In 2020, several celebrations were held to commemorate the centennial of the Negro Leagues. Until Jackie Robinson made his debut as the first Black Major League Baseball player for the Brooklyn Dodgers, the Negro Leagues were the highest level of talent for Black baseball players, and featured some of the greatest talents ever seen in baseball, including Josh Gibson, Larry Doby, Satchel Paige and even Robinson himself.

Other names, however, have been lost to time, as the players often played in MLB’s shadow; the teams were just a necessary alternative, a product of the unfair time. MLB was a giant, and their All-Stars made international headlines for their power and skill. One of the most commonly cited examples is the 1934 MLB All-Stars’ tour of Japan, in which players like Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig tore through the country’s college teams en route to a perfect record.

Yet in 1927, seven years before Gehrig and Ruth stormed the country, another American baseball team took to Japan: the Philadelphia Royal Giants. Made up of several Negro League All-Stars, the team was a critical part in not only developing interest in baseball in Japan, but also boosting the confidence of young Japanese players, laying the foundation for Japan’s own professional league.

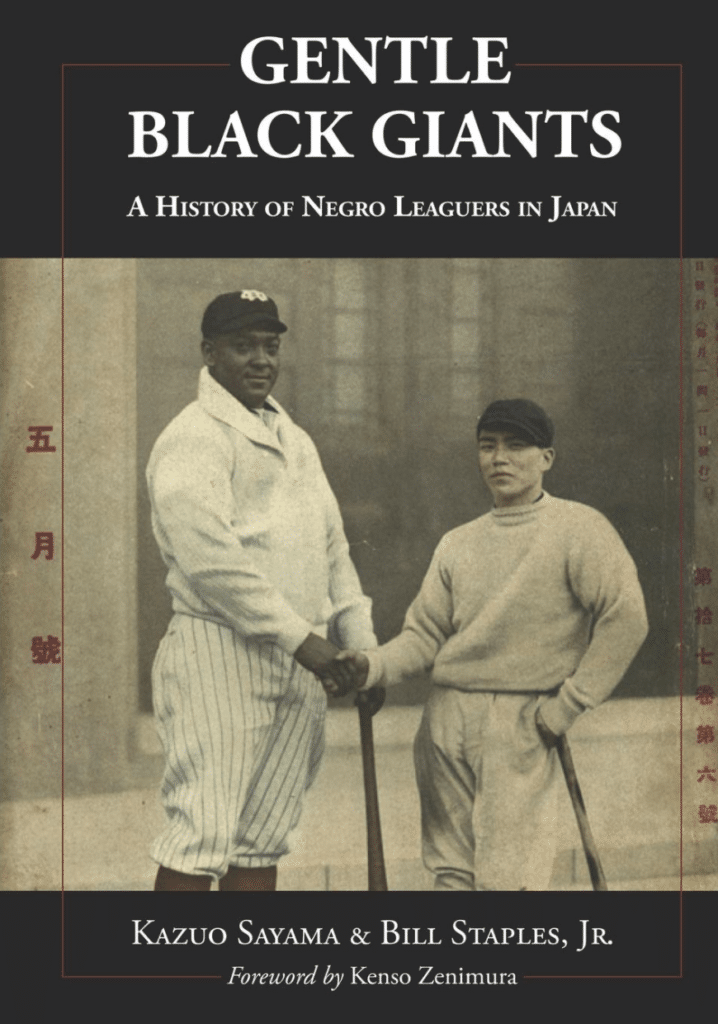

The tour, along with two others that followed, is the subject of “Gentle Black Giants,” a book and historical portfolio written by Japanese baseball historian Kazuo Sayama and translated and re-written by Bill Staples, Jr. The book is a fantastic collection of factoids and trivia points for any Japanese baseball fan. For example: did you know that the first home run hit at Meiji Jingu Stadium was hit by a Royal Giant, Biz Mackey, nine days before the “official” record was set? Or that one of the farthest balls ever hit at the original Koshien Stadium was by Royal Giant Herbert “Rap” Dixon, a line drive that smacked off the outfield wall? Or, for that matter, did you know that Jingu Stadium was built for collegiate competition and Koshien Stadium for high school competition, both of them pre-dating professional baseball in Japan?

In his work, Sayama attempts to recreate these highlights lost to time, along with the games and crowd reactions. This herculean effort is not lost on the reader, and any baseball fan will appreciate the number of statistics included to support his findings, along with his interviews with past players and historians. In addition to his narrative of finding these stats, the book also provides ample material for the baseball historian in all of us, including profiles of players like Jimmy Bonner (who broke the baseball color barrier in Japan in 1936, 11 years before Robinson debuted with the Brooklyn Dodgers), photos of the players, and numerous scorecards.

In addition, Sayama not only provides evidence on the tour and games, but argues what their impact was on the Japanese game, claiming that the Black athletes’ performance was fantastic, but even more important was their patient demeanor. Despite bad calls from umpires or even poor scorekeeping decisions that may have cost them a game (their only recorded loss in the books), the Black players never spoke out or fought back, simply smiling and enjoying the game with their opponents. Sayama contrasts this with Babe Ruth’s tour in 1934, saying that while the Royal Giants took pitches with a grin, the MLB All-Stars played the games their way and forced the umpires to make calls for them. The Royal Giants’ tours, Sayama writes, were “shock absorbers” for the Japanese players, as they helped not only boost fondness for the game in the country, but also gave them confidence in their own abilities because the Royal Giants made an effort to make the games competitive, as opposed to embarrassing their less-talented hosts as the MLB All-Stars often did.

In his work, Sayama aims to not only educate his audience on the games themselves- which were a lot more competitive than Ruth’s games, with many scores only being a few runs apart- but also on the players who dazzled in front of the Japanese audiences; an achievement, I’d argue, that should earn Sayama praise. The team, which included the aforementioned Mackey and Dixon, was an All-Star squad that never got their recognition in the States. Mackey was a fantastic catcher and player, but until he was finally inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006, his most famous role was mentoring the up-and-coming young stars who would help break the MLB color barrier – stars like Larry Doby and Roy Campanella. Not long before Mackey’s death, Campanella invited Mackey to “Roy Campanella Day” and paid tribute to his former mentor in front of nearly 100,000 fans. Also included in the book is a tear-jerking profile of Mackey, in which he laments to a reporter “I was born 30 years too soon.”

In this book, Sayama and Staples not only detail games played in Japan by this squad of All-Stars, but re-insert their names into the history of international baseball. Mackey. Dixon. Slugger Frank Duncan, who mentored Jackie Robinson. No longer just faces in photos, Sayama and Staples give them historical profiles and tell their stories for a new audience, telling their readers that they were a critical reason why baseball was able to progress in both Japan and the United States.

As such, I whole-heartedly recommend this book on multiple fronts: in celebration of the Negro Leagues’ centennial, for all baseball history buffs who want more information on a great game and team, and for anyone just looking for historical material and new stories to learn. This book is a “home run” in my opinion, and I highly recommend checking it out.

Note: JapanBall receives a small commission if you purchase the book using this provided link.