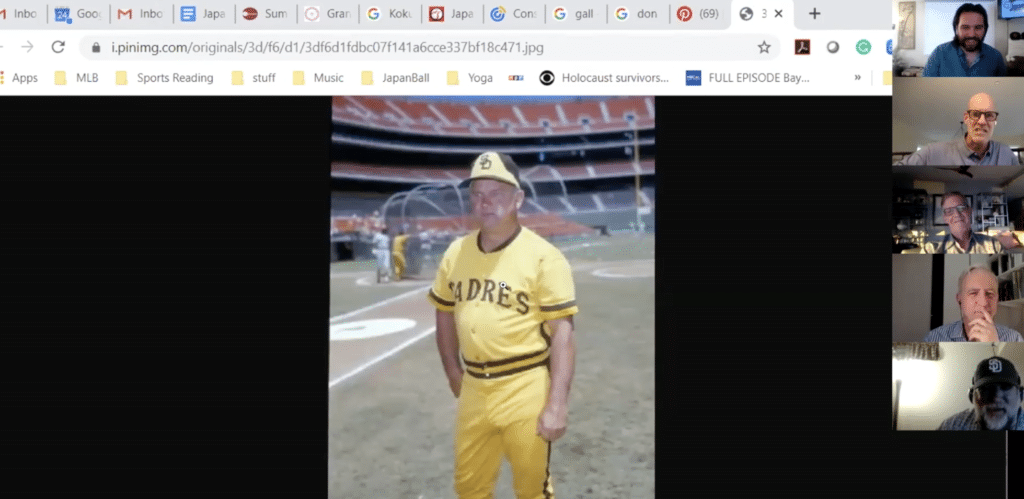

The Bavasi brothers are one of Major League Baseball’s best families, with their father Buzzie being a legendary trailblazer for the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers, and his sons, Peter, Bill and Bob, having high positions in the industry as well. On September 24, they joined JapanBall’s “Chatter Up!” with author Ken LaZebnik to discuss the writer’s book “Buzzie and the Bull,” discussing their father’s work with the Dodgers and relationship with famous role player Al Ferrara.

Shane:

Alright, so today, of course, we’re talking about Buzzie and The Bull with Bill [Bavasi] and Ken [LaZebnik] so let’s get into that. Ken, I’m going to start with you. Hey Ken, welcome.

Ken:

Great to be here. Thank you for having me, Shane, and thank you to JapanBall for being such a great group; I followed JapanBall ever since Bob Bavasi told me about it, and it sounds fantastic.

Shane:

Cool, we’re happy to have you, it should be a real treat today. So for everyone who maybe doesn’t know much about Ken, just gonna do a quick introduction of his background for everyone. So Ken grew up in Columbia, Missouri, a Cardinals fan down there, and he currently is back and forth between Studio City in LA and Brooklyn. He is a multi-talented author, playwright, humoris, songwriter, I believe… maybe not a songwriter, but he could if we asked. His talents know no bounds. You may have seen or heard his work in movies or on television, such as “A Prairie Home Companion,” “Star Trek Enterprise,” “Touched by an Angel,” etc, etc. He started a baseball literary quarterly called the Minneapolis Review of Baseball while he was in college, and that eventually became the “Elysian Fields Quarterly;” I wouldn’t be surprised if any of you here today are familiar with that, put it in the chat if you are, I’d be curious to know. And he’s written a couple of baseball plays too, which sound really interesting. One about Calvin Griffith, the owner of the Twins, and another one about the Angels Bullpen and competing for roster spots. Those are really fun. Currently, Ken is at Long Island University in Brooklyn, where he’s the director of their Masters of Fine Arts, in their television writing program, and he’s also busy writing plays and pitching TV shows. So Ken, once again, thanks for being here.

Ken:

It’s great to be here, especially with two of my favorite people in the world, two Bavasis. You can never go wrong when you’re paired up with some Bavasis.

Shane:

Yeah, exactly. I agree with that. I’ve been paired up with them too. It’s always a winning partner to have. All right, so Bill, I’m going to you now. Hey Bill, welcome.

Bill:

How are you, Shane? Thanks for letting me join you here. I watched your “Chatter Up!” with Sandy [Alderson]. And it was great fun listening to that, eavesdropping on Sandy.

Shane:

Yeah, that was a good one. Now he’s got himself a nice little gig with the Mets lined up here: President and maybe part owner. But anyway, thanks for joining us, Bill. I’m going to do the same thing here: an introduction of your background for those who don’t know. So, Bill is a baseball lifer, to say the least. As you know, if you read the book, he grew up around the Dodgers in the 60s along with his aforementioned brothers. He earned his stripes working in player development for the Angels, and eventually worked his way up to GM, where he held that post from ‘94 to ‘99. Then he was Farm Director with the Dodgers. In 2003, he became the GM of the Mariners, he was there until 2008. And then after that, caught on with the Cincinnati Reds to be VP of Scouting, Player Development, and International Ops. In 2014, he joined MLB’s Office of the Commissioner as Director of the Major League Scouting Bureau, and today he’s still at MLB as the Senior Director of Baseball Development, where his duties include, amongst many other things, overseeing the Arizona Fall League. I was lucky enough to have the opportunity to endure a few years working with Bill in New York and in Arizona, and he’s the first one who introduced me to his brother Bob, which led to me being here today. So thank you for that, and welcome to the show, Bill.

Bill:

Thanks for having me. I’m looking forward to him having some fun tonight.

Shane:

You’re welcome. You’re welcome. Bob [Bavasi], I got to go to you just for one second, so you can say hi to everyone, before we start here.

Bob:

Well, thank you guys, this is great. It’s so fun to see all these faces, I’m ready to go to the ballgame. I feel like we should gather in the lobby and hit the road. Let’s get on the train and go. It’s great to see everybody and Shane did this wonderful job with this, how fun this is and all the other items you’ve put together. So thank you very much.

Shane:

You’re welcome. Thanks for joining us, happy to have a couple of Bavasis. I should mention the other Bavasi brothers: Peter Bavasi, who was president of the Indians and the Blue Jays and the Padres, and then the fourth brother is Chris, and he entered the only profession more tumultuous than baseball executive, which is politics, and was the mayor of Flagstaff for many years. So I’m going to start with some questions. We’ll start with the book. To start off, Ken, I’m curious: What’s the origin story of this book, from your perspective? And what convinced you that it was worth writing? And I’m also curious, did you always want to write a book about baseball?

