One of a city’s most prized features is its sports teams. Whether it’s the stadiums located in the middle of busy neighborhoods or the parades tearing up the streets after a big championship win, a sports team and its city go hand-in-hand, often becoming a central part of one another’s identity. Just see the Cubs in Chicago, or the Packers being literally owned by their fans in Green Bay.

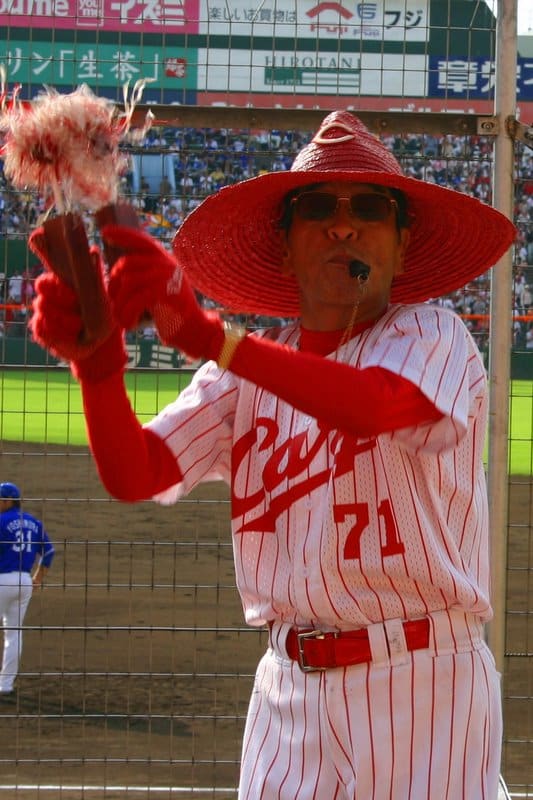

There’s no difference in Japan, as fans often bleed passion for their beloved baseball teams, whether it be diligently memorizing each player’s official song or stubbornly cheering with passion until the last out, even during a blowout loss. When it comes to the most passionate fans in Japan, however, many agree that the best fans in the country belong to the Hiroshima Toyo Carp; the fans pack the stadium every home game with a sea of red, and one can’t go two blocks in the city without seeing a team logo, whether it be on a citizen’s clothing, on a restaurant’s walls, or even on the manhole covers of the city’s sewer system.

How did this happen? What made Hiroshima fall so in love with this team? To answer this, we need to go back in time to the team’s creation, and the darkest period in the area’s history: late summer, 1945.

Part I:

When the United States dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, it not only decimated the region but brought a period of suffering and toil as well. It’s estimated that between 90,000 and 140,000 people died as a result of the bombing, and the city was completely destroyed. What’s more, the predicted effects were harrowing, as it was estimated that plants wouldn’t grow in the region for over 75 years and the city’s children would grow up in an area full of lingering radiation.

And yet, the people of Hiroshima kept going. Three days after the bomb fell, the streetcars continued to run, and the local newspaper, the “Chugoku Shimbun,” printed its daily reporting, with help from other papers in the region. While the factories, castles and homes were destroyed, the people kept moving, and began to reconstruct.

Meanwhile, the Japanese Professional Baseball League kept moving as well, growing and gaining influence across the island. In 1949, they began making plans to expand, creating two separate leagues and allowing up to seven new teams to join their ranks to fill out the new divisions. This caught the eye of Chugoku Shimbun president Go Kawaguchi, who quickly began planning.

Before the bomb dropped, Hiroshima was widely known as a baseball haven in Japan, featuring several stellar high schools in the national tournaments and gaining a lot of attention as one of the most talented prefectures in the country. Even after the war, baseball continued to be an essential part of student life in the region, and Kawaguchi recognized its universal appeal. With NPB’s announcement of expansion on his mind, he realized that not only would it help bring money into the region, it would also provide healthy entertainment for a populace desperate for diversion.

With his goal set, Kawaguchi met with several important figures in the prefecture, including prefecture official Yoshinobu Kono and members of the local bank and railway, to discuss his idea; he was met with support, but told he needed to create an official plan before they would fully commit. If he could put the plan in place, the Prefecture government, along with the local cities in the region, would support and invest in the team, and even supply a small stadium for the team. Now all they needed was a founder.

