It’s no doubt that baseball has a permanent place in culture; whether it’s your boss telling you that you knocked a presentation “out of the park” or seeing it in countless movies, images and lingo from the game seem to ooze through everyday life. As a result, when everyday life is altered, baseball can be used as a sign of the times; whether it’s the New York Mets wearing New York Fire Department hats after 9/11, or umpires and managers wearing masks during the COVID-19 pandemic.

From 1940 to 1945, baseball was plagued by one of the biggest international conflicts in history: World War Two. Japan and the United States were forever historically linked in this conflict when Japan, who looked to gain power in the world through the Pacific Ocean, attacked the United States Naval Station Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

In the four-year struggle that followed, the war permeated everything in both countries: their culture, their everyday life, and their legacy for years to come. As a result, the war’s effect on baseball was clearly seen; over 500 Major League Baseball (“MLB”) players served, as well as a large, unknown number of Nippon Professional Baseball (“NPB”), then the Japanese Professional Baseball League (“JPBL”), players. Hall of Famers like Joe DiMaggio of the New York Yankees and Ted Williams Boston Red Sox are well-remembered for this, as both laid down their bats to fight for the States: Williams with the Marines, and DiMaggio with the Air Force.

But, unlike thousands of young men who also served, DiMaggio and Williams came back. Over 400,000 American and 550,000 Japanese men died in service of their country, including two MLB players and 69 JPBL players. Their names are enshrined in Hall of Fames and plaques in their respective countries, but a name alone does not tell a story.

What follows are four stories; two American and two Japanese, about the players who made the ultimate sacrifice for their countries; stories of baseball, battles and bereavement. We’ll begin with the Japanese stories, and the Americans’ story can be found here.

Their names were Elmer Gedeon, Shinichi Ishimaru, Harry O’Neill and Eiji Sawamura.

These are their stories.

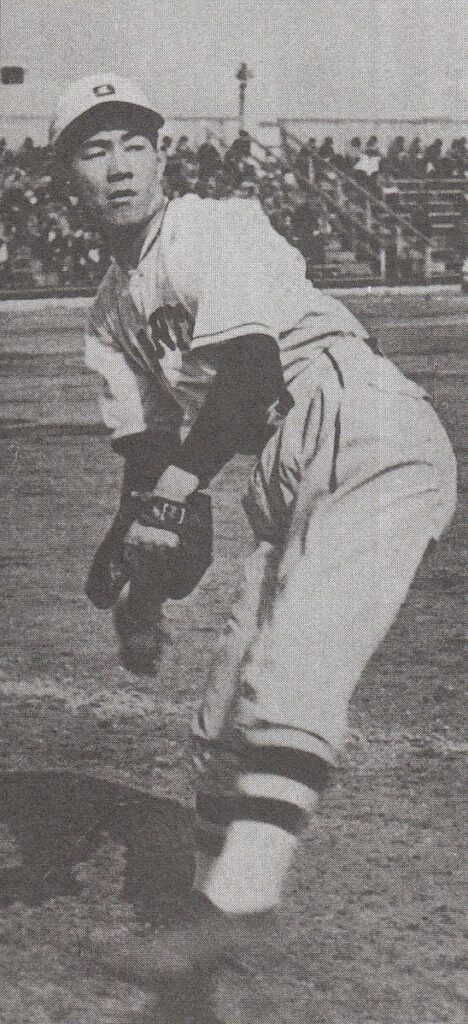

Shinichi Ishimaru: Nagoya Baseball Club, Japan Navy

For our first story, we discuss a player who lived up to his full potential, and lost it all too soon. His name was Shinichi Ishimaru, and before his enlistment in the Japanese Navy, he posted some of the greatest seasons in JPBL history.

Born in Saga City on July 24, 1922, Ishimaru was the fifth son of his father Kinko, a barber. In order to get an education for his sons, Kinko went into severe debt and saw himself in dangerous positions due to stock failures. Shinichi’s older brother, Fujiyoshi, first joined professional baseball to pay off the debt to repay his father, playing for the Nagoya Baseball Club from 1937 on.

Shinichi learned about baseball from Fujiyoshi, an infielder and decent all-around prospect. He became a star pitcher for Saga Commercial High School, earning the reputation as a “one-man team.” Although he had fantastic success as the team’s pitching ace, he still suffered from immense overuse fatigue, and lost in 1939 and 1940 in the qualifying Saga Tournament, failing to make the esteemed Summer Koshien Tournament both years.

As the war picked up in 1940, Fujiyoshi left Nagoya to join the Japanese Army, which was invading China to gain more territory and power in the Pacific. Shinichi, continuing to follow in his brother’s footsteps, joined the Nagoya Club as a replacement for his brother, and began his major league career in 1941. He served as an infielder in his brother’s place, and saw decent time with the club. He knew, however, that once Fujiyoshi rejoined the club he would be out of the position, so he began retraining his arm as a pitcher.

