February 2019

Ask the average Major League Baseball fan what he or she knows about Japanese baseball, and the answer will probably include a mention of “Ichiro” (Suzuki), Yu Darvish, or the Angels talented Shohei Ohtani. For the less-informed, the extent of their familiarity might only consist of the Tom Selleck movie, “Mr. Baseball.”

In September 2018 I made a baseball-themed visit to Japan. I thought a few observations about how different Japanese baseball is might be of interest to those not familiar with it.

Rather than concentrating on individual players, teams or quality of play, which followers of Japanese baseball would already be familiar, I will present a review of the distinct differences between the style of American and Japanese baseball for the average fan who has not experienced it, with a brief background of how the game was established and grew in Japan.

These observations are mainly based on my visiting regular-season Japanese (Nippon) Professional Baseball games at five different parks, in Tokyo, Yokohama, Nagoya, Sendai and Seibu-Tokorozawa (outside Tokyo). The recent Japan All-Star series was played at two of the stadiums we visited, the Tokyo Dome and the Nagoya Dome, and also at Hiroshima. Our group included members of SABR and the MLB Supervisor of the Arizona Fall League. Though this was my 12th trip to Japan, it was the first time I had attended games there.

Visits by U.S. Major League teams bring to mind the famous 1934 visit that included Babe Ruth and other all-stars, along with Moe Berg (whose outside activities on that visit have been well-documented), the Yankees in 1955, the Dodgers in 1956, and the more recent visits by Major League All-Stars.

U.S. teams have made more than 40 visits to Japan dating back to 1908, with early visits including teams led by Charles Comiskey, John McGraw and Casey Stengel, and hitting instruction by Ty Cobb. Post-war, different Major League teams would make nearly annual visits, but now teams consist of major leaguers drawn from numerous organizations.

The Oakland A’s and the Seattle Mariners, open the 2019 Major League Baseball season early in the Tokyo Dome in March.

Professional baseball in Japan dates back to 1936, though it is generally considered that the game was first introduced to the nation in 1872 by an American teacher in Japan, Horace Wilson, in what would later become Tokyo University, and who is recognized in their Baseball Hall of Fame in Tokyo. Though sometimes called “beisu boru,” the formal name, adopted in 1894, is “yakyu,” a translation of “field ball.”

A strong case can be made that the father of “modern” organized baseball in Japan is America’s Lefty O’Doul. After an initial all-star team visit in 1931, he was instrumental in the formal development of the sport there and made at least 20 visits to Japan during the 1930s and 1940s. He was particularly helpful in the establishment of the Tokyo team, the first and longest-extant team in Japanese professional baseball.

