Although it’s a powerful mainstay in the current landscape of sports, Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB) had rocky beginnings. Despite baseball being a popular school and university sport since the late 1800s, the first Japanese Professional Baseball League was not established until 1936. Earlier attempts at forming professional teams in Japan occurred with the Nihon Undo Kyokai club in 1920 (renamed the Takarazuka Kyokai in 1922), and the Osaka Mainichi in 1925, but neither of those efforts had the momentum to form a league.

The third effort at professional baseball in Japan occurred in 1934. This team, formed of some of the greatest high school and collegiate players in the country, was first arranged to take on Major League Baseball (MLB) All-Stars Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and others in their legendary 1934 barnstorming tour of the country. The tour is known today as the event that really initiated popular interest to form a professional baseball league, and the All-Stars’ role in stirring that interest has been noted by many baseball historians.

Less well-known, however, is the role of Negro League All-Stars in the development of the game. Black ballplayers marked several milestones in the early days of Japanese baseball, including the first professional home run hit in Meiji Jingu Stadium, the farthest ball hit at Koshien Stadium, and even the first African American player to break the color barrier in 1936 — 11 years before Jackie Robinson. Yet these achievements, like many stories of the Negro Leagues, received less and less attention with the passage of time; they were overshadowed by MLB’s might.

“I think it’s important to recognize them for their role and helping to build the bridge between the US and Japan,” baseball historian Bill Staples Jr. said in an interview. “A lot of credit is given to the white tours of major leaguers, but very little attention or even credit is given to the not just the African Americans, but I’d say other historically marginalized groups as well, like Japanese Americans… I think both of them played really important roles, and just like in society, they’re kind of pushed to the side and not given the attention and the spotlight that they deserve.”

Now, in an effort to help honor the hidden legacy of Black ballplayers in Japan, we will share these stories with a greater audience. With help from historians like Bill Staples, Jr, and Ralph M. Pearce, we’ll attempt to establish a timeline for the Negro Leagues’ role in Japanese baseball, highlight different key players and their achievements, and reflect on the influence they had on the game overall.

Get ready for a new side of history.

The Royal Giants’ Barnstorming Tours

To fully tell the story of Black ballplayers in Japan, it’s critical to first highlight the Negro Leagues’ creation, as well as the different key teams and players within it.

Although African Americans had been playing on informal teams and leagues since the 1870s, 1920 has been recognized as the “official” starting point for organized, professional baseball in the Negro Leagues. On February 13, 1920, former pitcher Andrew “Rube” Foster met with the owners of eight independent teams with the intention of creating a new league: the Negro National League. Following this meeting, different teams and leagues were formed as alternatives to the midwestern National League, including the Eastern Colored League and the California Winter League.