Enter Naboru Tanigawa.

Tanigawa’s tale is interesting on its own, as he was an ousted politician who desperately wanted to help his hometown recover. He had won election to the House of Representatives, but was expelled due to his connections with the Imperial Rule Assistance Association, a group that wanted to push the effort of total war during WWII. Looking for opportunities, he accepted the role as Chairman of the Founding Committee, and told Kawaguchi he’d help him. The two presented their plan to the government, and received investment from Hiroshima Prefecture, as well as the cities of Hiroshima, Kure, Fukuyama, Onomichi and Mihara.

They tossed around Bears, Pigeons and Rainbows, but wanted to make the name relevant to the region. They looked to the local geography for inspiration and honed in on the Ota River, known well for its vast amounts of native carp fish. What’s more, the bomb had destroyed one of the most important historical structures in the region, a castle built in the 1590s known as “Carp” castle. Tanigawa chose the name, and asked Kawaguchi to promote it in the newspaper. On September 28, the first official mention of the Carp was made in the paper, and the company was founded as “Hiroshima Baseball Club,” with support from local businessmen as well, like Hiroshima Electric Railway president Nobuyuki Ito.

With the people getting excited and the government behind them, Kawaguchi presented his plan to NPB commissioner and Yomiuri Shimbun owner Matsutaro Shoriki on November 28, 1949, and officially got approval for a team in December of that year. The area was ecstatic; finally, they would host a professional baseball team of their very own.

Of course, first they’d have to put one together.

Part II:

Now that Hiroshima was officially part of NPB, they needed to find players to actually compete, and a manager to lead them to glory. They wanted someone local, someone who could relate with the struggle of the city and the passion of the hometown, and lead a team to greatness.

Shuichi Ishimoto was that man. When high school baseball was formally organized in the 1920s, he returned to his alma mater and managed the team to two Koshien national championship tournament victories, in 1929 and 1930, making the school a powerhouse. He left the team to become a legendary manager for the then-Osaka Tigers, and bounced around multiple teams in the decades that followed. When Kawaguchi approached him with the challenge of building a team for Hiroshima, he accepted almost immediately, and told the founders he would build the team himself.

Although Hiroshima being a new team in Japan was certainly neat, it also meant the team had no existing network of players to use, and that Ishimoto had to build the team from scratch. He relied on his network of Hiroshima natives and former high school stars, asking them to come back to Hiroshima and be part of the best the city had to offer. Of course, they couldn’t afford any established great players; it was a team of misfits that were playing for pride and barely a salary.

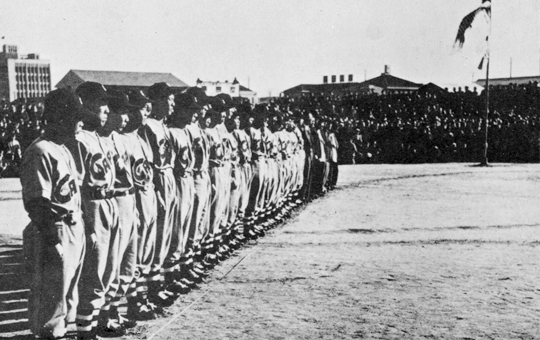

But they had a team, and on January 15, 1950, the team was officially introduced at Hiroshima Sogo Ground Baseball Park in front of 10,000 adoring fans. They would begin play in March of that year, but the ragtag team struggled, winning just 41 games and losing 96; at the end of the season, they’d finish 59 games behind the first place Shochiku Robins.

Their mediocrity, however, was not good enough for the league, and posed an immediate problem for the Carp. Unlike modern expansion teams, they could not rely on home ticket sales to buoy their business. In 1950, NPB had a rule that regardless of who was home or away, the winning team would always receive 70% of ticket admission sales, while the losing squad would receive the rest. Although this rule would be removed in 1952, the Carp were leaking money, and with no official corporate sponsor, they had no funds to fall back on. As a result, players on the team would go months without being paid a salary.