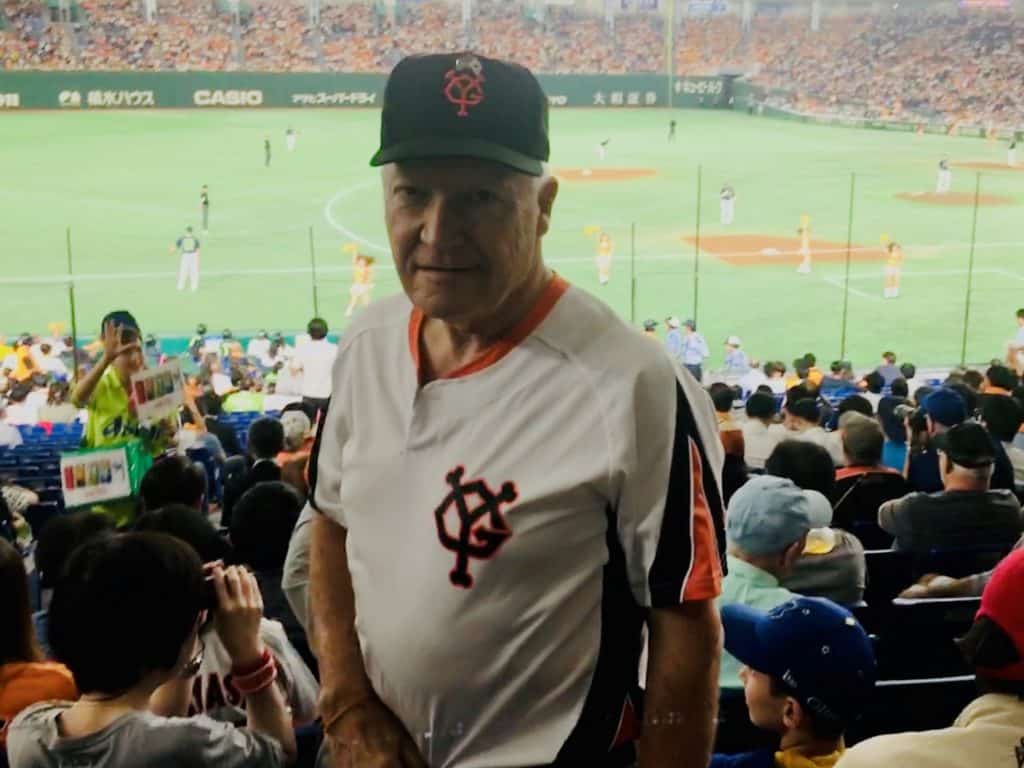

O’Doul gave the team its first name, the “Tokyo Giants,” after his final Major League team, the New York Giants. To this day, their team colors are orange and black, and their caps bear an interlocking “YG” (for Yomiuri Giants) in orange and black. After the war, he returned to Japan to help re-establish the game. At one time he was considered the most famous American baseball figure there aside from Babe Ruth.

Since 1950, there have been two professional leagues, the Central League and the Pacific League, with a total of 12 teams and 727 players last season. The Central League has long been considered the more powerful league with stronger teams and higher attendance. The Nippon Professional Baseball Leagues play a 143-game schedule during virtually the same period as Major League Baseball.

This last season, 2018, there were 29 U.S.-born players in the JPL, or “gaijin” variously translated as “foreigner” or “outsider.” There was also one foreign manager, Alex Ramirez of the Yokohama DeNA Baystars team in the Central League, who played with the Indians and Pirates, 1998-2000. Among some of these foreign players were Mike Bolsinger, David Huff, Randy Messenger and Dennis Sarfate, a real star in Japanese baseball, and the highest paid foreign-born player.

Also, the senior advisor for many years for the Tohoku Rakuten Golden Eagles (Pacific League) team at Sendai (a city in northern Japan) for many years, is Marty Kuehnert, former president and part owner of the Birmingham Barons, who has spent 45 years in Japanese baseball. He gave our group a private interview session at the ballpark before the game there, as he is a long-time friend of our tour director, Bob Bavasi, who is the son of Buzzie Bavasi, a Hall of Fame-nominated baseball executive.

Many American-born major leaguers, with instantly recognizable names, have played professionally in Japan since the war, with varying degrees of success, effort, and adaptation. Just a few include Randy Bass, Don Blasingame, Alex Cabrera, Larry Doby, Cecil Fielder, Paul Foytack, former Washington Nationals manager Davey Johnson, Don Newcombe, Ben Oglivie, Zoilo Versalles, and Bobby Valentine, who managed a local Japanese team.

When former Major League players began playing in Japan in more significant numbers, the diversity between the two approaches to the game became apparent and well-publicized. American players were confronted with a universally-intense training system they were unfamiliar with and considered highly regimented. Comparisons were made with football or military training camps. To be sure, U.S. spring training and individual off-season training, if any, was minimal at that time, unlike today.

Correspondingly, Japanese players considered American players lazy and not as committed. To a certain extent, this was true of some well-known American players who were interested in other pursuits more than dedication to baseball and put forth little effort. In retrospect, this was not entirely surprising. A large proportion of players were older and at the end of their Major League careers. They were there to earn a few more paychecks before calling it quits.

The situation is considerably different today. In the United States, American professional players employ a regimen as demanding as many of those in Japan, and those playing in Japan today are generally younger and at an earlier stage in their careers. Of the 29 U.S.-born players this past season, the average (mean) age was 30.5 years, with the age range between 26 and 37. Their prior Major League experience level is anywhere from zero or one year to eight years.

Hundreds of foreign-born players are on Japanese teams every year, largely from Caribbean nations and Korea. Some Nippon Professional Baseball teams have had working agreements or even owned outright a Minor League team.

On the other side, at least 60 native Japanese-born players have appeared in the Major Leagues (not including at least six U.S. citizens born in Japan), 17 of which were on 2018 MLB rosters. The first Japanese-born player in the Major Leagues was Masanori Murakami, who played for the San Francisco Giants during the 1964-1965 seasons, and was very popular with the local Japanese community in the Bay area.

A national draft system was established in 1966, and in 1998 a U.S.-Japan agreement established a procedure for Major League teams to negotiate bids for players on their professional teams.

Hideo Nomo became the first player to go directly from Japanese pro ball to the Major Leagues, signing with the Dodgers in 1995. Ichiro, as he goes by his first name, was the first Japanese position player to play in the majors (by one day), in 2001.

Japan’s currently most-popular native-born player in the Major Leagues, the Angels’ Shohei Ohtani, receives blanket coverage on Japanese television. His almost every at-bat is shown, usually on a delayed basis because of the 9 to 12-hour time difference. This is not without precedent. Former Dodger and Mets pitcher Hideo Nomo received similar television coverage in Japan every time he started a game. Major League World Series and All-Star games have considerable live coverage by the Japanese press and television, with an army of their photographers, writers, and reporters at those games.

