a while to fully adjust to the cultural and baseball environments.

“When I got traded after four years to Yakult, I saw that I was closer to the members of that team than I’d been to those on my first team. I had some great experiences while with Lotte, but I was sometimes too independent for them. Still, after the second season, I wasn’t a wild horse anymore, and I realized that, at 30, I probably did some things they thought were strange.”

Regardless, López produced. His 1970 performance helped lead the Orions to the 1970 Pacific League championship, their first title in 10 years. The team finished second the following year. “We had a great team,” López said. “We had a bunch of guys who hit at least ten home runs, and we once had a game in which the first nine guys got hits.”

The Beloved “Sun of Downtown”

There were perks to accompany the challenges of being a foreign player in Japan: the club facilitated private-school instruction for Arturo’s four children, the family lived in a nice house, and the pay eliminated the need to play winter ball. On the road, he and Altman stayed in the best Western-style hotels. Further, López said that the “Japanese respect your privacy; space is sacred.” After signing post-game autographs, fans let him walk to the train station, staying respectfully behind him.

Some unexpected perks came on the field too. López liked the smaller NPB stadiums and the Japanese style of making two cutoff throws from the outfield rather than one because these quirks made his less-than-stellar throwing arm less of a concern than it was with the Yankees. The smaller ballparks also helped his power numbers – López had only once hit more than ten home runs in a season before coming to Japan.

The comfort López found in Japan was apparent to the dedicated Orions fans. According to Japanese baseball history buff Daisuke Chihara, “the team played in a ballpark in downtown Tokyo, and he was quite popular for being very happy. He was called the ‘Sun of Downtown’ (Shitamachi no taiyō) because he brought brightness to the atmosphere.”

“All in all, it was a great experience,” López says now. “After my time there was over, I remember calling Héctor and thanking him. I said that I’d had a nice career in Japan, and it was due in part because the club thought they were getting him instead of me.”

Editor’s note: Check out the follow-up to this article, “The Right Path: Arturo López’s Life Before & After Baseball.” The follow-up article delves into his life after baseball, highlighting his continued lifelong learning journey, multiple academic achievements, and his impact as an educator.