Officially, JapanBall started 25 years ago, but the groundwork started much earlier.

For starters, go back to when founder Bob Bavasi was growing up in a family whose patriarch was Buzzie Bavasi, long-time Los Angeles Dodgers general manager, later president and part-owner of the San Diego Padres, and even later executive vice president of the Los Angeles Angels. It was an immersive baseball experience from a very young age. The family’s intercom system would pipe Vin Scully’s Dodgers broadcasts to all the rooms in the house; players often came by their home; and Bavasi and his siblings spent many hours at the ballpark.

Then there were the few years after college when Bavasi worked in the Padres’ front office. Then came law school, but always with the idea of applying the degree in some way to baseball. Next was the purchase of a failing, unaffiliated minor-league baseball franchise and making a success out of it. Later, there was a stint on a community college’s board of trustees, through which he met Mayumi Nishiyama Smith, who directed a program at the college providing Japan studies for Americans and exchange programs for American and Japanese students. That led to a trip to Japan, which eventually begat the idea of taking groups to Japan to experience baseball.

So, in essence, it was a case of seeds dropping over a long period of time and eventually becoming JapanBall.

“Different things just kept building on each other,” Bavasi agreed. “All these provided knowledge and skills that I could apply when the concept for JapanBall became a possibility.”

More detail is in order.

As noted earlier, Bavasi is from a true baseball family. Brothers Bill and Peter have spent many years in the game, as well, including stints in senior management for multiple MLB clubs.

“Baseball is a family disease,” Bavasi has often said.

Bob has just followed a somewhat different track. After getting his undergraduate degree in 1976, he spent a couple of years with the Padres and then chose law school. With free agency then very new in baseball, and seeing that not many in the game knew how to deal with it, he thought having a law background would help.

It did, and came with the added bonus of meeting his future wife, Margaret. A fellow law student, she was researching a paper on labor arbitration in sports, and a colleague referred her to Bob.

“I met Margaret on one of my rare trips to the law library. Unfortunately, I didn’t have much for her . . . but at least I got a date out of it,” Bob said wryly. They eventually had two daughters, one now a lawyer and the other a physician.

He graduated in 1980 and had a whirlwind first week – graduating, passing the bar, getting sworn in, getting married, and making his initial court appearance in just six days.

“Insane,” he says now.

For three years, the two spent intense hours practicing law – Bob as a trial attorney in civil litigation and personal injury and Margaret focusing on labor law. But, as Bob said, “My intent was always to get back into baseball.”

Ron Frazier, another law school friend and now a superior court judge in San Diego, recalled a time when the two were taking a class in contracts.

“I said to Bob that this was great – that we were learning so much that we could eventually put into practice,” said Frazier, who went on a JapanBall tour in 2015. “But Bob said, ‘I’m not going to practice for long.’ I said something like ‘Huh?!’, and he said, ‘Right – I’m going to own a baseball team.’”

That happened in late 1983 when the couple purchased the struggling Class A minor league team in Walla Walla, Washington – then one of just two U.S. minor league teams not affiliated with Major League clubs – and moved it to Everett, just north of Seattle, for the 1984 season.

Bob recalls brother Peter telling him that their father thought he’d lost his mind, particularly since most minor league clubs at the time were money pits.

“I had seen an article in The Sporting News about a guy who had bought the team in Nashville and three other clubs and was actually making money, which was unheard of then,” said Bavasi, who was just 29 at the time. “I talked to Margaret about it, and we finally said, ‘Let’s do something stupid.’

“It was just a wild, stupid idea at the time and it turned out well for us,” he added. “We had a great run and did OK when we got out. Although I’ve never had baseball owners call me and ask how to become a lawyer, I’ve had plenty of lawyers ask me how to become an owner.”

A lot of people thought that putting a team in Everett was a bad idea because it was only 30 miles from the Seattle Mariners’ home ballpark, but the Bavasis made it work by focusing on the fan experience – something Bob carried over to JapanBall and his later ownership of a collegiate summer ballclub in northern California.

The two were involved in every aspect of the operation, down to roaming through the stadium, talking with fans before and during games, and working the concession stand. They introduced a variety of activities to make the games fun, such as having the club’s groundskeeper put on welding goggles, a pork-pie hat, suspenders, and shorts and race a fan around the bases during the middle of the sixth inning.