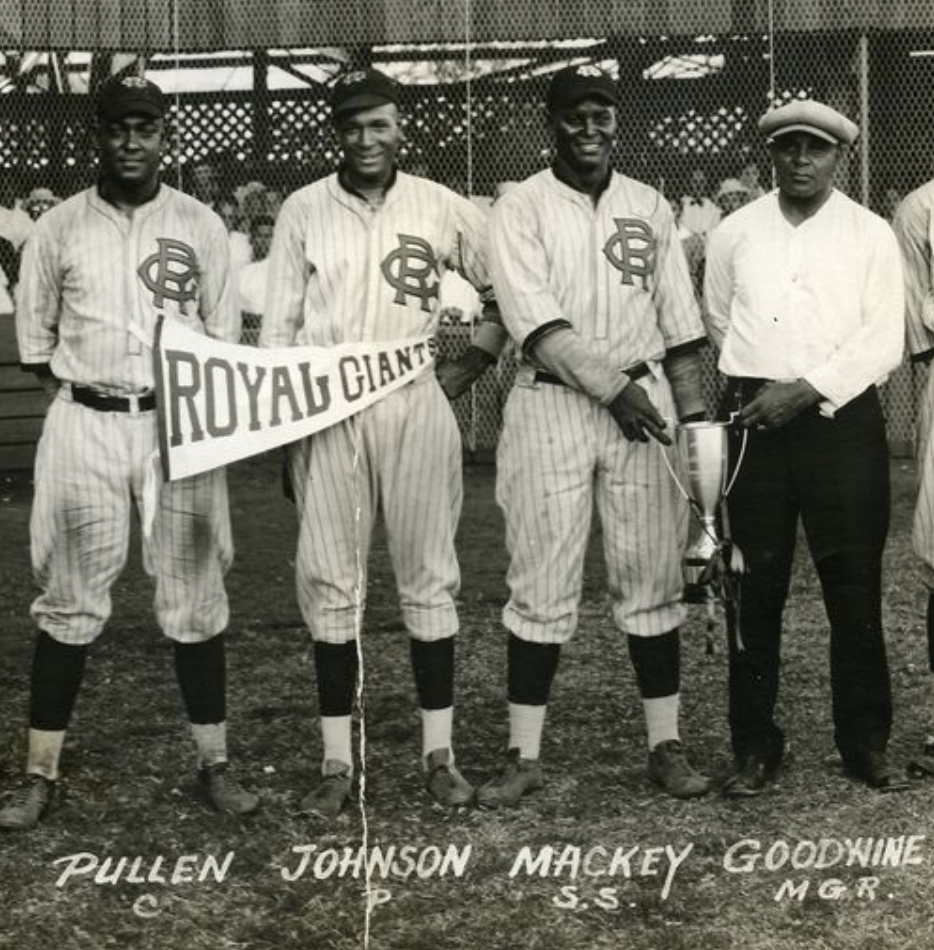

Over time, different Black players began to gain attention for their skill and prowess. Raleigh “Biz” Mackey of the Hilldale Daisies in the Eastern League was known for his mighty bat. Herbert “Rap” Dixon of the Harrisburg Giants in the National League was a fantastic contact hitter, and a stellar fielder to boot. Over in California, manager Lon Goodwin had established a reputation as a veteran manager with the Los Angeles White Sox, a ballclub he founded in the early 1910s.

Also in California was Kenichi Zenimura, a Japanese-American baseball player and international promoter. In the 1920s, Zenimura played and managed the Fresno Athletic Club, a team of Japanese Americans playing semi-professionally. When the team won the Japanese American Championship in 1923, they were invited to play in Japan in exhibition games the following year, introducing to Zenimura the fascinating (and profitable) touring experience, and planting the seeds for the creation of more overseas opportunities in the future.

In 1926, Zenimura and Goodwin arranged a two-game series on the 4th of July-weekend at Fresno, bringing out all the stops to promote the game for both the Black and Japanese audiences. Fresno won both games, but Zenimura was impressed with the potential of the White Sox, and encouraged Goodwin’s team to tour Japan to promote the game.

“African Americans and Japanese Americans were in the same class situation in California, so they had a lot of social interaction,” Staples said. “Zenimura has a history of playing African American teams, going back to the early 20s… it’s during that incubation period, where they have that weekend match against Lon Goodwin’s L.A. White Sox… they’re there for the entire weekend in Fresno, and the conversation just picks up about Japan and why perhaps they should go. So after that weekend, Zenimura, historians believe, got the wheels in motion, because the ‘Los Angeles White Sox’ are specifically invited in December 1926 [instead of] any other team. So that’s the strong Zenimura connection there.”

Goodwin accepted the invitation but didn’t take the White Sox. For a tour of this magnitude, he wanted to show the audience the best of what the Negro Leagues had to offer – an All-Star team of his own. He invited Mackey to join the squad, along with a few other well-known names like Rap Dixon, and leveraged the name of his California Winter League team, the Philadelphia Royal Giants – a name that is perhaps inspired from the Rube Foster’s Philadelphia Giants, a club that dominated headlines in the 1900s as the best Black baseball team.