He would be glad that he did, as Fujiyoshi returned in 1942, pushing Fujiyoshi to the pitching staff. Despite playing on a weak team, he was an effective pitcher from the get-go; in his first game, he held the opposition to only two hits, and later won a game against the Yomiuri Giants and their famous gaijin (foreign) pitcher, Victor Starffin. He tallied 17 wins against 19 losses in 1942, but posted a sparkling 1.71 ERA. Moreover, of 105 games played by Nagoya, the team only won 38 games, meaning Ishimaru won a whopping 44% of his team’s games.

It was only the beginning. In 1943, he posted one of the best seasons in the JPBL’s young history, winning 20 games and posting an almost unbelievable 1.16 ERA. Against Yomato on October 12, he tossed a no-hitter, and his final win came on November 6. He was already becoming one of the best players in the game, and he was only 21 years old.

There was a catch, however. In order to avoid the wartime draft, Nagoya enrolled him in night law classes at Nihon University, in order to claim that he was a student and to keep him out of the draft. The university, however, became involved with military delegations in 1944, and Ishimaru became involved with the group; he enlisted with the Japanese Navy in February 1944 to become a student pilot. It’s said that a main reason he joined the Navy was because they did not outright ban baseball altogether.

Going through flight training, he was often faced with sanctions from his superiors. To make up for his behavior, he frequently played for the student reserve team as a pitcher. One story is told where he pitched hard enough to let his team build up a 20-to-30 run lead, all while the opposing team begged for him to pitch softer; his outfielders were apparently seen smoking cigarettes while he worked.

He reached the rank of ensign in December of 1944, but the war was not going as planned for the Japanese, as the United States continued to push and fight back through the Pacific Theater. Noticing this, Ishimaru decided to sacrifice everything for his country and become part of the most dangerous division of the war; he volunteered to become a kamikaze pilot.

Why make this choice? Beyond pride and honor for his country, Ishimaru might have done it out of fear and to protect his family. Mordecai Sheftall wrote that all the Japanese newspapers kept saying that if the Americans won, it would be a nightmare in Japan, of slavery and horrible treatment of the people. It’s not unlikely that Ishimaru, motivated by his father’s sacrifice to educate him and give him a better life, would have wanted to keep his family and country safe.

“I’m very happy to have chosen baseball as my profession,” Ishimaru wrote in a final letter. “There have been many hardships, but also great joy. I’m twenty-four and I have nothing to regret. I’m finishing my career as a ballplayer and it is my destiny to die as a navy officer. My like will end with the word of chuko,” a word meaning loyalty to the emperor and family.

Before boarding his special plane for his fateful mission to Okinawa on May 11, Ishimaru played one more game of catch with a former Koshien tournament star, Koichi Honda. After throwing ten balls, he gave his friend his glove, ball, and a headband with a singular word: “courage.” He then ran to the cockpit, calling out joyfully to members of the press, and took off for his one-way mission.

He was shot down by U.S. forces upon his approach.

Shinichi Ishimaru is one of the most fascinating stories in Japanese baseball history, as he not only realized his unbelievable potential, he set it aside to help protect and honor his country, making the ultimate sacrifice. He’s remembered with plaques and memorials across the country, and his story has been told well as an example of devotion.

For him, it was always about family, and he served them well.

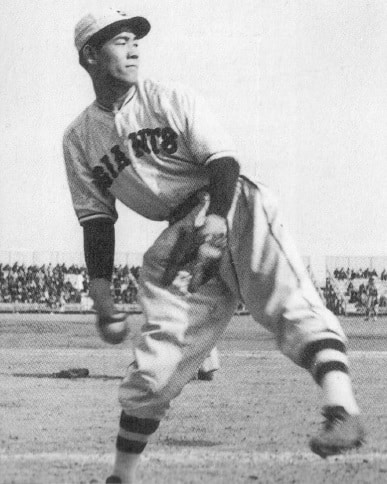

Eiji Sawamura: Tokyo Giants, Imperial Japanese Army

This tale is of one of the most legendary figures in Japanese baseball history who not only showed dominance on the mound, but also served as a symbol of Japanese pride both on and off the field.

Eiji Sawamura was born on February 1, 1917 in Ujiyamada (now Ise City). He was introduced to baseball by his father in elementary school, and quickly became one of the hottest high school players in the country, showing complete dominance on the mound for Kyoto Shogo High School; in one game, he tossed 23 strikeouts. Although his skill was great, his team never went far in tournaments, and his skills often went unfulfilled.