Frazier was able to attend a game during the Bavasis’ first season owning the club, and he received the honor of throwing the first pitch.

“Bob introduced me as a two-time wrist-wrestling champion from Iowa,” Frazier said with a laugh.

Bavasi says, “The personal touch is very important. That’s one thing that makes people want to come back. My mission was not to watch the game but to make sure that YOU had a good time watching the game. So JapanBall fit with my psyche.”

Bob and Margaret tried different ways to get involved with the community, and Bob was eventually invited by the governor of Washington to serve on the Everett Community College (EvCC) Board of Trustees, of which he later became chairman.

Through his work on the board, he met Smith, a faculty member and program director of Nippon Business Institute and Japanese Programs at the college. Bavasi said Smith and others would travel to Japan each April, visit a few colleges, and pitch them on sending students to Everett for the summer session when enrollment was low. EvCC was also a sister college to what was then Toho Gakuen Junior College (now Aichi Toho University) in Nagoya, and its leaders wanted EvCC to participate in its entrance ceremony each year.

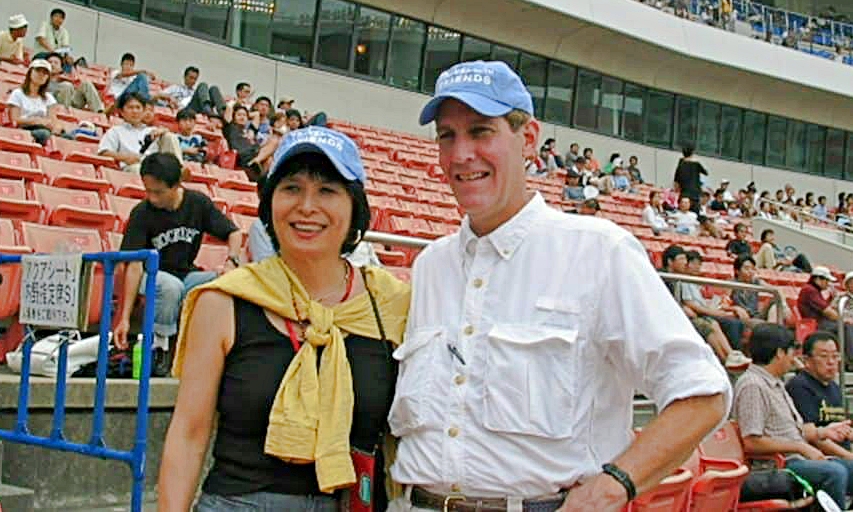

“These folks would invite two members of the board to go along, kind of as window dressing,” he said with a laugh. “I thought it was really cool, so I eventually suggested to Mayumi that we include members of the community so they could also talk with potential students and their parents. We called it the Travel With Friends tour, and, with that, we gradually learned something about how to do tours.”

The Bavasis decided to sell the Everett ballclub in 1999, and Bob left the board of trustees a year or so later, leaving him with an eye out for what was next. Next, it turned out, was developing the tours into what became JapanBall.

“I’d already picked up some interesting ideas that we’d implemented at the [Everett] club, so Mayumi and I decided to invite a group of minor league team operators to Japan [in 1999] to talk with clubs there and brainstorm ideas,” Bavasi said. “That worked well, but there is a limited number of MiLB operators, so we decided to go for fans.”

For Smith, a native of Hiroshima, it was a chance to visit friends and family, as well as a way to help build bridges between cultures.

“My mission for doing these tours is for cultural exchange,” she said. “I’d participated in a research project in which we interviewed atomic bomb victims, and the so many sad stories I heard created a very strong memory for me. It got me to wondering what I could do to help people learn more about each other as a way of promoting peace.

“My father was a naval officer in World War II and fought against the U.S.,” she continued, “but I’m married to an American, and we have two children and seven grandkids. Baseball is one way of connecting people, and Japan and the U.S. certainly have a strong baseball relationship.”

As Bavasi said, “It’s totally unusual for two cultures to come together over something that both think they own.”