“They were kind of the stronger brand of his two teams,” Staples said. “His intent after the invitation was to take most of the Negro League stars…but he couldn’t get all those players to jump their contracts for the ‘27 season, so it was a blend of talent. It was the Hall of Famers, the major leaguers, and then the semi-pro players in California to fill in the gaps.”

Staples also noted that Goodwin’s intent was not to bring players with just name recognition. “I don’t think the marquee names were that important, but I think he wanted to bring the strongest team possible,” Staples said. “These guys want to make money… I think it was just a matter of who wanted to pursue the financial opportunity, and maybe the adventure of travel.”

The Royal Giants arrived in Japan on March 30, 1927, to far less attention than Babe Ruth would receive seven years later. While Ruth’s team received much media attention and paparazzi, the Royal Giants received just a few write-ups in local sports pages. Not to be discouraged, however, the team would play their first game the next day, winning against the Mita Club from Keio University, 2-0. According to local sources, many were impressed with the team’s athletic ability and stellar defense, and noted that the games were very fun to watch.

Some key examples of the team’s athletic ability are now historical snapshots in Japanese baseball history. On April 6 at Koshien Stadium, Dixon smacked a long ball deep into the gap in left-center field that bounced off the wall and rolled back towards the infield. At 420 feet, it was the longest ball ever hit in the stadium and the accomplishment was commemorated with the spot on the wall where the ball hit being painted white. On April 20, Mackey clobbered a ball 417 feet over the centerfield wall at Meiji Jingu Stadium– the first over-the-fence home run in the new stadium. He would then hit two more, on April 25 and 28. The Negro League All-Stars were showing off power that Japan had never seen before.

While the Royal Giants were skilled and strong, they were intent on keeping the games close with the local Japanese teams. Although the team went 23-0-1 over their tour, many of the games were incredibly close, with the Giants only winning some by a run or two. Even in tough games like the one tie game they experienced, against Daimai Baseball Club, they were patient with their opponents and umpires, didn’t argue calls, and just tried to enjoy the games. Many of the Japanese players who competed against the Black ballplayers noted that it was a wonderful experience, saying that the chance to play against professional-caliber players and compete with them was a true joy.

“I think they caught on early on that the Japanese players were still developing,” Staples said. “So there was that level of respect and desire to keep the games dignified… they respected their hosts, they honored the customs. They just treated everybody with respect, and I think that carried over onto the ballfield, as is reflected in their interactions with opposing players, umpires, and the fans.”

The tour was also important in the context of the other, more popular U.S. tour. While Babe Ruth’s team attracted a lot of fan attention and spectators, the games themselves were humiliating for the Japanese squads, as most of them were routs and the American team neglected to take the games seriously. The Royal Giants, as Kazuo Sayama wrote in “Gentle Black Giants,” acted as “shock absorbers” for the Japanese teams, encouraging them that they did have the potential to develop the skills to compete at a higher level.

Manager Lon Goodwin also expressed this sentiment, writing in 1927 that he thought “there is not any other country where we could play and enjoy games while not paying any attention to wins or losses. We especially admire the passionate baseball fans, who are well educated and watched the games with respectful manners. That left us with a great impression of Japanese baseball… We wish great success and a promising future to Japanese baseball society.”

Goodwin would return with the Royal Giants to Japan in the winters of 1931-32 and 1933-34, with more Negro League stars wowing the crowd. Lost among the pages of the MLB All-Stars tours, the Royal Giants were critical elements of the early days of Japanese baseball; so much so that when professional baseball was developed a few years later, teams continued to look to America for stars.

One of those stars was Jimmy Bonner, who would become the first player to break the Professional Baseball Color Barrier in 1936.