What’s more, NPB was not letting them get away with this easy. The Carp were dodging payments throughout their first season, even their own league membership fee, pushing the due date three years back to try to make the cut. At the end of the season, they were 6 million yen in the red. They tried to get companies to invest, but no company wanted to take the team on. When it came time for the team presidents to meet in March before the 1951 season, the team was derided by the Central League officials, famously declaring: “Professional Baseball is not something you can do without money. Why don’t you sell yourselves immediately?”

They almost did.

Part III:

It was considered almost a certainty the team would collapse on itself, and after being seriously reprimanded, a deal was made to force the squad to consolidate with the Taiyo Whales in Yokohama. Desperate, Kawaguchi and Ishimoto once again took to the Chugoku Shimbun, writing that if the citizens could just band together and help, maybe the team could be saved. Ishimoto also went on record in front of the Hiroshima Prefecture, passionately declaring that “if the Carp is removed, there will never be another local team in Hiroshima.”

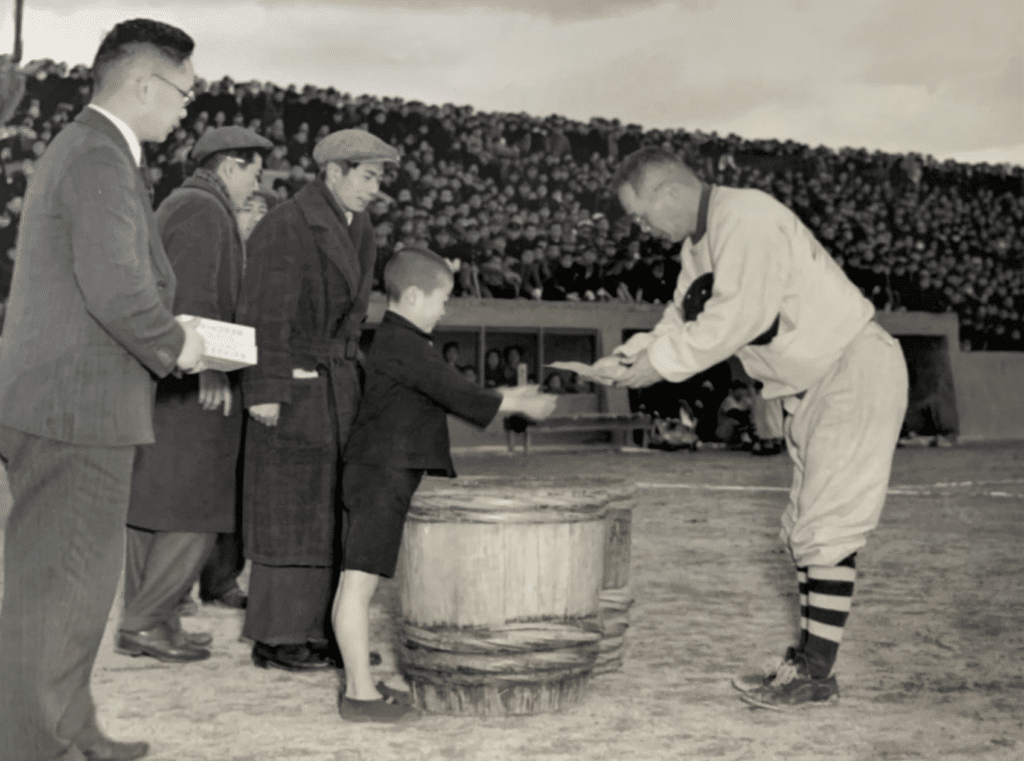

And thus, the Hiroshima Carp Support Group was formed. Despite still being in financial recovery after the bomb and having almost no economic prosperity to spare, the Hiroshima natives banded together and donated money for the team’s success, even placing it in large sake barrels placed outside the stadium grounds; the team also went door-to-door across the region after games, with star players asking for donations, even sometimes singing songs to the fans.

The gambit worked, with 4.4 million yen raised by season’s end and the support club going 13,000 strong. Despite a mediocre record of 32-64, the Carp would play another year, and the region was now a permanent part of the team’s lore.

Unfortunately, the salvaged season still could have been their last. The odd number of seven teams in the new Central League was a headache for league officials because it prevented them from being able to perfectly schedule all the games in sync. As a result, the league came up with an idea for the 1952 season: any team finishing with a winning percentage below .300 would be removed from the league and combined with another team.

