If you search “Japanese baseball” on Amazon.com, the very first item that appears for purchase is a paperback copy of You Gotta Have Wa, by Robert Whiting. Called “the definitive book on Japanese baseball” by the San Francisco Chronicle, “Wa” represents an introduction into the Japanese version of baseball, showing baseball fans around the world a new way to see their favorite sport, and revealing an aspect of Japanese culture often unseen on television and movies.

When I first joined the JapanBall team, I immediately picked up a copy, hoping to understand a little more about the fascinating new frontier I was taking on. I enjoyed the book in general, especially learning about the work ethic of the players and the ōendan (official team cheering sections), but found the hard contrast between American ballplayers’ style and the wa (“harmony”) team culture uncomfortable, and difficult to understand.

What’s more, evidence of the cultures meshing over recent years – both thanks to what Whiting calls the “Nomo Effect” in Major League Baseball and the efforts of NPB import players like single-season hit king Matt Murton and import managers like Bobby Valentine and Trey Hillman – makes You Gotta Have Wa seem a bit outdated at times, with its conflicts overshadowing the fantastic baseball being played in Japan and the tremendous efforts made by both player and team to create optimal results.

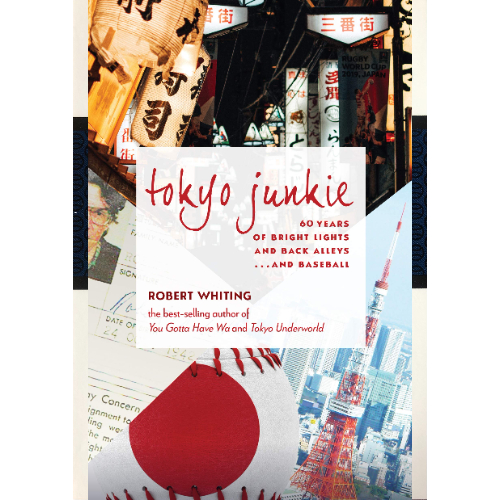

As a result, when I was tabbed to read and review Whiting’s latest book Tokyo Junkie, I remembered our conversation, and was prepared to read with a lens of scrutiny. As is usual with Whiting’s writing, however, that lens ended up being removed early in the book, as I became engulfed in his wonderful storytelling and recollections.

Tokyo Junkie – a memoir of Whiting’s time in Japan – is not only a fantastic introspection on the author’s own life and library, but one of the most complete overviews of Tokyo’s constant evolution as a city. Whiting, who arrived in 1962 as part of the United States Air Force, manages to break down the modern history of the world’s most modern city, a complicated, twisting path that includes crime bosses, corruption and disasters, into just 369 pages.

The book gives readers a complete lesson on the history of modern Tokyo, beginning right at the event that marked its beginning: the 1964 Summer Olympics. Before the Olympics, construction raged day and night throughout the city, giving the impression that Tokyo had made years of advancement seemingly overnight. The construction never ends in Whiting’s tale, as the buildings rocket upwards and houses are rebuilt overnight, keeping thousands of people employed and – as Whiting explains in an aside to the reader – keeps the Yakuza machine running.

This is all explained within the first 80 pages, or the first five years of Whiting’s time in Japan. That’s how thorough the book is with history, and yet it never drags, largely in part due to Whiting’s writing style. The book jumps from “The Greatest Olympics Ever” to samurai movies to the first drafts of “Wa” to dealings with the Yakuza, all while Whiting sprinkles in fascinating facts and anecdotes relevant to each.

The star of the show, despite it being an autobiography of sorts, is the namesake city, told through the characters Whiting introduces, including: the eccentric plastic surgeon Dr. Sato, who gave him his first experience of Japanese high society; gangster-turned-restaurant-proprietor Nicola Zappetti, whose experience with the mob gave Whiting material for his book Tokyo Underground; and famed media guru Tsuneo Watanabe, who helped shape Whiting’s experiences with the media and later became an enemy due to open criticism of the Yomiuri Giants.

Also featured are baseball players galore (Reggie Smith, Hideo Nomo, Ichiro Suzuki to name a few), commissioner of Nippon Professional Baseball Takezo Shimoda, Yakuza enforcers who became Whiting’s close drinking friends, arguably one of the greatest wrestlers in Japanese history “Giant Baba,” and countless politicians and historical figures that pass through Whiting’s story, not as featured players, but as an ensemble. Their role does not take away from the story Whiting tells, but builds upon it, offering a view of just where Whiting is in his life… along with the city that grows behind it.

With all the important figures and topics being thrown around, Whiting’s ability to engage with the audience on a personal level shines throughout the book, as he connects readers with his own feelings and logic that takes him from story to story. Despite being a Pulitzer-prize finalist and New York Times bestselling author, Whiting never writes himself as a champion, but almost as a sitcom character in wacky situations.

Why did he first get involved with baseball? Because that was one of the only topics he knew about in the country, and helped him get acquainted with his friends and neighbors. Why did he end up in the NPB commissioner’s office, currying favor by offering a bottle of Johnny Walker Red Label whiskey? Because it was a last-ditch effort to help legendary baseball writer David Halberstam get media access to the Yomiuri Giants, a team which Halberstam had described as more difficult to deal with than the White House. How did he end up becoming friends with one of the best wrestlers in the country? He lived under his apartment and often felt plaster rain down on him as the champion practiced his dives. All normal, everyday situations that could have happened to anyone with enough grit and courage to try.

That is the greatest strength of Tokyo Junkie in my opinion. Whiting’s ability to speak from the heart about the experiences he has, and explain his observations of a city that never stops growing; not as a central figure who made the world stop with his work, but as a fly on the wall, watching people come and go and falling in love with the environment in the process. What’s more, even when he chooses to wax poetic about the things that did made him stay all those years, his explanation is simple:

“Above all, it was baseball that gave me the window I needed into the workings of the culture,” he writes near the book’s conclusion. “Researching and writing… You Gotta Have Wa helped me organize my thinking about my adoptive home and crystalize my understanding of the cultural differences between Japan and America… which helped open my mind and expand my horizons in ways I never could have imagined.”

Opening minds, expanding horizons, baseball. Seems like JapanBall and Whiting go hand-in-hand.

Note: JapanBall receives a small commission if you purchase the book using the provided link.