Jimmy Bonner: the First Black Player in Japan

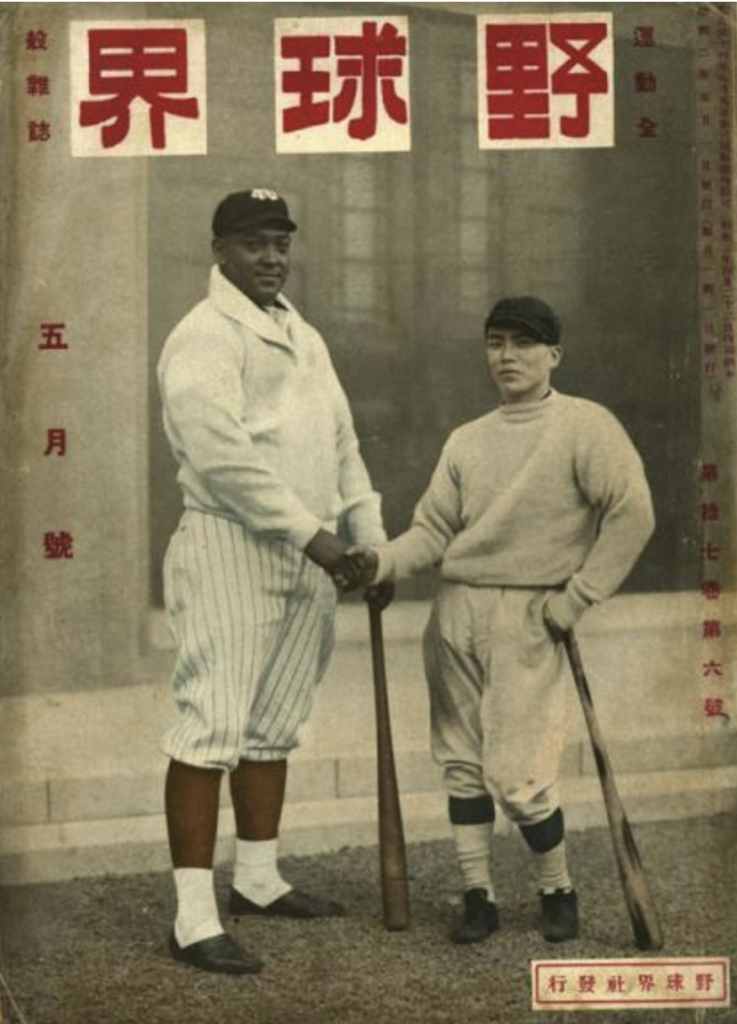

Following Babe Ruth’s 1934 barnstorming tour, the members of the Japanese All-Star team stuck together and would eventually become Japan’s first professional team: the Great Japan Tokyo Baseball Club, or as it’s known today, the Yomiuri Giants. In 1936, several teams were organized to challenge the Giants, resulting in the Japanese Professional Baseball League (JPBL); with that, professional baseball was officially underway in Japan.

In order to fill out their rosters, however, many teams looked to the United States to provide the talent. Fumito Horio, a Japanese-American, played for the Yomiuri Giants on their tours of the States, becoming the first American to play professionally in Japan. Harris McGalliard (known as Bucky Harris in Japan) would follow him, and would actually win the JPBL MVP award in the fall of 1937. Between those names, however, was a third: James “Jimmy” Bonner, a Black pitcher who was known for his fearful submarine delivery and his prodigious approach at the plate.

Born in Louisiana in 1906, Bonner played baseball since he was in junior high, often splitting time between his regular job as a tailor and playing in the less-organized leagues; he played for the Shreveport Black Sports, which went through three league changes and their ballpark being burnt down in the early thirties.

Looking for a new opportunity, Bonner left for West Oakland in 1932 and began playing for the San Francisco Colored Giants. Bonner, who had previously only worked as a position player, began working on his pitching. He garnered local headlines on July 8, 1934, when he struck out sixteen and threw a no-hitter. He was also gaining attention for his skill with the bat, quickly becoming a double-threat.

“The headlines in the news really point to him as a standout,” baseball historian Ralph Pearce said. “I get the impression he was a fairly new pitcher… Certainly had a lot of strength at the plate, so it doesn’t sound to me like someone who had been focusing up to that point, really on pitching. And so it appears he definitely had potential and talent there.”

