One of the most interesting roles in Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB) is the role of the kantoku, or manager. Despite the almost authoritarian role of the manager and his outsized influence on the club’s culture – a product of the importance of seniority and hierarchy in Japanese society – teams usually hire internally, choosing former players who had served the club well on the diamond rather than outsiders who may be able to provide a unique perspective in the dugout. While it may be seen as an act of loyalty to their former star, executives have admitted that attendance numbers play a significant role in having a former superstar as manager. This isn’t to say, however, that the gamble doesn’t often work; plenty of former MVPs have managed their teams to great success, including Sadaharu Oh, Shigeo Nagashima, and Katsuya Nomura.

There remains a critical question to be asked: would there ever be a kantoku who could be considered as good a manager as he was a player? The answer is a no-brainer: Tetsuharu Kawakami, who recorded over 2,300 hits and was referred to as the “God of Hitting,” and managed the Yomiuri Giants to 11 Japan Series wins, including the “V9” years, in which his team won nine straight titles. from 1965 to 1973.

Not many recognize, however, that Kawakami’s career was not one of pure success, but one of struggle, coincidence, and conflict; both on and off the field. A man so well-regarded in Japanese baseball history, but who had to fight both himself and his critics to push himself – and his teams – to the top. In this comprehensive article on Kawakami’s career, all of the debates – as well as their resolutions – will be revealed, once and for all.

But to first get to the dugout, we’ll have to travel to the city of Hitoyoshi, on the banks of the Kuma River.

Early Life

Kawakami was born on March 23, 1920 in Hitoyoshi, Kumamoto. His early life saw many struggles. His father went bankrupt due to gambling, and when he was five, Kawakami slipped on a gravel road and severely injured his right arm. Due to the pain and slow progress he made in healing, he eventually learned to do everything from his left side… an event that would impact his success as a hitter greatly.

Upon entering Kumamoto Tech for high school, he immediately became a critical pitcher for their team and grew close with his catcher, Masaki Yoshihara– who would also eventually gain entry into the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame. Kawakami and his teammates enjoyed plenty of success, even making it to the final round of the Koshien national high school baseball championship tournament in 1937, but lost 3-1 in the final game. Following the tough loss, Kawakami made his first impact on the legacy of Japanese baseball when he scooped up a patch of the dirt from the hallowed infield to take home with him; though it’s disputed that he was the first to ever do so, he may have very well started a new tradition that’s still being practiced today.

Despite his success, professional scouts did not pursue Kawakami, and he did not think much of a career in baseball. The scouts were, however, fixated on Kawakami’s battery mate, Yoshihara. The Yomiuri Giants – who were still in their early days – were looking for their franchise catcher, and Yoshihara appeared to be their guy. Negotiating with the young catcher, however, revealed a critical clause: Yoshihara “would not join if Kawakami wouldn’t be with him.” One of the most influential men in the history of the Giants was ironically not the “main man” in his contract, but a “throw-in” to keep their new prospect happy, this being admitted by Kawakami himself on a few occasions. Even with the contract, Kawakami did not expect to play much, apart from the occasional pitching appearance.

Kawakami the Player

Fate, however, once again came through for Kawakami, as he was thrown a first baseman’s glove when the regular went down with an injury in 1938. It didn’t take long for Kawakami to shine in his new role, as he followed his rookie campaign with some of the best hitting the young Japanese Professional Baseball League (JPBL) had ever seen, leading the league in batting average in 1939 (.338) and 1941 (.310), and in home runs (9) in 1940.

Yet like many famous players of the era, Kawakami’s career paused when World War II broke out. He was drafted – along with Yoshihara – into the army and served from 1942 to 1945. Tragedy struck in 1944 when Yoshihara was killed in Burma. The two battery mates were separated for the final time.

Kawakami, who served until the end of the war, returned home to find Japan suffering a severe food shortage, and decided that a return to baseball was not the right choice. He returned to Kumamoto and harvested crops for his family.

The Giants, meanwhile, were looking to revive baseball’s success following the war and came knocking at the Kawakamis’ door before the 1946 season. Still concerned over the future and hoping to feed his family, Kawakami made an ultimatum: he would play for no less than 30,000 Japanese Yen; roughly $7500, in modern dollars. The Giants obliged, and Kawakami returned to Tokyo, where he became the nascent league’s first post-war superstar.

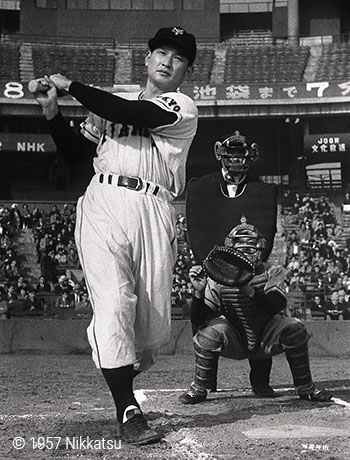

While other players remained shaken from the war effort, Kawakami seemed to pick up exactly where he left off. Sporting a red bat – which became a revered symbol of his career (and was often compared to the blue bat of his rival Hiroshi Ohshita of the Tokyu Flyers) – Kawakami aimed to “bring color” back to the war-devastated Japan, raise the morale after years of military conflict, and help Japan fall back in love with baseball once more.