For Bavasi, running a tour was a matter of remaining connected with baseball. “Plus, I just really liked going to Japan and wondered how I could work it so that I could go once a year,” he said.

This being before the internet was ubiquitous, he put a small ad in Baseball Weekly (now Sports Weekly) for a trip in 2000. He and Smith had no idea what the response would be or how the trip would pan out, but Bavasi said they got “six or eight” people to go and “didn’t make much money but enough to make it worthwhile.”

Enough to give it another go in 2001 when eight people, including some previous guests, participated.

“I was surprised by that,” Bavasi said. “I had thought it would be a one-time thing, but we found over time that about a third of the people had traveled with us previously. And it just kind of grew from there.”

At first, Smith wasn’t sure of the long-term prospects “because sometimes we got less than 10 people and didn’t make a profit, but it enabled us to go to Japan and fulfilled my personal and professional mission. Luckily, we had many Japanese friends who helped, as well as Americans like Michael Westbay [who handles ticketing for JapanBall tours], Marty Kuehnert [the first American general manager in the Japanese leagues], and [the late] Wayne Graczyk [a sportswriter for the Japan Times].”

There were many learning experiences. The two had picked up some ideas by bringing community members on the college-related trips, but there was still a lot to learn, much to do, and a vast amount of details to address. There were even opportunities to discuss differences of opinion regarding the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki near the end of World War II.

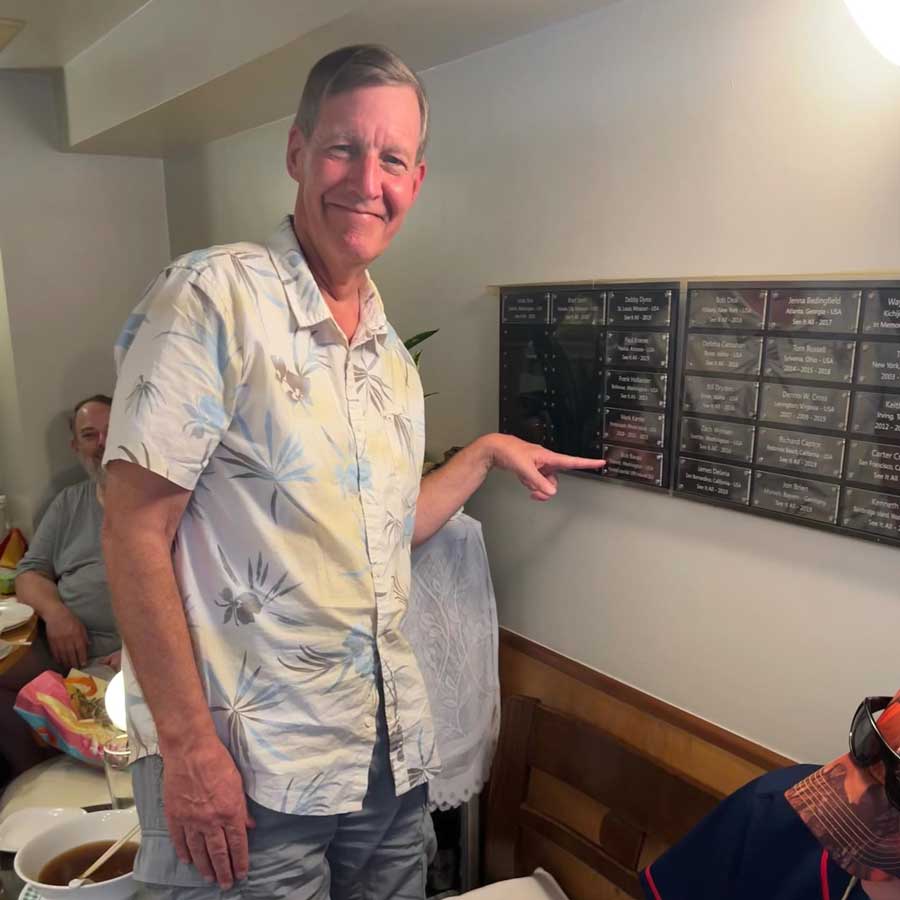

“I’m grateful to Bob for starting JapanBall. We benefitted each other because we had different backgrounds and ways of thinking,” Smith said. “I clearly remember being in the noodle shop, Café Roje, where the JapanBall Hall of Fame is now, and were discussing the bombing when the owner, Jun, jumped in and joined the conversation,” Smith said.