Bonner then played for the Oakland Black Sox in 1935 and the Berkeley Grays in 1936, the latter of which gained him much success. Playing in the Berkeley International League, Bonner set a new record for single-game strikeouts (17) and helped the Grays win a share of the League Championship. He then played for the Berkeley All-Star team in a California State Tournament and helped the Civilian Conservation Corps San Pablo Dam team win the championship by pitching three complete games in two days.

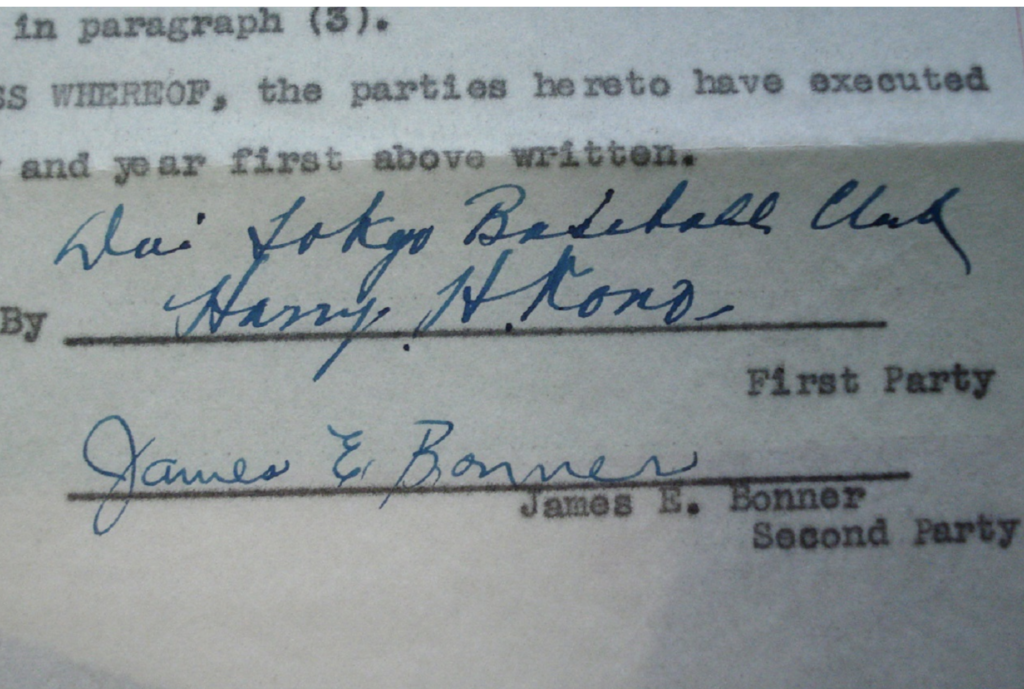

Overworked? Maybe, but he was gaining local attention from multiple communities, including the Japanese-American community. Harry H. Kono, a local businessman and agent for the Dai Tokyo Baseball Club (later the Shochiku Robins), noticed his work and invited him to sign with Dai Tokyo.

“I think that Kono was respected, and given [his] role as a scout… reconfirms the important role that Japanese-Americans play because they understand the language and the customs of both countries,” Staples said. “So they play an important role behind the scenes in negotiating contracts and organizing chores. To me, that’s one of the more important stories of Jimmy Bonner.”

Bonner agreed for a hefty price: 400 yen a month (equivalent to $200 a month in the States at that time, and over $3800 in today’s money) and a steak breakfast every day. For context, the annual salary of a Yomiuri player was 140 yen a month; the legendary Eiji Sawamura was making 170 yen a month, and his American counterpart, Harris McGalliard, was making 300 yen a month. It was a risk Dai Tokyo was willing to take, however; winless through the first half of their season, they wanted to try to turn the season around at all costs.

“They were looking for a savior there,” Pearce said. “They were looking for someone who was going to pull them out of the cellar.”