Countless grueling hours of Zen-like practice allowed Kawakami to dominate the league for the next 13 seasons. Honing his craft into the darkest hours of the night, Kawakami claimed that the extra hours of practice allowed him to see “baseballs stop in the air” when facing opposing batters, an unbelievable sensation that only fed into the fans’ nickname for the slugger: the “God of Hitting.”

Kawakami won batting titles in 1953 (.347) and 1953 (.338), but his best year came in 1951 when he recorded a .377 batting average and struck out just six times over 424 plate appearances (his batting average stood as a league record until Randy Bass beat it in 1985). He would become the first player to reach 2,000 hits – finishing with 2,351 in his career – and only retired once his average dipped below .300 average for the first time in his final two seasons.

A left-handed-hitting savant with a career batting average of .313, American baseball fans could consider him the Japanese contemporary of Ted Williams, the Boston Red Sox’s “Splendid Splinter.” Both played almost identical years (Kawakami 1938 to 1958, Williams 1939 to 1960), missed time due to the war effort, were their league’s best batters, and eventually earned managerial gigs.

Kawakami’s managerial success began when the Giants officially hired him as manager in 1961, and the second part of one of the greatest careers in Japanese baseball was born.

Kawakami the Manager

When Kawakami took over as kantoku of the Giants, the Japanese game was in the middle of a professional revolution. Nine years after the first arrival of foreign players like John Britton and Jimmie Newberry, the impact of the American game was being seen across NPB. Expatriates were helping their teammates pick up a new perspective on the game. For example, players like Daryl Spencer – a former slugger of the San Francisco Giants and Los Angeles Dodgers – joined the Hankyu Braves in 1964, and helped his new teammates gain a mental edge by looking for tipped pitches while role guys like Don Blasingame – who played infield for the St. Louis Cardinals and Cincinnati Reds – served as a coach with the Nankai Hawks on the importance of mental strength, and how to gain a competitive edge mentally.

The Giants – as well as parent company Yomiuri – knew the power of the American game well, and helped further its incorporation with collaborations with MLB teams; in particular, the mighty Los Angeles Dodgers. Sportswriter Sotaro Suzuki observed the team when they were still in Brooklyn, and brought the idea of a Japanese tour to team owner Walter O’Malley, which came to fruition in 1956. The tour created a lasting impression on both teams, as the Dodgers would regularly invite Giants coaches and players back to the States to train with their squads in Vero Beach, Florida – a trip Kawakami would make many times.

