This is part two of a four-profile story, detailing the two Major League Baseball players who were killed in World War Two. To read two famous stories of sacrifice from the Japanese Professional Baseball League, check out part one here.

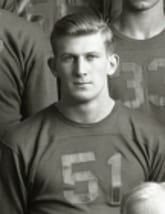

Elmer Gedeon: Washington Senators, US Army

This ballplayer was a true All-American, in all senses of the term. He was strong, fast, and a leader through and through; when it counted, he wasn’t afraid to make the sacrifice.

Elmer Gedeon was born on April 15, 1917, in Cleveland, Ohio, born from a line of athletes. His uncle, Joe Gedeon, was a second baseman for the St. Louis Browns, but was later implicated and banned for life following the 1919 “Black Sox” scandal, as he was present at the conspirators’ meeting.

Elmer grew up in Cleveland and was well-liked by many for his athletic abilities, but more so for his kind heart and actions, according to his first cousin, Robert G. “Bob” Gedeon; Bob remembers a key example when, while ice skating, he fell through the ice, and Elmer fell on his stomach and pulled his cousin back to the surface. Some things aren’t taught, they’re experienced.

Growing to 6 feet 4 inches, Gedeon quickly became known for his athletic exploits, in football, baseball and track. After graduating from Cleveland’s West High School in 1935, he attended the University of Michigan, where he was a star in all three sports; he lettered three times in football, and batted a solid .320 average in his senior year for the baseball team. He’s now a member of the University of Michigan Ring of Honor.

Track, however, is an interesting side note; Gedeon was one of the best track stars in the country at the time, setting American records in the 70- and 75-meter high hurdles and capturing Big Ten titles in 1938 and ‘39. Although he could have easily qualified for the 1940 Olympics (which were originally to be held in Tokyo, and later canceled due to the war), Gedeon instead chose to stick with his love of baseball, and signed with the Washington Senators in 1939.

Upon entering the system, Senators’ manager Bucky Harris suggested that he could use his speed productively in the outfield, and sent him down to the Orlando Senators of the Florida State League to aid his transition from first base. After hitting for a .253 average in 67 games with the club, he was called up in late September and saw action in five major league games, one as a starter in center field. He recorded five hits in fifteen plate appearances, and notched a single RBI. The organization noted his efforts, with team president Clark Griffith even mentioning that he considered him a “fine prospect for a regular job with our club.” The kid had a future.

Then, eleven months before the attack on Pearl Harbor, Gedeon was drafted into military service and inducted at Fort Thomas in Kentucky. After attending training in Kansas, he was transferred into the Army Air Force and achieved his pilot’s wings before joining a twin-engine bomber training program in 1942, rising to second lieutenant.

Still in training, he was almost killed in a training exercise in Raleigh on August 9, 1942, as he served as navigator on a doomed bomber. The plane had serious trouble taking off, as it failed to reach a proper altitude and brushed trees on its attempt to rise; it then dove into a nearby swamp and burst into flames. Gedeon, although suffering from three broken ribs, freed himself from the wreckage. He noticed, however, that crewmate Corporal John Rarrat was still inside, and crawled back into the burning wreckage to rescue him. He succeeded, although suffering from severe burns and grafts in addition to the ribs.

Although Rarrat later succumbed to his injuries, Gedeon’s heroic decision did not go unnoticed: he was promoted to first lieutenant and received the Soldier’s Medal for his efforts. Moreover, however, he considered the accident to be an excess of bad luck, as he wrote to Bob that now that he had his accident, “it [was going] to be good flying from now on.” He also wrote that he would be back in baseball following the war.

Following his recovery, Gedeon was assigned to the 394th Bomb Group, and was shipped overseas to Boreham Field in England with the group in the fall of 1943. The group’s purpose was known as “bridge busting,” to ramp up attacks in advance of the allied invasion. Gedeon served as the group’s operations officer, spending most of his days out of the cockpit and behind a desk. He was in charge of organizing missions, interpreting higher decisions and assigning crews and planes.

On April 20, 1944, Gedeon, along with around 30 B-26 bombers, piloted a mission to Esquerdes, France. Their target? A Nazi launch site for V-1 rockets, which were used in attacks against England in the Nazi’s attempts to invade. As part of Operation Crossbow, the attack would help cripple German weapons and gain an advantage.

Gedeon’s plane dropped its bombs, but missed and became caught in anti-aircraft fire. His plane was directly hit from under the cockpit, and the plane went up in flames. His co-pilot James Taaffe watched as the plane dove and Gedeon slumped over the cockpit, then crawled to safety through the escape hatch. He watched as the plane tumbled to the ground and exploded upon impact, killing Gedeon and the five other crewmen on board.

Although he was an unbelievable athlete, Gedeon was better known for his selflessness and heroic actions, always putting others’ lives before his own: a true All-American.

His remains are buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

Harry O’Neill: Philadelphia Athletics, U.S. Marines

Our third story comes from one of the most patriotic cities in the States, and tells how a star athlete, known for his prowess and toughness in the most difficult positions, fought and pushed until he met an unforeseeable obstacle.