Ken:

Well, yes. It was Bob Bavasi that really was the start of this whole project. Bob and I have been friends for a long time. He happened to marry (very happily) a woman I went to high school with, Margaret Burns Bavasi. And so we got to know each other over many, many years. And I think, and Bob can correct me if I’m wrong, that maybe seven years ago, he said that following Buzzie’s death, the family kind of fully realized the extent of the friendship and correspondence that Buzzie had with Al “The Bull” Ferrara, and they had not fully realized how close these two really were. They emailed when email came to fashion, and would write each other notes and cards, and Bob just said, “you know, I think The Bull is such a terrific character.” As Bob mentioned in the preface of the book, oddly enough for somebody who grew up around the great Dodger teams of the 60s with [Sandy] Koufax and [Don] Drysdale and all those fantastic players, The Bull was kind of Bob’s favorite guy. And it was because of his charm and confidence and sort of wonderful fare-thee-well attitude that he carried both on and off the field. And so I met with The Bull, Bob arranged for us to have lunch together, and of course, The Bull is an amazing character with incredible stories. And so I said, “Oh, this would be a fantastic story.” And then it sort of evolved into, more fully, the story of their unlikely friendship, and ended up centering it around the year of 1965, which seemed to encapsulate a lot of the ups and downs of, in miniature, that The Bull went through repeatedly during his life. So it was a sheer delight. As you mentioned, I’d written a couple of baseball plays, which I always love, I’d written and edited the Minneapolis Review of Baseball, so the idea of writing a baseball book, and particularly one with this incredible history, was just a sheer pleasure. I ended up having the chance to sit with The Bull in his rather modest Studio City apartment every Monday for the better part of a year, and just talk to him. He has almost like a photographic memory for his life. It’s amazing, I would go and fact check or refer back to other sources and he was inevitably precisely right in his recollection of things. I think, and the Bavasis can correct me on this, this seems to be a kind of baseball player characteristic; seems like many ballplayers can remember very specific at bats. But The Bull remembers everything about his life, which makes it a great subject for a biography.

Shane:

Yeah, that’s really cool. And, Bill, how important, like to the family, was it that this book be written, [as] it’s obviously about your dad as much as it’s about The Bull.

Bill:

You know, when the project started off, it looked like it was something “for fun,” and I was going to be about Al (The Bull). And then Bob and Ken really kind of took it to another another level, [seeing] that this mixes with the telling of the story of our father, and that became really important to us. But it might have been Ken or Bob or whoever figured out that focusing on the ‘65 season, with the Vietnam War, and the Watts riots and everything that went on in ‘65, it’s just genius. Maybe we were too close to it, it’s really emotional reading this book. And at the start, if you grew up in LA and you can get through the first paragraph without at least shedding one tear, you’ve got ice in your veins, you’re not human. This is so well written, and so well thought out. We know it’s going to be well written because Ken’s a good writer, but to focus on the ‘65 season, that wasn’t all Al was, but it really was an important time for the country, the city and our franchise and our family; it was so spot on to hit that season.

Shane:

Yeah, I agree. You kind of touched on that, but one thing that was surprising to me or was interesting to me, was talking about the Watts riots. It really made me think a lot about what’s going on in this season, and it’s interesting seeing how some guys in the Dodgers were very directly affected by what was going on, not too different than what’s going on in this season. And Ken, I’m curious, how did you learn about the details of those stories and how the riots were affecting the team? Obviously, the way things are handled today, with those sorts of issues is way different than then.

Ken:

Well, fortunately, I was fortunate to obviously be able to talk to The Bull, although during that period in August, he wasn’t in Los Angeles, he would have been exiled to work in Triple A. But there are many wonderful resources and historical sources to go to, to research that particular piece of the story. There have been a couple of wonderful books; “The Last Innocents,” which focused on a group of Dodgers over the course of the 60s. And also, this is sort of the beauty of writing the history in this day and age, available online were complete additions of the Los Angeles Times and other local newspapers, which I was able to use as kind of more direct source material. Of course, the way they covered those days in August [was] very different than what we might see now. I think there is this strange parallel to this year, a year of incredible stress for the country and of Los Angeles being in a lot of stress, and baseball, and the ultimate triumph for the Dodgers in 1965, I think really did serve as a terrific tonic for that city, as it may do again, if the Dodgers continue doing as well as they are right now.

Shane:

Yeah. I wasn’t necessarily going to go down this line of questioning right away, but I guess it is a topical topic. It also reminds me, the part about Dodgertown and Vero Beach is interesting. I didn’t realize that Buzzie picked Vero Beach’s location, and also didn’t realize that part of the goal was to escape the kind of Jim Crow things that were going on, and for Jackie Robinson. Bill, I’m curious [about] what Dodgertown meant to you and to your dad and to the Dodgers organization, especially considering that history.

Bill:

Well, you know, somewhere on this call is our brother Peter, and if he rears his ugly head, you’ll get some good information on Dodgertown. He’s got way more than I do, or Bob. Bob might have been there more, I was only there once and I think it was ‘67 in the spring. It was obviously just a fascinating place, and so as a kid I really don’t have a ton to add except that it was a playground for us. It was just Mardi Gras every day for a kid, you had access to a golf cart and batting cages and fields and you could batboy for the minors. Our dad wouldn’t let us batboy for the Big League club, he didn’t want us around the Big League club much because they didn’t want the boss’s kids around too much, so he would really shoo us away. I ended up batboying for the Albuquerque team and got to know [them]. Dodgertown, It just had stuff like that going on, it’s just a great place. When Bob and I visited there. It was a barracks. It’s not the Dodgertown you see today, but I do know Buzzie told me that there was a train that went down down the coast and he stopped at Vero first; he was supposed to go on to Cocoa Beach or somewhere else, and was supposed to see other places. But he stopped in Vero, and saw they had everything that he needed, including a card game with [Bud] Holman. He was the mayor of the place. Again, Peter would have all these stories, but he just loved the place right then and saw that it was important. Also, Preston Gomez (third base coach with the Dodgers in ‘65) told me that it was important because there was a town right next to it called Gifford, and Gifford was a town that was all black. And so, what he would do is he would put up the black players in nice hotels there, and give them cars. They really took care of those guys if they wanted to go over there. And that was I don’t know any more details except that that Buzzie, and then Preston later on told me, that that was really important to those players was to have that town of Gifford right next door. Gifford now, I think there’s an elementary school that’s either called Dodgertown Elementary or something like that, but the O’Malley’s put a lot of effort in taking care of that school; they probably still do.

Ken:

And if I could add, this highlights Buzzie’s real, among his many, many accomplishments, he really was a significant participant in the Civil Rights movement in Major League Baseball. He was the one who, as Bill just said, in addition to sort of being a kind of founder, if you will, or at least discovered the site for Dodgertown and understood its importance of the geography of where it had to be, what it had to do. It had to be an oasis for the Dodgers, to have an integrated all club in a segregated south. But going back in history he was the the general manager at Nashua and was instrumental in the desegregation of the minor leagues when he started that club with [Don] Newcombe and Roy Campanella, and stood up for them during the course of that season. He was a very significant participant in the Civil Rights movement and Major League Baseball.

Shane:

Thanks for adding that. Peter [Bavasi], if you’re on, you’re welcome to speak up anytime.