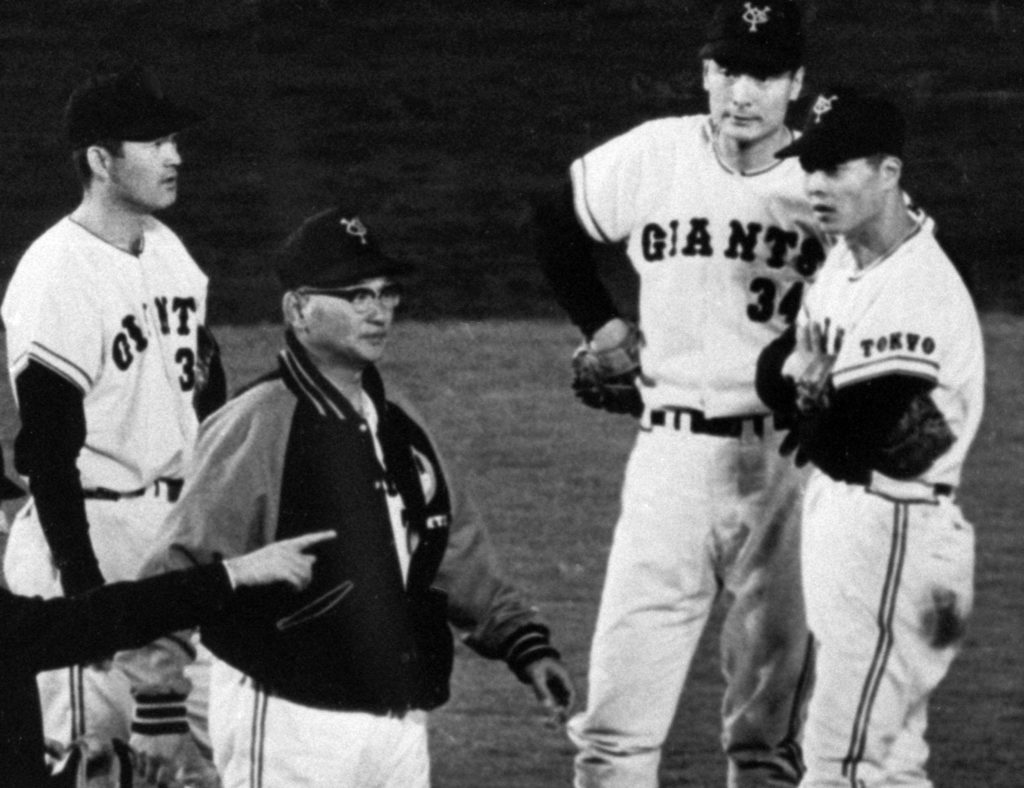

Inspired by the Dodgers, Kawakami took a new approach to managing: having no true superstar, yet contending year after year. Particularly taking note of Al Campanis’s “The Dodgers’ Way to Play Baseball,” Kawakami observed that above all else, having the right team culture was the way to win games. He implemented new tactics, positioning, and roles for both coaches and players. The gamble paid off almost immediately; despite having the lowest batting average in the league and no 20-game winner on their pitching staff, the Giants won the Japan Series in Kawakami’s first year on the job.

In addition to the connection with the Dodgers, Kawakami implemented many other practices that have since become standard in the modern game. One example was the introduction of a dedicated closing pitcher; before its introduction, many teams relied on their best starting pitchers to finish games for them, whether through full games as a workhorse or off the bench when not starting.

Kawakami, however, made the closer a feared role in Korakuen Stadium, with the most well-known being the right-handed Yukinori Miyata, better known as “the man of 8:30,” due to his entrance into the game almost always coming around 8:30 P.M. Miyata would win 19 of 20 games in relief in 1965.

Kawakami was also seen as revolutionary off the field, especially with his system of hiring. Instead of following the standard of hiring internally, as most teams did, Kawakami regularly brought in experts from other teams – even their former star players.

One example of a famous Giants coach under Kawakami was Hiroshi Arakawa, a star for the Daimai Onions (now Chiba Lotte Marines) who helped develop some of the Giants’ best hitters, including Sadaharu Oh. Arakawa, it’s said, is responsible for Oh’s famous “Flamingo” leg kick, perfected after months of strenuous training. Another example was Shigeru Makino, a defensive wizard with the Chunichi Dragons who Kawakami hired after reading Makino’s analysis articles in the newspapers. Makino was assigned to Vero Beach to watch the full training of the Dodgers, and Kawakami called him his right-hand man, saying “V9 could not have been achieved without Makino.”

While he was revolutionary in more than one way, Kawakami’s managing tenure was also marred in controversy, as he was labeled as “totalitarian” quite frequently and introduced practices that would become infamous. He would restrict press access to team activities – shutting them out during practice – to gain an advantage over his opponents in a tactic called “tetsu no curtain;” somewhat of a pun, referring to both the tetsu, or “iron curtain” the Communist Bloc had implemented, and his own first name, Tetsuharu.

What’s more, Kawakami constantly expanded his role and his authority over his team. He served as head of the scouting department and even enforced nutritional habits on his players, all in the name of teamwork in achieving the team’s ultimate goal: winning the Japan Series. This meant limiting the egos of the star players that emerged – he would require that prolific sluggers Nagashima and Oh lay down a sacrifice bunt if the game situation called for it. Isao Shibata, the Giants’ famed leadoff hitter and speed demon who would go on to total 579 stolen bags during his career, later said he would never steal a base unless told to do so by Kawakami.

There were plenty of criticisms drawn against Kawakami for his authoritarian rule on the diamond, which many fans compared to high school baseball. They argued that it made NPB less interesting. The media was no help in this matter, as Kawakami’s was notoriously icy and closed off to reporters. Even his players took exception to his tactics, with Tatsuo Hirooka – who himself would later be known for his tough-love managing style – publicly criticizing Kawakami in the press.

Kawakami never seemed bothered by his critics, always reciting this mantra to his players: “Let them say what they want to say, and we will answer with results by season’s end.” Answer he did, eloquently, for nine straight years with Japan Series titles and 11 overall – both accomplishments that are unlikely to ever be matched.

He may have been a curmudgeon, control freak, and frightening dugout figure, but he was perhaps one of the most important figures in the history of not just the all-mighty Giants but also Japanese professional baseball in general. There will never be another “God of Hitting” who can captivate a nation with his colorful bat and then take over the dugout reins as he did.

Editor’s note: it should be noted that a bulk of this information was attained by the piece’s original primary author, Daisuke Chihara, in his first piece for JapanBall. We thank him for his patronage and tireless effort in bringing this piece of Japanese baseball history to an English-speaking audience.