Bonner arrived via steamship to Japan on October 5, and appeared in his first games two weeks later against Nagoya Baseball Club, playing first base in two exhibition matches: a 13-3 loss, and a 5-4 win. The Japanese newspapers began to write of Bonner’s skill, telling readers of his “viciously fast and powerful submarine pitch.” On October 23, Bonner went up against the legendary Henry “Bozo” Wakabayashi and the Hanshin Tigers for his first real test; Bonner boasted to Wakabayashi before the game that he would shut them out.

Unfortunately, Bonner’s talk was met with lots of walks: in the first inning, he walked two batters, loaded the bases, and allowed a grand slam. He’d pitch until the seventh inning but was replaced after he experienced more control issues. Although Dai Tokyo would come back and tie the game (including a key RBI from Bonner), many were disappointed with Bonner’s performance. He started again the next day, but after he issued six balls to the first two batters, he was moved to second base. Dai Tokyo lost 7-4.

A week later on November 3, Bonner would get another shot, playing against the Tokyo Senators, but gave up three straight walks in the second inning and was pulled in the 13-9 loss. Dai Tokyo played the Yomiuri Giants and legendary pitcher Victor Starfin the next day, with Bonner playing second base. While he whacked a hit and helped Dai Tokyo notch a 3-0 lead, he had a crucial error in the ninth that allowed the Giants to come back and win.

He played a few more games at first base and as a pinch hitter, including a memorable occasion where a group of kids held up a sign that said “Bonna-chan!” in his honor (“chan” is a Japanese term of endearment), but only survived to the end of the pay period. At the end of the month, Dai Tokyo reported that “he wasn’t feeling well, so we sent him home.” In four games, Bonner had gone 0-1 and notched a 9.90 ERA over 9.2 innings, while walking 26.9 percent of his batters. He had also batted a stellar .458 average, but it wasn’t enough to make up for his poor pitching performance in key games.

“They could see Jimmy had talent, but that wasn’t the talent that they were looking for,” Pearce said. “He was good at the plate, which was great, he was okay at fielding… but what they were really after was a pitcher that could help them, and it just didn’t work. You could argue that he didn’t have enough time and that he needed some adjustment… he needed some of his own development, but I think that for Dai Tokyo, they just didn’t perhaps have that faith in him, or the ability to make that investment.”

Historians have noted several key factors in Bonner’s failure to adjust: one was a smaller strike zone, with the average Japanese player standing at just 5-foot-4 with a fantastic training in patience at the plate. Others noted that the ball was likely very slick for his liking and that the quick turnaround to a whole new game would be hard for any player.

Bonner, however, deserves recognition for his achievement: he was the first Black player to play professional baseball outside of the American Negro Leagues, eleven years before Jackie Robinson. What’s more, his trailblazing path was nothing in comparison to his astounding personality and confidence in himself, skills that would help carry him through this footnote in history and beyond:

“I think what makes him an amazing person too is… here’s this not well-off African American young man in the early days of the depression,” Pearce said on Bonner’s legacy. “He comes out here [to California]… he brings his wife out here to California and [doing] whatever he’s doing to get along, and then he’s playing baseball, and then he gets involved in this thing to go over to play in Japan, and he just seemed very confident… he even negotiates steak for breakfast every day. Even when he was failing, he still seemed confident, he still believed in his ability, and even though it didn’t pan out, he gave it his all right up to the end. He was playing it for what it was worth, so he’s just an amazing person, just in terms of his personality and his character.”

Although Bonner may not be known for more than this historic path, his play in Japan set a precedent for future generations to come, and perhaps further players down the line; Black ballplayers like Jimmie Newberry, John Britton, and the legendary Don Newcombe and Larry Doby.

But that’s a story for another time.

Stay tuned for Part Two of this story! For more information about Black ballplayers, check out “Gentle Black Giants” by Staples Jr. and Ralph Pearce’s books. To stay informed of when Part Two is published, subscribe to our newsletter below.