His insane talent, however, did not go unnoticed. In 1934, a group of legendary American baseball players headlined by Babe Ruth, were coming to tour Japan to promote tidings of friendship between the two countries… as well as showing off the massive power the Americans had and perhaps help dispel the anti-American sentiment building in the area. In order to do that, however, Japan would need to field a team for the Americans to play against.

This responsibility fell to Tadao Ichioka, head of the Yomiuri Shinbum newspaper’s sports department. He approached Sawamura with an offer of 120 yen ($36) a month to play with the team, a decent salary for a few months of ball. Unfortunately, if Sawamura joined the team, he would be banned from re-entering high school or university, as rules at the time forbade amateurs from playing official games with professionals. Sawamura, under pressure to make money for his family, agreed.

He appeared in five games for the Japanese, surrendering a whopping 28 runs over 28 and 2/3 innings (7.85 ERA), but nobody paid those stats any attention because for on one glorious day at Kusanagi Stadium in Shizuoka prefecture, Sawamura almost beat the Americans. On November 20, he came in as a relief pitcher in the fourth inning in a scoreless tie, and began to deal. He struck out Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx and Charlie Gehringer in succession, and continued to thrive until surrendering a single home run to Gehrig in the seventh for a 1-0 loss. No Japanese fan cared, however. Sawamura had stood tall against, and at times even overwhelmed, the American murderer’s row. Japan was not a laughingstock.

Following the tour, the Japanese All-Star team stuck together and became the “The Great Japan Tokyo Baseball Club,” operated under Yomiuri mogul Matsutaro Shoroki. The team would play independently for a year, and join the Japanese Professional Baseball League after its formation in 1936; they would rename themselves to the Kyojin, or the “Giants.”

Performing in the league’s infancy, Sawamura quickly became one of the league’s best pitchers, along with his teammate Victor Starffin. In the league’s very first season in 1936, he would post a 14-3 record, a 1.18 ERA, and toss the league’s very first no-hitter on September 25; the Giants would also win the first league championship. He would then win 33 games in 1937, toss another no-hitter on May 1, and win the spring MVP and the league championship as well.

At the same time, however, Japan was beginning to ramp up operations for military practice and officially declared war on China in Summer of 1937. Sawamura was drafted in January of 1938, and trained with the Imperial Japanese Army in Tsu City. He passed with flying colors, and was sent to the front lines of the Sino-Japanese war.

Sawamura fought with the 33rd Regiment of the 16th Division in Shanghai, and his superiors quickly noted his powerful throwing arm. As a result, he was often called upon to toss grenades as far as he could heave them. He took a bullet to the left hand on September 23, 1938, but returned to active service before finally being discharged in October 1939.

After his first tour, he attempted to make a comeback with the Giants, but needed to work on himself first. Excessive grenade throwing had damaged his right shoulder to the point where he needed to refine his throwing motion; he invented a side-arm motion to help him compensate. In his first season back with the Giants in 1940, he made 12 starts and reached a 7-1 record and a 2.61 ERA. He also notched his third no-hitter on July 6 against Nagoya Club, leaving him tied for the most major league no-hitters in Japanese history.

After an average 1941 campaign, he received a second draft notice from the 33rd Regiment, and fought in the Philippines, on an island known as Mindinao. He returned once more in 1943 and tried to rejoin the Giants, but he had completely lost his form; he only appeared in four games, posting a 10.64 ERA and a 0-3 record. The Giants didn’t renew his contract, and, rather than play for anyone else, he retired a Giant at only 27 years old.

As the war grew worse in 1944, however, he was drafted a third time and reported for service. He climbed on a ship headed back to defend the Philippines, and never reached his destination; the ship was torpedoed by the USS Sea Devil submarine, and sunk in the Taiwan Straits.

Sawamura became a legendary image of Japan following his death, in both baseball and in service. In baseball, the annual Eiji Sawamura Award, given to the best pitcher in the NPB every year, is named for him, and he was a member of the first class inducted into the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame. His number 14 was also the first to ever be retired by the Giants, and his three no-hitters are still a career record yet to be broken.

Sawamura was a Japanese icon and a pioneer of the professional leagues in the country, with a life and career cut too short in military service. He served his country in both baseball and service, with his arm piercing past the bats of legendary sluggers and enemy soldiers in military campaigns. Without his performances, Japan would not have been as successful in either baseball nor war, and he gave it all for his home team.

Not bad for a high-school dropout.

Author’s note: This is a two-part story. To read the American stories, check out part two on our baseball blog. To read more about baseball in World War Two, I highly recommend Gary Bedingfield’s “Baseball in Wartime” and “Baseball’s Greatest Sacrifice.“