Peter:

Just a story from me: Herman Levy was one of the top men in the Dodger organization, right at the bottom level. If it wasn’t for Herman Levy, Dodgertown would not have run like it did. Herman put the flag up every morning and took it down. And one morning, I remember as a little kid in the barracks, Mr. O’Malley, who got up quite early, was walking toward the cafeteria. And in came Herman with the flag, and he said in a very loud voice: “Good morning, Mr. O’Malley!” And Mr. O’Malley said, “Don’t give me that stuff, Herman, I know you’re after my job!” God, Dodgertown was a wonderful place. I remembered it being a place where 650 ballplayers assembled, so many players that they didn’t have enough uniforms with numbers on them, so they attached butcher paper with the grease pencil for the numbers and bobby pin them on the back of the jerseys. And I remember that, and the sliding pit over by the infirmary, and Andy High, who was the venerable chief scout for the Dodgers and the sliding instructor, would have sliding practice for all 650 of these guys, including the pitchers, a bent legs slide and “no diving please!” into this mess of shaved bark. And at the end of the day, and the sliding practice, Andy High would take Jimmy Campanis, Al’s son, and me kite flying. That’s what I remember most. I’m going to mute myself now.

Ken:

Well, he’s still unmuted and in honor of Herman Levy, my favorite story that I learned about Herman Levy, and it sort of sums up his eccentric, obsessive nature, was that one spring training, Mrs. O’Malley left a lamp in Dodgertown, and Herman boarded the bus, took a bus from Florida to Los Angeles, took a taxi to Dodger Stadium, delivered the lamp to Mr. O’Malley, and then just turned around and went back.

Peter:

That is a true story, and it’s a story that endeared Herman to everyone who knew him; all the players, the visiting players, the Dodger players, the staff. He was a former postal employee in Brooklyn, and he became attached to the Dodgers, he worked part time as a ticket taker. And then they put him over into the little parking lot to park the cars. And he didn’t have a driver’s license. And one day was a sellout, and Herman’s parking as many cars that he can, he’s got cars everywhere. And now the people come out looking for the cars after the game, and he had no idea where they were. He had keys just in his pocket. So he took the keys out, just put on the hood of one of the nearby cars and they took off; everybody managed to get their car.

Bill:

Everybody take a look at Shane’s face right now. Okay, so Peter is going off with a story, Bob’s going off with stories, I’m going off with stories. When I was working in New York, my desk was next to Shane. Shane is very nice right now, he’s got a good look on his face. When I was working with him, he got so sick of me telling stories over and over.

Shane:

It’s nice to hear a new story, it’s a rare thing. Although the one thing that we would always talk about is we’d try to nitpick where the story has changed every time.

Ken:

If I could involve Peter while he’s still unmuted. One of the things that I loved learning about, and never really occurred to me, was that the Brooklyn Dodgers moved to Los Angeles, and to a great degree, they take Brooklyn with them, that they have these eccentric sort of characters like Herman Levy who came to Los Angeles. And I always thought that was one of the great cultural transplants that I loved learning about, it was like taking Brooklyn and just plopping it down.

Peter:

Billy and I were emailing the other day on that very subject; all these wonderful characters from the Brooklyn/Los Angeles Dodgers who today would be unemployable because they are characters, and they’re not propellerheads, they have no interest in the metrics. They have an interest in staying at the ballpark, in the clubhouse all night long. Sleeping on the equipment trunks if they have to get the job done. Unemployable today. Shane, you’ve worked in baseball for a while, I think you know what I mean. You’re not gonna hire a Herman Levy.

Bill:

I don’t think so. Hey, listen, listen. Buzzie went to San Diego after the ‘68 season, and you did, and in the Expansion Draft could have had Steve Garvey, Bill Russell, Steve Yeager, but no, he takes Herman and Doc.

Peter:

Exactly right. Buzzie was great for his love of characters, and the book is all about that. Al The Bull was a character and Buzzie was very fond of Al for a number of reasons, not least of which were all of the character traits, the good, positive, solid character traits that made him a wonderful person and a terrific player as well. Great in the clubhouse, you’ll see the quote from his teammates in the ‘65 ball club, who admired him greatly. It’s just a wonderful tribute to Al, and he’s still around to read how his teammates felt about him. I’m sure Buzzie’s looking down on this and enjoying it as well.

Ken:

By the way, when I delivered the final, actual printed copy of the book to Al, then I called him a couple of days later, and he said, “okay, I’ve read the book. It’s the first book I’ve ever read.” And I actually believe him.

Shane:

Well if you haven’t noticed, on these calls when I have Sandy Alderson on, I’m not drinking a beer, but I’m drinking a beer today. So thank you guys for taking this one from me. But Bob Deal mentioned, he’s in Nashua, and they have murals and all those Dodgers guys up there. I thought that was an interesting part of the book. I definitely didn’t know much about it, but I think I mentioned this to Bob the other day, one of my favorite things was he went to Nashua, and the first thing he did is hired the editor of the local paper to be the President of the club, which is quite a savvy move and then also incorporated all sorts of other interesting and funny marketing ideas. [What’s interesting is] I grew up thinking, “Oh, I want to be a GM of a club one day,” and you have this idea of what it is nowadays, and it seems like it’s so different. And, Peter, I imagine when you were a GM, it was more of the old style, when you’re kind of in charge of everything in the business side. And so I’m curious, when did that transition happen? Did you have any of those sorts of responsibilities? And especially like when you work for Disney, did that affect your decision making? Or is it really just a baseball focus?

Bill:

So when does the General Manager become less of a general focus? That’s probably around the early 80s.

Peter:

As President of the Indians, you were responsible both for the operation of the business side and the baseball side. And you had fellows who ran the business side and also the baseball side, and then it got split, and rightly so; it got too complex. And so now what you have today, you have the President of the business operations and the President of the baseball operations. And, Billy, I think when you were at Seattle, you ran the entire baseball operations. Did you run marketing as well?

Bill:

No, no, I didn’t in Anaheim either. Dad was the last guy in Anaheim to do that.

Peter:

It was a tough job if you ran both sides to be effective with it. Just couldn’t be done.

Bill:

It’s just too much. And the GM job today, you’re seeing, it’s too much for one. They’re all hiring a President of Baseball Operations, and then a General Manager. I’m not sure the differences between a GM and assistant GM from that, but they’re just building up their staffs. And so I think mid-80s Shane, that was about the time that it changed. Bob Deal mentioned Nashua; that’s a great piece of history that Ken touches on in the book. And when I was with the Angels, we were affiliated in Nashua one year, and Buzzie called me and said, “Hey, I hear you’re in Nashua,” And I said “yeah, I’m here.” Now he said, “You know, Roy Campanella used to hit home runs over the trees in the outfield.” Bob Deal is the only one on this phone that can verify for me; the trees weren’t as big as they are now, they were just planted, but they grew. That is a beautiful setting for a beautiful ballpark.

Shane:

Bill, I was curious. I’ve heard a few things in the past about working under the Disney ownership. Even if you weren’t in charge of the business side, how much were you pressured whether in Seattle or in Anaheim? Like, how much did they kind of overstep or interfere with what you’re doing and make demands and whatnot?