Salaries in the NPB are, not surprisingly, considerably less than in Major Leagues. Also, their schedule is 19 games shorter. The highest-paid player made just under $5,000,000 in U.S. dollars this year, at the current exchange rate. The next 14 players made three million U.S. dollars or more. The highest-paid U.S.-born former Major Leaguer is the aforementioned Dennis Sarfate, formerly of the Brewers, Astros, and Orioles. He earned just over four-and-a-half million U.S. dollars, the fourth-highest salary in the NPB. In 2018, the average salary for all players was approximately US $338,000, well below the 2018 minimum MLB salary of $545,000. Before major league salaries took off in recent decades, the total payroll of the Yomiuri Giants of Tokyo exceeded that of seven U.S. Major League teams.

Japanese stadiums are, in general, similar to those in the U.S. (but not Cuba or some other Caribbean-area countries). Some of the parks in smaller cities are more like AAA parks in the U.S.

Domed stadiums are popular in Japanese professional ball. Six of the stadiums are domed, the first being the Tokyo Dome, seating 45,600 for baseball (second largest in Japan), that opened in 1988. It was initially called “The Big Egg,” for the appearance of the white fabric dome that remains inflated through pressurization-induced air. Much attention was paid to the Washington Nationals’ Juan Soto hitting the roof of the Tokyo Dome on the fly during the Japan-MLB All-Sar series. The highest point on the inside of the dome is 184 ft. 4 in.

Five of the domed stadiums were originally constructed with domes. However, the Met Life Dome, used by the Saitama Seibu Lions at Tokorozawa, originally opened in 1979 as the Seibu Lions Stadium, had a dome constructed over it in 1997-1998. Unlike other domed stadiums, the bottom of the dome was separately-elevated over the stands, uniquely allowing home runs to be hit outside of a domed stadium. There is no back wall, ostensibly to allow fresh air into the stadium as it could not be air-conditioned. However, in the hot, humid summer air of the Tokyo region, many in our group failed to detect any fresh air, and it was quite warm and humid inside with no breeze.

Their stadiums are scrupulously clean. You do not see trash lying around the stands and fans do not throw trash on the ground. They carry plastic bags and put all their refuse in them, depositing the bags in trash cans when leaving. When concessions are purchased, they come in a plastic bag to put the trash in. Though outside food and non-alcoholic drinks are generally allowed to be brought in, they may not be carried in their original containers in many stadiums. Free paper or plastic cups are handed out at the gates for fans to pour their drinks into. As you depart some of the stadiums after the game, the employees at the exits politely bow and thank you for attending. Not surprisingly, I did not see parking lots at any stadium. Parking lots anywhere in large Japanese cities are very scarce as space is at a premium and land is too valuable for anything but buildings.

As befitting a technological country like Japan, their scoreboards are as modern as any in MLB, with all the bells and whistles and latest stats, though not as large. If there were any exploding scoreboards, I didn’t see them. They even show pitch speeds, in kilometers per hour. Most scoreboards list players names, lineups, and statistics in both Japanese and English, but some only post it in Japanese, which makes it difficult to keep a scorecard.

I don’t recall seeing any locals keeping score, and none of the games I attended were scorecards or score sheets made available, free or for sale. The Yomiuri Giants at the Tokyo Dome, however, gave out a booklet like those given out at U.S. minor league parks, with all pertinent team and stadium information, updated periodically. Though the cover is in English, the contents are entirely in Japanese. Unlike the recent All-Star series there, PA announcements are only in Japanese. Commercials are run on the scoreboard between innings.

They do show instant replays on their scoreboards, but I don’t believe they have challenges or mound-visit limits, as far as I could determine. In all the games I attended, I never once saw a player or manager contest or argue a call with an umpire, or for that matter, any display of anger or temper by a player. I would imagine if a batter charged the mound or the benches cleared, they would first respectfully bow to each other, as before the start of a martial arts match. It is much like a throwback to American baseball in the 1950s, except for the domes, electronic scoreboards, and the DH. I didn’t see any “high fives,” bat flips or backward caps in the dugout. No long beards on the native players or extensive tattoos or piercings. And no constant stepping out of the batter’s box to re-adjust batting gloves.

Extra-inning games do not go beyond 12 innings. If it is still tied after 12 innings, the game ends in a tie, at least during the regular season. Some teams had five tie games during the 2018 season. Although purists may disapprove of this arbitrary limit, fans do have some idea of when they will be able to leave, especially in bad weather or late at night.