In a 2012 documentary, “Much More Than A Game: Japanese Baseball,” Jun, who owns the shop with his wife Koko, said, “By meeting with Bob, we started talking about the atomic bomb, and I saw that the American view and the Japanese view were quite different. We discussed whether it was right or wrong. And that’s how I got to know him. This was the kind of conversation we had when we first met. Now, they come every year.”

Along the way, of course, there were the inevitable happenstances.

Once, when the group was at a train station, and Smith was purchasing tickets, a guest went shopping for a suitcase without telling anyone. The group waited a half-hour for him and, when he didn’t return, went back to the hotel. “The guy was surely mad at me,” Smith recalls.

People often left items at hotels – one person left a partial denture – and on the trains, and Bavasi or Smith would have to try to retrieve them. One man left his entire insulin package on the train, and Smith had to go to the drugstore to find the items he needed. People sometimes got sick and needed to find clinics. On one occasion, Smith took an older man who couldn’t walk fast to the train station separately. Another time, when a group had several fast walkers and others who were slower, she recruited people on the train to take the faster people to the game while she took care of the slower group.

Smith even once delayed a bullet train — yes, those famous for not deviating even seconds from their precise schedules.

“We were going to Odawara, about 40 minutes from Tokyo, and not everyone in our group was in the same car,” she recalled, “so I went to each of our guests 10 minutes before arrival to make sure they were ready. But one person didn’t get off the train, so I went to check and found him sleeping. The Shinkansen doesn’t stop long, especially at a small station like Odawara, so I straddled between the platform and the train door so the guest could get out with his luggage.

“The conductor was really mad, and I was ashamed to delay the train’s departure. At the same time, I was proud of myself because the next stop would have been in Nagoya, two hours away. So I didn’t lose the guy, but I was mad at him because I’d given him the warning to be ready. Someone told me I should have just let him stay on the train, but I couldn’t do it.”

Which didn’t surprise Bavasi at all.

“People loved Mayumi,” he said. “She really made this thing ‘Japanese.’ She lent a lot to the whole operation. I’d say, for example, ‘Do you think we could get into the press box at the Tokyo Dome?’ and it would happen. There was no hill she couldn’t climb.”

And that continued, though the operation was usually limited to one trip per year in September, which worked well with Smith’s schedule at the community college and with Bavasi’s approach.

“There were a few times that we ran two trips a year, but that made it feel more like a job,” he said. “I could see the possibilities if I’d really wanted to run [JapanBall] as a business, but I just didn’t want to. I wasn’t in it for the money.”

Given that, he began thinking about exiting.

“I always liked the trips, and the people were the greatest,” Bavasi said. “But as I was getting older, I thought I should hand it off to someone.”

That someone turned out to be current owner and president Shane Barclay, who had been working for Major League Baseball’s Office of the Commissioner in the International Baseball Operations department with Bob’s brother Bill. Barclay was looking for a different avenue and was interested in baseball tourism. Bill put him in touch with Bob, and things developed from there.

“I asked Bob if he’d teach me about the tourism industry,” Barclay said, “and I went on the 2018 tour to learn by doing. Pretty soon after that, he asked me to lead the 2019 opening-day tour – Ichiro’s farewell – and after that, we began talking more seriously about me taking over. JapanBall was begging to grow, but Bob was wanting to do other things.”

The official handover was at the beginning of 2020. Though the COVID-19 pandemic shut down tourism for a good while, Barclay has since expanded the JapanBall portfolio with tours to the Dominican Republic, South Korea, Europe, and Alaska, amongst other destinations.

Bavasi remains a consultant, and he also subbed for Barclay on the 2023 tour while the latter stayed home to help care for his newborn son.

“It was fun to get back in the saddle,” Bavasi said.

As he once remarked while pointing to the Tokyo Dome in the background, “You can see all the temples and other things that you want, but, to me, if you ever want to see the culture of Japan, you can see it right here.”