Bill:

Oh, they weren’t bad. You know, with Disney I’m kind of proud that I was a GM for two years, and then they bought the club, and I didn’t get fired. That’s not that common. It’s really not, it’s pretty uncommon to hang around for another four years with a new owner. But they were actually real fair, real good. And the President of the club, Tony Tavares, realized that, “hey, we’re gonna have a tough time with this. Based on the baseball rules, we should be trying to emulate the Expos, target .500, and see what goes from there. He prepared a presentation from Michael Eisner, who was the CEO of Disney, and the presentation was to show them, “hey, we should cut the payroll back. We should do this like Montreal Expos.” And Tony put a lot of time into this, a lot of time and we went up to Burbank and made the presentation. Michael Eisner listened, and he said, “you know, Tony, I really appreciate what you’re doing. But we’re not doing that. We’re Disney.” And so he turns to me and says, “Who are the top free agents in the market?” And I said, “well, Mo Vaughn and Randy Johnson.” And he said, “Okay, I want you to go get them and don’t come home without him.” And so I got one of them and couldn’t get the other one, because Randy Johnson was not a [fan] in the American League. He was shrewd enough to know, you know, the American League is just a butcher shop because of the DH, and all the offenses were real tough then. And so he went to the National League where he was smart enough to get himself to the seventh hitter, and then make his way around at the top of the order. But so he wasn’t coming to Anaheim. He was leaving our league. In Seattle actually had a similar experience when Kuroda was coming out in Japan, he was coming out as a free agent and the owner in Japan said, “hey, go get that guy and don’t come home without him.” And I went to Japan for a week and spent a lot of money just taking people out to dinner and schmoozing. And after the second day, I knew we weren’t going to get him because he was being helped by Shigetoshi Hasegawa and I had signed Shiggy in Anaheim, and we became pretty good friends. And he said, “hey, it’s not going to happen here, man. This guy’s wife has seen Rodeo Drive. He’s going to LA.”

Kevin:

Hi guys. I’m really enjoying it. Kevin Lamp, brother of Dennis Lamp, who played 16 years.

Bill:

I thought you were Dennis Lamp when I was looking at you!

Kevin:

I’m a lot better looking than him. What I was going to tell you was, my dad had gone to the Chamber of Commerce to listen to Buzzie Bavasi while my brother was pitching at St John’s High, and people were saying, “you’ve got to lift weights!” And my dad went up to Buzzie and said, “What about pitchers lifting weights?” And he said to my dad, “When Sandy Koufax starts lifting weights, we’ll all lift weights.” And then the other one was the first Dodger game. My dad grew up in Brooklyn, and the first Dodger game I went to I was nine, and The Bull pinch hit for Drysdale in the eighth inning, and there was no hits in the game. There was an error and a walk. And Al Ferrara, on my birthday, May 15, 1965, hit a three-run homer in the eighth and beat Dick Ellsworth.

Ken:

Yes, that was the highlight of Al’s ‘65 season and one of the highlights of his career, was breaking up that no-hitter and he did with an injured hand! He had actually injured his thumb, but sort of took off the bandage because when he was asked, “Are you ready to hit?” He said, “Absolutely.” and went up there. And it was a wonderful, wonderful day for him.

Kevin:

You know, one other thing. Dennis gave up Lou Brock’s 3000th hit. You know, he just passed away, and it was a line drive off his fingers. And somebody asked him afterwards. “What about it?” He said, “I guess they’ll be sending my fingers to Cooperstown.”

Bill:

I saw that video the other day when he passed away, I was looking at all the videos of him. And I saw your brother. And when he brought us the stolen base record, it was in San Diego when I was on the grounds crew; I got to pull the bag for him.

Kevin:

Oh, wow. And what about your dad? Correct me if I’m wrong, but he didn’t re-sign? He didn’t re-sign, Nolan Ryan, and he said “I wouldn’t pay a half a billion dollars for a .500 pitcher.” Is that a true story?

Bill:

It’s true he didn’t sign him. I recall him saying “hey, at his record, we just have to sign two 8-7 pitchers,” and he took a lot of heat for that one. But after Nolan’s last no-hitter Buzzie sent him a note and it just said, “Dear Nolan, Okay, I get it already.”

Ken:

The Bull also had a memorable appearance on Gilligan’s Island. Again, something you would never see today, him and Jim Lefevre. They played headhunters dressed in costumes that you would never get away with today. And he was also in the Batman TV show in the 60s, playing one of the nervous henchmen. Actually Dennis gave him a hard time, “how many people you know got beat up by Robin.”

Shane:

Hey, Kevin. Thanks for that. That was good stuff.

Bob:

Shane, Joey here has asked a question about who are some of the players that Bill or Peter worked with that were sort of “The Bull” types. And one of the things about the book that we came to appreciate was really sort of wondering, what did Buzzie see in Al? What was it that he saw in him? Because he clearly wasn’t an everyday player. And you know, today we have the minor leagues being cut back. Much different than the Branch Rickey thing where out of quantity comes quality. So I was just sort of wondering about that today, you know, would The Bull have been in the ballclub? What about that, in terms of the way they looked at players then and the way they look at players now, and Billy, you’re probably closest to that. I’m curious what you think?

Bill:

I think he would, because I think his numbers were actually okay. But you know, it’s hard to say because it was a feel thing. If Dave Dombroski ends up in Anaheim, you’ll see some “Bulls” there. And it’s weird, but you know, you kind of have to have guys like Al that can take a hit, they just can take just bad breaks, but keep coming back. Peter’s had them, Buzzie had them, they’re hard to find. And they’re hard to find, guys that can just sit there for quite a while. Early on in the book, you kind of make that point that you sit there for five days, and you’re in an athletic endeavor, and it’s a game as much as it is a sport because there’s so much hand-eye coordination. I think there is still value in that, they might just look at them a little differently. And I don’t think there’s ever going to be a meeting again, like you described Bob, or somebody says, “Yeah, he’s good on the club, keep him.” There’s going to have to be more to it than that, and it’s going to come down to more analysis. I don’t have a great answer for that. I think those guys do have value in any walk of life, And I want to add to the point that Bob made early in the book that he was good on the club. And then you were talking earlier about the country in ‘65 and now; I will say that what the country can use now as a bunch of now is The Bull, because in your story about him stopping off at the driver’s house in the Dominican, I know what those houses look like, and nobody just walks in them. It’s not a place you’re used to. And Shane knows that, Shane lived there for a couple of years. And that doesn’t faze guys like The Bull. His friends were from every race, every ethnicity, didn’t see color, and the world could use a lot more of Buzzie and The Bull.