Harry O’Neill was born in Philadelphia on May 8, 1917, and grew up just outside of the city around Drexel Hill. He attended Darby High School and found success in three sports: baseball, football and basketball; he captained the basketball team to a regional Kiwanis tournament title and was named to the All-Kiwanis team. After graduating in 1934, he spent a bit of time at Malvern Prep School before heading to Gettysburg College.

At Gettysburg, he really began to shine. He played as the kicker for the football team, the starting center on the basketball team, and joined a three-catcher staff for the baseball team. His contributions helped Gettysburg become somewhat of an athletic powerhouse, as he led the basketball team to titles in 1937 and 1938, and helped the football team win the Eastern Pennsylvania Intercollegiate championship in 1938.

What captured everyone’s attention, however, was his skill as a catcher on the baseball team. He was 6-foot-3 and 205 pounds – particularly imposing for his time – and had such pure athletic ability that his presence behind the plate was a huge asset for the team. In his role as a catcher, he helped guide the team to an 11-4 record and the 1938 Eastern Pennsylvania title. He even saw some clutch moments at the plate, knocking in a key run in a tough 5-4 win over rival Penn State.

After graduating in 1939 with a degree in history, he was seen as a great asset for any MLB team, and was tied to the up-and-coming Washington Senators. O’Neill, however, was keen on the idea of staying home in Philadelphia and playing for their legendary manager, Connie Mack. He signed a contract right after graduating for $200 a month, and immediately joined the team as a third-string catcher.

O’Neill, however, didn’t see much action, mostly riding the bench while watching his teammates play through a lousy 55-97 campaign. He did make one appearance in a lopsided 16-3 road loss to the Detroit Tigers, appearing up as a defensive replacement in the eighth inning; he did not record a single plate appearance.

Although he didn’t see any more major league action, being close to home had its perks. He split time between the Allentown Wings and Harrisburg Senators of the Interstate League, and, to make money and spend time on the side, he took up a job as a teacher at his alma mater, Upper Darby,

Then the war started.

In September 1942, O’Neill joined the U.S. Marine Corps and began basic training in Quantico, Virginia. He graduated as a second lieutenant, and began more intensive training in California. After moving up to a first lieutenant in January 1944, he was prepared for amphibious assaults in the Pacific Theater, while his wife moved to California to be closer to him; his home came to him for support.

An amphibious assault is defined as a military strategy that uses naval ships to transport men and weapons onto enemy territory, who then launch an assault to capture it. It’s something incredibly difficult and strenuous, and requires strength, courage and mental acuity. Like D-Day from 1944, these kinds of assaults were happening regularly in the Pacific, as the United States pushed to recapture more territory from Japan. Harry O’Neill participated in three of them.

He first participated in the Battle of Kwajalein in February 1944, which was considered a major turning point for the United States in the Pacific; it meant they had penetrated the “outer ring” of territory Japan had set up. He then participated in the Battle of Saipan in June, where a U.S. victory led to the resignation of the Japanese Prime Minister. At Saipan, he took shrapnel to the shoulder and was sent home for several weeks before returning to the front to participate in the Battle of Tinian.

Then, in February and March of 1945, he became part of one of the most notable campaigns in U.S. military history: The Battle of Iwo Jima. Although its strategic importance is now debated (the island would only be used in emergencies following the U.S. victory,), it’s moral significance is undeniable. The five-week-long battle was the bloodiest in the war, as Americans used air power and trekked through the jungle to drive the Japanese out over five weeks. O’Neill was one of those men, taking part in several assaults and pushing through the difficult terrain of the northern section of the island.

On March 6, O’Neill stood in a crater to get cover from shots from the hill above his group, peering over the terrain. Before he could make a next move, a shot from a sniper rang out of nowhere and pierced his throat, severed his spinal cord, and killed him instantly.

It was a month before his wife, Ethel, knew he passed.

O’Neill is a story that’s woven into American folklore; the hometown kid, called up for a single inning of Major League ball, who goes to war to become a hero and is killed in the trench by an unseen, unknown bullet. He, along with Gedeon, is the one of only two MLB players who were killed in the war. Yet his name, along with all the others who meant something to someone, will not be forgotten. As his sister Susanna wrote to Gettysburg,

“We are trying to keep our courage up, as Harry would want us to do. But our hearts are very sad, and as the days go on it seems to be getting worse. Harry was always so full of life that it seems hard to think he is gone. But God knows best, and perhaps someday we will understand why all this sacrifice of so many fine young men.”

Heading Home:

The four baseball players are forever intertwined in their stories of baseball, country pride and sacrifice. Their names shine forever on plaques, reminding people passing by that although it’s a national pastime for both countries, sometimes there are more important teams to play for.

Gedeon. Ishimaru. O’Neill. Sawamura. Four players. Two countries. One game.

Author’s note: Their stories, however, are not the only ones. There are hundreds of stories from baseball in the war from all sides, and has always been a common thread through modern international conflicts. To read more stories, I highly recommend Gary Bedingfield’s “Baseball in Wartime” and “Baseball’s Greatest Sacrifice.” which both helped immensely in the research and writing of this story.

For more baseball history, check out JapanBall’s Articles and Features section!