The Carp put their backs against the wall from the onset, as they went on two losing streaks of seven games to start the season. At the halfway point, they were 13-46-2, almost guaranteeing the desperate fanbase that they would lose their beloved team. But like a Hollywood movie, the Carp somehow kept finding a way to win. They didn’t exactly catch fire, but went 24-34-1 to finish the season 37-90-3; a whopping .316 winning percentage! They had played well enough to stay alive.

Meanwhile, the pennant winners from two years prior, the Shochiku Robins, went 34-84-2 for a .288 winning percentage, and were combined with the Taiyo Whales. The resulting Robins outcasts led to the Carp fans pleading with management to try to sign the free agents; when the ownership responded with the usual “we have no money,” the fans responded by raising an astonishing 14 million yen to sign players.

And with that, Hiroshima became a permanent part of NPB.

Part IV:

While the Carp were no longer in danger of contraction, it would be years before they would find financial stability.

In 1955, the Carp found themselves in trouble again, as the debt accrued had grown to over 56 million yen. Toyo Kogyo president Hajime Matsuda, whose car company was a huge part of the rebuilding and redevelopment of Hiroshima following the tragedy, came up with an idea so crazy it just might work: bankrupt the company and push the properties onto a new corporation. Although they would risk losing their players, the team would be able to restart with no debt. Kawaguchi accepted the proposal, and re-founded the team as “Hiroshima Carp Co. LTD,” with the local railway president, Nobuyuki Ito, helping once again as president.

Some in the league protested, saying that the team should have to surrender its assets and players, and the team should have to repay their membership fees. At the Central League meetings in December, however, Kawaguchi spoke to legendary Central League chairman Ryuji Suzuki, as well as four of the six team directors, and asked them to be sympathetic towards the plight. They agreed, and announced to all that the new company “was just a name change.”

The Carp would never be in the red again because in 1957, 10 local companies invested 160 million yen for a new stadium to be built just outside the Hiroshima Peace Park and monuments, permanently tying the team to the reconstruction it brought after horrible destruction. The Carp opened Hiroshima Municipal Stadium on July 24, 1957 with a night game against the Hanshin Tigers, and crushed them 15-1 in front of 15,000 ecstatic fans.

Eleven years later, Tsuneji Matsuda became the majority owner of the team, and inserted his company name into the team name: Hiroshima Toyo Carp. He didn’t remove the city name, however, as he knew how important the citizens’ support was to the history of the team. The Carp began to grow, gaining more players and support, and soon featuring a new color on their uniforms: red.

Finally, in 1975, with the emergence of star players such as Koji Yamamoto and Sachio Kinugasa, the Carp became one of Japan’s premier teams and won the Central League pennant. Although they didn’t win the Japan Series, the Carp fans still went nuts for their team’s success, holding a parade with over 300,000 fans in attendance. As the parade drove down Peace Boulevard, it could be seen that the city had fallen completely in love with the Carp, a team that, like themselves, had struggled through the post-war times, built itself up with the support of their neighbors and friends, and put themselves back into the forefront of Japan. The city, and their team, were ready for bigger and brighter things.

And they were; the team won back-to-back Japan Series titles in ‘79 and ‘80, along with another in ‘84.