Ken:

Yeah, I totally agree. And I wanted to sort of salute Bob, because Bob was really instrumental in forming the thinking that’s represented in the book. Buzzie had to have teams that were inhabited by players with nerves of steel, because those Dodger teams of the 60s, they never were, like, 2-1 games. They were always 2-1, 3-2; they relied on players who could come through in the clutch. And that quality, and it’s noted by so many of The Bull’s teammates, this intangible quality [of] what somebody brings to a club, is something that had real value, even if you couldn’t score it out in a sabermetrics matrix. And interestingly enough, by the way, as you’re referring to this 2020, very strange baseball season, truncated, it has occurred to me that that same quality of player might be extremely valuable in this particular season. Because you’re in a very bizarre season, where coronavirus is kind of hanging over everything. It feels as though it’d be very valuable to have that kind of “Heart of Gold” player that would know that “we’re in a tough situation, but I’m going to keep everybody’s spirits up. And I may sit out for five games but I’ll be ready if I get called on to pinch hit in that sixth game.”

Shane:

Yeah, I agree. I have to say though, you’re saying you don’t think anyone will ever pick a player for “oh, he’s a good guy. We’ll keep him on the team.” One interesting thing I read was when a couple of these teams have won the World Series recently, or when any team wins the World Series, they talk about how great of a clubhouse it was, right? And there’s people who are trying to quantify clubhouse chemistry and they look at, “okay, what is the team projected to finish based on all the numbers?” And then if they overachieve, who are the common players over the course of their career, their teams constantly overachieve. And it’s like a super intricate analysis, I’m sure it’s in a lot of ways unscientific because how could you possibly quantify it? And it’s funny that some of the quants out there are saying, “Oh, actually, maybe there is something to this,” whereas Buzzie would say “he’s a good guy.” He knows immediately. He knows he’s got the feel and instinct, and he’s like, “that’s the guy I want on my club.” Now the more statistically minded guys out there are trying to figure out how to wrap their math around clubhouse chemistry.

Bill:

Don’t bother. If you do that, then you wouldn’t have the Oakland A’s of the 70s that won three World Series in a row; they almost killed each other.

Peter:

Today, you cannot have bench jockeying. You get suspended if you taunt the other players, right Billy? It’s too quiet now in the ballparks where they’re playing today, and players are being suspended for taunting and sticking their tongues out at the opposition. I don’t know if any player in the 50s and the 60s could survive on a club where you had no bench jockey. And then you can also get suspended if you pitch inside; you don’t hit a guy, you don’t even knock them down, you’re pitching inside? Eight day suspension. Don’t get me started.

Ken:

Hey, can I ask a question for the Bavasis here, because one of my favorite things that I never really fully thought through was the kind of miraculous thing that Buzzie did in rebuilding the Dodgers to win the 1959 World Series. And I think Buzzie very graciously, he was the only General Manager to win a World Series in Brooklyn, 1955. So Branch Rickey, you know, for all of his genius, didn’t win a World Series, Buzzie did. And then his club was aging, they moved to LA and they had a pretty bad year in ‘58. Right? And then, he managed to totally turn it around and win and rebuild this team and win a World Series in ‘59. And just, to me, we’re talking about general managers, the job of General Manager; that to me is like this amazing accomplishment that I’d love to hear maybe and maybe Peter remembers that year.

Peter:

I do, and I remember Buzzie explaining that he had spoken to Mr. O’Malley about the composition of the club that they were going to bring to the West Coast. And it was decided, not for artistic reasons but for financial reasons, to put the club on the field in LA the first year that was a club from the old [Brooklyn] Dodgers so the fans in LA could see that, but Buzzie knew that that club was not going to win. And so the next year he had all of these players in the pipeline ready to go, even in ‘57. Anyway, he tells that story that it was a strategic move to build the roster that way. Billy, you remember it that way?

Bill:

Well I was three. I had looked back on it because I love the history of it, and he always said that was his favorite team and you got that ring, and I know it was your favorite team or one of your favorite teams. I just know that to Ken’s point, you know, that was kind of an astounding turnaround. And that’s all I can really say about it because I didn’t live it. I know what Ken knows about it. That is it is a remarkable change from being a power hitting team to one that was so tactical defensively and pitching wise. It was just amazing that you can come to Hollywood and write that script. You know, come in there, show them all the “Boys of Summer,” gas them, and then come out with a championship team.

Peter:

It had to do with scouting, right? It was scouting, good scouting, you don’t have scouts any longer. The propellerheads run the scouting department. But back in the day you had wonderful scouts all over creation. Buzzie had a scout in Chicago, a wonderful old scout whose only assignment was to go and watch the Cubs, and the White Sox when the Cubs were on the road and the White Sox were playing home. And he would watch both clubs, both leagues. And if he saw somebody he’d like, he called Buzzie and say “get this guy!” and Buzzie wouldn’t even ask him what the attributes for the player.

Bill:

And Ken, you actually covered that.

Ken:

Yeah, what I loved was this notion that in the same way that you fill a ball team, you cast the ball team; I’m sorry, I’ve – being from TV thinking, it’s not like casting the ball team. You cast a writers’ room with people with different attributes. What I seemed to be gathering was that Buzzie would, if you will, cast a scouting team of scouts, each of whom had different attributes, each of whom had different styles and different abilities. There was also the parlor scout.

Peter:

Leon Hamilton! He was the parlor scout! After the draft came in, it was the luck of the draw, but back in the day, the territory scout would find a kid and then Leon would go in and sign them. And Leon, sometimes if it was a single mom running the family, he’d take her out dining and dancing and whatever it took to sign this kid he would. And one time, one of his baseball associates said, “You know Leon, that is a very clever way of signing these players, where you go out dining and dancing with the mom and you sign the player. One of these days you’re going to make a mistake, you’re going to sign the mother and you’re going to take the kid dancing.”

Ken:

My other story about Leon Hamilton was that apparently one of his techniques was to go to a hardware store, buy like a 100 pound bag of cement, put it in the trunk of his car and put some of his shirts up in the car, pull up to the to the prospects house and then tell the parents “Hey, look, I’m headed out of town. You got to sign now or else I’m out of here. You can see my car is totally packed up.” And then and then they would sort of panic and say “okay, all right, we’ll sign” and then he’d go return the bag of concrete to the hardware store.

Shane:

We’ve got some people with their hands raised. So I want to get to some of these questions before we fall into that more. All right, Ian, I’m going to go to you here.

Ian:

So I have a couple of questions for Bill and one for Peter Bavasi. So Bill, I’m a big Mariners fan, and you talked about Hiroki Kuroda. So was it really just his wife liking Rodeo Drive? Was that it? And also, how close were the Mariners to acquiring Johan Santana. Like, was there really a movement? Like I’m guessing it had a no-trade clause for the Mariners. And then for Peter, what was it like being a teenager and being around the 1955 Dodgers, and how happy was your dad when they won the World Series?

Bill:

So on Johan Santana. While I was there, we weren’t very close; there was nothing ever going on with him. But maybe after I left, but nothing was when I was there. And then [for Kuroda],

I can’t really tell you. I will promise you it wasn’t money, because nobody would outspend us for him because the owner in Japan. One of his dreams was to have the first all-Japanese battery, that’s why we signed [Kenji] Johjima. Somebody asked a question earlier if ownership ever made demands, that was one of them, because Johjima is not a good player. He was not good enough to sign in the States for as much as we gave him, he’s certainly not good enough for an extension, but it was important to the owner and he owns the club. So you try to keep him happy, and the fact is, if that’s what he demands, you kind of have to do it, so we made the effort to sign him, and we did. But Kuroda, he wanted to have the first all Japanese battery, and we would have probably paid anything and so it wasn’t money. And, you may not like to hear this, but there are some Japanese players that when they go to a team in the states, they don’t want to be with another Japanese player; they want to be the Japanese player there. And then… Ichiro intimidated him, because he was so good, so fast, so famous that he did intimidate some of those guys. I’m not saying Kuroda was that guy, but I will tell you that what was not money and it wasn’t for lack of effort.

Peter:

That is some fantastic inside baseball info. I never heard through the analysis of the Japanese players not wanting to be on a club?

Bill:

Well I will tell you though, I do want to add and to make sure I’m clear on this. They respected Ichiro like crazy. I’ll tell you two things about Ichiro. One is that for a seven o’clock game, he was never there later than noon. And he wasn’t showing up at noon to play cards in the clubhouse. He was showing up at noon, and he started working. And one of the things he would do is lift weights, he’d stretch. Also, we had a masseuse for everybody, but he was mostly there for Ichiro. And it’s the style of massage that he gave this guy, it looked like torture, it didn’t look enjoyable at all. And this guy ended up working on Ichiro one day pressing so hard, and Ichiro would kind of tell him: “more and more and more.” This guy broke his own rib, putting enough pressure on Ichiro. I remember because I heard about it, I went downstairs and I talked to the guy; I don’t know if you’ve ever dislocated or broken a rib, but there’s nothing good about it. And this guy was in real pain, and I had actually been here before, dislocated my rib, and I wouldn’t have worked, but he went ahead and I talked to Ichiro. I said, “Hey, we’re going on the road, we’re gonna have to get somebody else for you, you know?” And he said, “No, he’ll be okay.” And I said, “What do you mean he’ll be okay?” He said, “he’ll be okay.” And that was it. And I turned to the masseuse and he said “I’ll do it.” It was just one of those force-of-will things. When I first saw Ichiro, same as you all when you first saw him, I’ve only seen two guys change the game, and that’s Bo Jackson and Ichiro. And Ichiro made teams shift and change the way they play, and I’ve never seen one hitter change the field as much as Ichiro, and I’ve never seen a player scare guys as much as Bo Jackson. And I think Harold Reynolds put it best one time he said “I was taking a throw for the third out across second base. I took the throw, stepped on the bag and I’m going to the dugout, but just as I step on the bag, Bo Jackson slides in.” And he said “I’ve never heard anything sound like that. The sound of him sliding in,” he said, “I knew I’d never get in this guy’s way.” But anyway, Ichiro and Shigetoshi Hasegawa, I’ve never seen anybody more prepared to play a baseball game than those two guys.

Ian:

Can you just talk about Ichiro’s ‘04 season, just because you were there?

Bill:

I was always amazed by every year he had. So I got there in November of ‘03, and I talked to the manager, Bob Melvin. I met him in Arizona and he said, “You know, this guy can hit .400. And there’s no doubt in my mind. He really should get .400 but you watch what he does this year.” And so I watched him and he said that he had talked to Ichiro about it, and the most important thing to Ichiro was that he felt he could help his team the most if he got 200 hits every year, and he felt he had to get 200 hits every year. And so if you ever can, I don’t know what the resources are, but if you can look at video of him, you’ll see him foul off ball four a lot, because he wants to. And he could do that. And he’s one of the only guys you’ll ever see do that. But for some of his teammates, it annoyed them, because for them, if he can get on first, if you watched him in ‘04, nobody ran better than this guy in the American League. So I mean, he could do it all. He had the best arm. He ran the best. He was the best hitter and if you ever wanted to, he’d be the best power hitter too. He should have been in every Home Run Derby there was, because he can hit every pitch out of the ballpark if he wants during BP. And for him, it’s part of his routine. But the ‘04 season, I didn’t have a whole lot to compare it to beforehand, except what I had seen, the same everybody else saw. I was just a fan watching from LA. But the ‘04 season, I’m not sure I’ve seen a better player ever.

Peter:

You mentioned the conditioning that Ichiro went through. We sold John Sipin, the infielder, from the Padres, to the Yomiuri Giants, I think years and years and years ago. And when John came back to the States, we were having the winter baseball meetings in Hawaii, and I had lunch with John and I said “What’s it like playing over there?” And he said, “It’s conditioning. If you don’t work hard, and if you don’t condition, you’re not going to make it over in Japan. That’s the problem with a lot of the American players, the gaijin players, is that they don’t understand that it’s all about conditioning.” So I don’t think that would surprise any player who played in Japan to see what Ichiro goes through.

Bill:

I will say Johjima had gotten past his prime, and he came over here, and he was prepared. He was in shape, he was conditioned, he was prepared and he hit real well his first year, he did some things okay. But just, his skills had deteriorated enough. And you know, the other guy that I did not get to see play because he retired right when I got there was [Kazuhiro] Sasaki, the closer. Shiggy was fit and was finishing up but you know, those guys, they all are conditioned physically and mentally. The guys that come over from Japan, they see it as such a challenge.

Mark:

All right. Ken, did you discuss Al Ferrara having a big part of Tom Seaver’s 19 strikeout game, and I believe he struck out the last 10 batters, and he was the first batter to strikeout in that streak, and the last one. The reason I know it, I was 14 years old, I think it was a late afternoon game and it was like 50 years ago, and I was watching it on TV, and I just remember that. Did he have the only hit that got the Padres the run as well? I don’t remember, but I know that he had a big part in that game.

Ken:

Yeah, I remember asking him about it, and he wasn’t terribly eager to talk about it. I don’t think it was a pleasant memory for him. You know, he’s very competitive, and he was a ballplayer who wanted to win and he never wanted to be remembered. Even though he had a lot of fun and humorous things, sort of, about his career, I think my impression was he didn’t want to linger on that particular day too much because it was somewhat of a bitter memory, I think.

Duff:

Hey guys, first of all, I want to thank the Bavasis for helping get to baseball in San Diego, I’m a huge Padres fan. And with us finally in the playoffs again, my main question is, I believe for Bill, wasn’t San Diego your first actual baseball job?