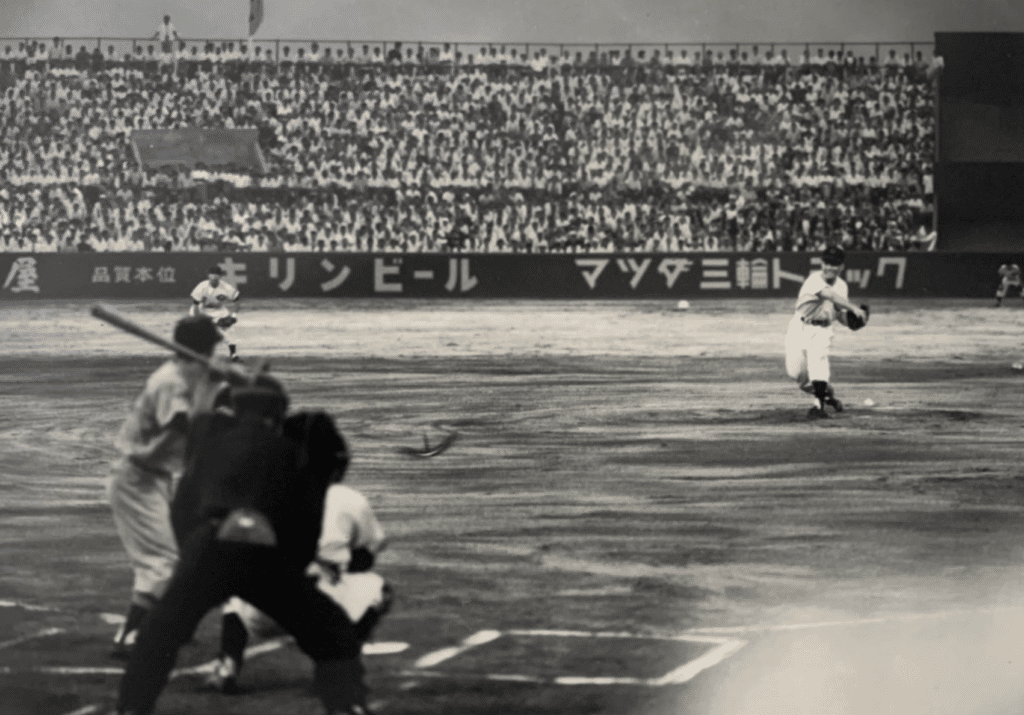

Editor’s note: eager baseball fans noted that we left out the Carp playing the Dodgers during the latter’s 1956 tour of Japan. The city was still recovering at that point, so the Dodgers visiting was a big deal for both the team and the region. The Dodgers would leave a bronze plaque to remember the visit, and they would end up being Jackie Robinson’s final games with the Dodgers.

Part V:

The Carp nowadays are known as one of NPB’s greatest teams, as they won three straight pennants from 2016 to 2018, feature superstar outfielder Seiya Suzuki, and play in Japan’s newest stadium: Mazda Zoom-Zoom Stadium, a modern ballpark that can seat up to 32,000 rowdy fans.

Of course, while the stadium is perhaps NPB’s best ballpark, it’s not the most important site in the region. The Hiroshima Peace Park, built as a tribute to the horrible losses of 1945, is one of the world’s most tragically beautiful places, and every year over a million people from around the world visit to pay respects to the great tragedy. The Carp, who played just across from the park for many years, are no different; every year on August 6, the team pays tribute to the many lives lost on that day in 1945, whether it’s with moments of silence or wearing special team jerseys that show the unity of the city.

The ruins of Hiroshima’s Prefectural Industry Promotion Building, known as the “Atomic Bomb Dome.” The Carp played just across from the structure for years.

The Children’s Peace Monument in Hiroshima Peace Park. Countless origami paper cranes fill the displays behind the statue of Sadako Sasaki.

Memorial Tower for Mobilized Students recognizes the approximately 7,000 school children who died in the bombing while assisting with civic efforts to fire-proof the city.

Wide view of the Hiroshima Peace Park. Millions of visitors from around the world visit annually to pay their respects and support the park’s goal of ending nuclear arms.

The team was born from the ashes of the region, it was raised by its hard-working citizens, and it eventually found success through its struggle to just stay afloat. The team is a testament and contributor to the spirit of Hiroshima, building themselves up from poverty with nothing but determination and help from their neighbors. It’s truly one of the greatest stories of sports and human spirit.

There’s nothing like baseball.

For more Japanese Baseball History, check out our website! For other great places to see a game in Japan, try our list of the Japanese ballparks ranked!

5 comments

Very nice write up on my beloved Carp.. 🙂 .. thank you.

You’re welcome, Hugh. Thanks for reading it!

Great article; you guys are doing a great job in expanding our knowledge of the Japanese game and it’s history

Thanks for the compliment, Frank. We are happy to spread the word on our beloved Japanese game!

Number one carp girl Suzuka nakamoto. BABYMETAL