Bill:

It actually was. The first job I had, Peter alluded to, was for the traveling secretary and head trainer for the Padres, and I worked for his brother, Al, who ran the stadium, not the stadium operations, but the ushers. And so I worked for him for a few weeks, and then somebody on the grounds crew called in sick and he said, “Hey, you want to fill it on the grounds crew tonight?” I said yeah, so I did. And the next night, he said, “Hey, do you want to keep doing this, because the guy quit?” So I kept that, it was my first real job. I stayed there, did that for a few years, actually. But that’s just a seasonal job, and in San Diego, the grounds crew was union. So they worked eight in the morning until five and then knocked off. And then dopes like I, I came on at five and just line the field and drag the field and cleaned up the BP stuff. It was great fun though, it was really a lot of fun, because the grounds crew had a little dugout, next to the home dugout, and there’s an alleyway between them, there’s a door that goes up the alley to the corridor to the clubhouse. There’s a bathroom there and a drinking fountain, and the players kind of hung out in that area. And some of them would hang out in our dugout, and sit on our Cushman cart. And I think that is the precise area where Bob saw Al The Bull, waiting to go to the on-deck circle, sitting in a chair with a bat between his legs and smoking a heater and just getting ready to go. Bob, I’m gonna let you finish, if I think that’s the precise part. But that was a great job. That was one of the best, most fun jobs I’ve ever had.

Duff:

I’ll let him finish. The second part with that is, what was it like finding your way in baseball with the Padres being a brand new team, you know, just getting your feet underway, they didn’t have a winning season for like 10 years. By the same token, it had to be fun working in that environment, just trying to get things started a little earlier today.

Bill:

I’m gonna let Peter answer that and Bob, they’ve got way better recollections than I do. And Peter should have written a book by now about his time with the Padres. So Peter, take it away.

Peter:

Well, I went to San Diego with Buzzie as the Farm Director. I had been several years over in Albuquerque as an apprentice, learning the business end of baseball, I worked for a wonderful man, Elton Schiller, who ultimately became the business manager of the Padres. And so my first recollection, Judy and I and our two kids know- I guess we just had one child at the time- We’re very excited about coming over and Buzzie was very excited until though he found out not too many months later, that C. Arnholdt Smith, every nickel we deposited for ticket receipts, Smith would take out the other end, and so we were bouncing checks all over town. And this continued on until Ray Kroc bought the club and got us back from Washington, where we were gonna end up. So for us, for Buzzie and my mother but Judy and me and our kids, and I think for Billy and Bobby, they were of age, our life with the Padres began when Ray came in; that was really the beginning of the Padres for us. The early years, they were a lot of fun, because we didn’t know any difference. None of us were making any money, first of all, so whatever Smith was doing with the club coffers didn’t bother us at the time.

Bob:

Let me tell you about making money. So this is what it was like working there. So Billy’s on the grounds crew, I get out of college and I go to work in the minor league department, working for Mike Port. Mike’s the Farm Director. There’s a guy who’s working in the ticket office who’s going to take the month of August off to get married, and the ball club was home like 22 days. So Buzzie says to me, “hey, when you’re done working with Mike, I want you to go work in the ticket office.” So I’d go, I’d be done at five, I go down, I’d sell tickets. And then on weekends, the club was home three weekends by the way, I would work in the ticket office, and it was mind-numbing work, because there were no computers. If somebody ordered 200 tickets, you pulled them out of the vault, you had to count them; therefore there was no daydreaming. So it was really hard work. So about two weeks into this, I go in to see Dad, I said, “Hey, you have a minute?” “Sure son, come on in. What’s going on? I said, “Well, you know, I just want to ask you, I’m doing two jobs, and I think I should get a little bit more for that.” And he says, “Really? Well. Let me ask you. Are you doing your job well?” “Yes, I am.” Are you doing his job well?” “Yes, I am.” “Well then,” he says to me, “seems to me, I don’t need one of you guys.” That’s baseball.

Ken:

Bob, I would love for you to say; one of my favorite stories is how you designed the San Diego Padre hat when you were like in high school or something.

Bob:

Leon or someone will know what year this is, but so mom and I are at a General Managers’ meeting and walking through some room and there’s the uniform guy. I see the New Era guy, and they have a black and white sort of hat with a triangle in front. And I said, “Hey, could you make that in brown and gold?” And the guy says, “Sure.” So I said, “Well, can I borrow that?” And I said later in the day, “Hey, Dad, can this be our hat?” He goes, “Yeah, sure. Go ahead.” So then I figure I’m on a roll, and you know, it’s the 70s, everything’s very cool; Oakland’s got these crazy uniforms. So then I come up with, “hey, well, maybe we should make our uniform kind of hip and cool.” And so in my mind, hip and cool was this mustard colored uniform, that I’m just so totally embarrassed by. But he said, “Yeah, sure. Go ahead.” And so you have a high school kid designing uniforms. There you go.

Bill:

That hat you did, that was like the most expensive hat in the history of baseball, because if you take a look at it, and you google Don Zimmer, you’ll find a picture of him in that hat, and the Braves the same year did something similar, but they just had the two front panels white because that’s cheaper. We actually had that in an overlay that went back to here, it was nuts. And I remember asking Ray Peralta, “Hey, this is nuts! This thing weighs a ton.” He said “That thing cost a ton. Shane can’t even believe any of this because he has seen what the winter meetings are now. That was back when you went into a hotel room and you saw New Era’s exhibit, but we had no money. I do want to say though, also to Peter’s point, and Bobby’s point and the question; going through those years, and now seeing what it takes to have a ballclub, the fact of that club is still in San Diego is amazing. The fact that Buzzie and Peter and that whole group kept that thing alive. If you go to the Nationals’ ballpark in DC, they have an area that’s wallpapered with baseball card images, there’s a bunch of Washington Padres; it says Washington so they’ve got the pictures. Topps had already produced the set of cards for that year. And so the Padres were Washington, and they were gone. I think Peter, you were looking for a place to live. The idea that that club is still in San Diego was just a great operation, they just did such a great job.

Peter:

I was sent to Washington by Buzzie, I stayed at the old Shoreham Hotel, and my job was to set up the offices and facilities over at the old RFK Stadium. And every night I would have dinner usually with a sports columnist for the Washington Star, and I thought of a brilliant scheme using Buzzie’s technique in Nashua. I said to him one night, “Give me a hand on this. I think I’m going to gather up all the media here in town, and they can select or help me select the manager.” He says “no, no, no, that’s not how it works. Here’s how it works. you appoint him, we knock them.”

Shane:

That’s awesome.

Peter:

And then two weeks later, I was called back because Ray Kroc came in and bought the club.

Bill:

Thank God.

Judy Bavasi:

Can I talk? I have a story about those. After we found out that the club was bankrupt, and we were waiting for somebody to rescue us, Buzzie sold a player so that he could pay the staff, because we had a new home, and we had a mortgage to pay, and there was no money in the Padres coffers and Buzzie sold a player so that we could pay our mortgage, and the rest of the staff got paid. He was just that way. Great.

Ken:

Which was also, by the way, why Al The Bull ends up getting traded to Cincinnati?

Peter:

Yeah, for Angel Bravo and $35,000 that’s the money that you’re talking about. The 35,000.

Shane:

All right. I’m gonna go to John Kohl for another question.

John:

You mentioned later, I didn’t know that [The Bull] didn’t play in the ‘65 World Series, because I’m learning in July. But I was looking at the ‘66 World Series, because I’m from Baltimore, so the Dodgers played the Orioles. And he’s the only guy in there that’s got a perfect 1.000 batting average, he had one at-bat in the fourth game of the World Series, and I was totally blown away that that was the only World Series appearance he ever had.

Ken:

Yeah, and it’s a testament to Al; He finally got in the World Series game, went one for one, got a hit as a pinch hitter, but really, he was about winning. What meant something to him was being part of the ‘63 World Championship team and being on the ‘65 World Championship team, just not eligible to play in the series. I just sort of asked him about that experience in ‘66, and for him, because they lost, it wasn’t great, it wasn’t a great experience. He’d rather win. He’d rather not get a chance to hit and be on a winning team.

Bob:

You know, what’s interesting, though Ken, in the ‘65 season, where he was banished for a while and he comes back too late to play on the World Series team. The ballplayers voted him a full World Series share, even though he did not play the full season in Los Angeles, and because of the rules he was not able to play in the World Series… that, I think is the highest testimony to his value to that ballclub, that the ballplayers were to give him a full share.

Ken:

Yeah, and as he noted, and we note in the book, the poignancy that he really feels, is that in that era, if you weren’t on the World Series roster, you did not receive a World Series ring. And I don’t know, Bill would probably know this, nowadays I gather that it’s sort of a courtesy that generally people get a ring if you are affiliated with a team. I think it really saddens The Bull that he doesn’t have a ring from that ‘65 World Series.

John:

I don’t know if Ken mentioned it, but he went down to Spokane when he got in trouble, when he got arrested. But I just looked at the stat and he played 41 games for the Dodgers and 63 games for Spokane but he batted .307 in Spokane even though he was sent down, that’s how good of a ballplayer he was.

Ken:

Yeah. And he was also very proud of the fact, as he should have been, that a lot of players, especially in that circumstance, ugly circumstances, you know, “you’re never going to play for the Dodgers again. Go off to Spokane.” Other players would have taken their time to get there. But he got there the next day and was playing. He was always a guy who, as I say in the book, he had this characteristic gesture. He doesn’t hang on to the past. That old Cherokee proverb of “don’t let yesterday take up too much today,” he really believes that. I think he intrinsically has that notion of “I’m not hanging on to the past. I’m moving on.”

Mike:

I grew up in Temple City, California, about 10 miles from the ballpark, and ‘65 was the first season I really followed the team as an eight year old, all through Vinnie. I had two parents that really didn’t know much about sports. So the next year they finally took me out to a game, and the second game we went to was in September against the Astros on a Saturday day game. Ten inning game, it was 0-0 and The Bull knocked in the winning run. I think Drysdale pitched the whole game, and might have been a pinch hit, but a base hit to win the game and my dad, an Italian guy, said, “you know that’s gonna be your guy, Ferrara,” and he was the next few years. The next year… The Bull hit 16 home runs, we thought that was just such a big number in 1967. And ‘68, early in the year, went to bat day, and I think my sister got The Bull’s bat, and I got Bob Bailey and I made her switch with me. I used that bat the rest of Little League season in 1968. And then just recently, the last few years through horse racing, I got to meet The Bull and got a chance to talk with them and stuff. But I have a question for the Bavasis; growing up in Temple City, in fifth grade, my teacher was Carol Seidler, whose brother was married to Walter’s daughter. So the first day of fifth grade in 1967, we had to write what we did in the summer and I wrote a scathing note about [Maury] Wills being traded to Pittsburgh, blaming Mr. O’Malley. But I wonder, what was your dad’s role in all that? Did he try to try to talk the owner out of it? And any insights on that little incident?

Peter:

I remember that Maury didn’t want to go to Japan for the postseason exhibition, and this annoyed Mr. O’Malley who was a great proponent, Shane as you know, of expanding baseball over into Asia, which was not the case at the time. And Maury being a great star, he was expected to go and he didn’t, and I think that didn’t sit well with Mr. O’Malley. I think that might have been part of why he was invited to leave.

Bill:

I remember that it happened. I don’t remember any details any more than what I’ve read. I do remember where I was when I read that he was traded. And I was trying to remember where I was when they were talking about Drysdale and Koufax holding out; I don’t remember where I was when Kennedy got shot, but I remember where I was when those two held out.

Shane:

Mike, you used a big league bat in Little League?

Mike:

It was a 31. And I remember in a Little League All Star game with the big crowd with The Bull bat, I hit a ball off the wooden fence.

Peter:

The first year they had in Dodger Stadium, when they had the bat day, they gave the kids the bats coming in, and they almost busted up all the concrete and so yeah, every other bat day it was on your way out.

Ken:

The Bull always said to me repeatedly that the greatest offensive threat, the most potent offensive player he saw was Maury Wills. He said, “I know I played against Willie Mays and Roberto Clemente and all these great players.” He thought Maury Wills, during that time in the 60s, was the most potent offensive player that he ever saw.

Mike:

He’s great, loved him when he came back.

Shane:

That was really fun. Thank you all, thanks to all of our guests, and our special guests, our uninvited guests, the other Bavasis. All of you are always welcome. I got through about 10% of my questions, but I’d have it no other way; that’s what I was hoping for. So thank you all so much for joining and Leon suggests Bill or Bob, I don’t know if either of you want to give a quick pitch before I give some pitches on Scout School. I think some people on this call might be interested to hear about it.

Bill:

So a buddy of mine, Bob Fontaine, whose father worked for Peter in San Diego, great scout, and Bob on this call and Peter on this call, you know a lot of us have kind of made a living based on scouts just doing a great job in the game. And guys like me who can’t scout, who don’t really know what a player looks like, have to be told by a scout, and so there’s so many of them that are not working now that we wanted to start something where we could involve them with fans again. So we started a scout school. We don’t market it, we haven’t really pushed it, although someday I think it’s gonna be something but the first year we had 19 people show up in in Arizona in the fall; the second year, we had 40 people show up and then this year, we aren’t going to have an in-person scout school. But we’re going to have to do it online for five days for a couple hours a day starting October 17 through the 21st. And you can find that on the website, thebaseballbureau.com. Thanks, Leon and Shane. Thanks for, this was so much fun, I love talking baseball with groups like this, we don’t really get to do it. We’re working on this stuff so much. We don’t see the forest for the trees. And it’s just fun to talk. It’s fun to talk about baseball.

Bob:

Thanks for this. This is a wonderful forum. It’s great to see all these JapanBallers here, men and women both that I have gone to Japan with and thanks so much for this.

Ken:

Thank you Shane and all the Bavasis. What a treat. What a delight. This is why writing this book was such a sheer delight.

Shane:

Ken, great work and Bob, thank you for making this happen. Thank you to all the Bavasis, Judy included, for joining us. We had a great time. And for anyone who doesn’t have the book, and if you’re not convinced yet then I’m not sure what it would take, but you can go to althebull.com and buy a copy for yourself; of course, it’s on Amazon and everywhere else as well. Thank you all again!

For more “Chatter Up!” check out our YouTube channel for the full discussions, or our website for more transcripts and recaps!