Interestingly, every team has its nickname, e.g., Giants, Lions, Dragons, etc., emblazoned in English on the front of their jerseys, and not in Japanese. Also, their stadiums have the stadium names in English, along with Japanese, in some cases. However, inside the stadiums, including the concession stands, very little is written in English. Edible concessions consist mainly of various rice bowls, sushi, and chopsticks, with some Japanese versions of hamburgers and hot dogs, and some sweets such as very expensive ice cream cups ($4.00 US equivalent for a 3.6 oz. mini-cup). Beverages generally are sodas, beer, water, and some fruit juices.

Unlike in the U.S. and other countries, I saw very little wearing of team colors, caps, jerseys, or team-related items outside of the stadium area, especially on city streets and public places. At the Tokyo Dome, numerous fans sported Yomiuri Giants jerseys and caps in various styles and colors, with either their “YG” logo or “Giants” (in English) on the front of their jerseys. Some team paraphernalia is sold in stores in and around this stadium and those in many other cities. Some have elaborate and well-stocked team stores, as good as any in the U.S. and there are almost as many signs for merchandise in English as in Japanese.

One aspect of local customs that will be of interest to first-time travelers to Japan, particularly those from North America and Europe, is the near-total absence of tipping, anywhere, for the average tourist engaged is customary tourist travel. Tipping is not customary in Japan. Not for lodging, not at restaurants, not for taxi drivers, maids, porters, not for anything. Initially, it takes some adjustment to overcome the practice of automatically leaving tips. Also, in almost all instances, listed prices everywhere include all taxes and do not come as an added, unlisted charge.

Their dugouts are unlike those in the U.S. or anywhere else. Rather than a bench, many have comfortable individual leather chairs. In one stadium, I believe it was the Tokyo Dome, each player, regardless of his status, had a large, luxurious well-padded lounge chair, the kind you see in many Major League home clubhouses and modern, upscale U.S. theaters, arranged in rows. Who would want to leave the dugout to go on the field?

One feature that impressed many foreign visitors, including the TV broadcast crew during the recent All-Star series, is the fan enthusiasm, involvement and noise level during games. What you saw on television is nothing compared to what it is like in person for a regular-season league game. The cheering is non-stop during play, from start to finish of the game, with the only breaks between the innings while the competing cheering sections set up for their half-inning.

The cheering is not random. They are well-choreographed groups of hundreds with band instruments, singing and chanting prepared rhythmic pieces in unison. During the All-Star series, this only occurred when the Japanese team was at bat, but during regular-season league play, both teams have their cheering section in separate sections of the bleachers, so the action never stops.

It is much like some college football games in the U.S. or some of the recent World Baseball Classic games, especially in Miami. Additionally, cheerleaders for both teams perform in colorful uniforms at various times during the game on the sidelines or on the field, along with several furry mascots.

However, the noise level is still not as high as at some ballparks in Cuba, with their blaring horns, and continuous bongo drumming (up to 30-minutes, non-stop, even between innings), and random shouts, often at a level that is painful to the ears.

Fan participation is not limited to bands and organized cheering. Many teams have unique methods of showing support. One team’s fans unfurl and wave colorful parasols at designated times. At some stadiums, balloons are sold just before the seventh inning, in time for fans to inflate them to their full two-foot length, and on cue during the seventh inning stretch, they are released. It’s a colorful sight at a night game as thousands of colorful balloons rocket skyward, illuminated by the stadium lights. It does create a brief delay while the ground crew clears the expended balloons from the field and the screen behind home plate.

At some parks, when a foul ball heads to the stands, the instant it leaves the bat a siren goes off in the affected area of seating to alert fans who may not be paying attention, as in some parks netting does not extend as far as it does in U.S. parks.

One noteworthy, if not amusing, characteristic of the fan experience, is the presence of the beer vendor girls at almost all parks. During the entire game, dozens of young (none older than their 20s), cheerful and highly energetic girls continually run, not walk, up and down the seating aisles in the grandstands, at least 100 feet each way, selling beer, without any apparent exhaustion.

Each beer girl carries a large container on her back in the shape of a beer keg for the particular brand they are selling, with a hose attached. They dispense the beer from that container into plastic glasses. They continue this pace for over two hours and I never once saw one without a smile on her face the entire time.

They did not play “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” during the 7th Inning of any game I attended, however at one stadium they played it before the start of the game, and at Sendai, the song was played repeatedly on a continuous-loop tape at the front entrance of the stadium as fans were coming in. In both instances it was in English, in a U.S. commercial recording from the 1940s or 50s. They played the Japanese national anthem, “Kimi Ga Yo” (“His Majesty’s Reign,” one of the shortest national anthems in the world) before only two games I attended. At the game in the Tokyo Dome, U.S. NBA star point guard for the Golden State Warriors, Steph Curry, on a promotional tour of Japan, threw out the first ball. He is well known and popular in Japan.

The Tokyo Dome, the centerpiece of the Japanese Professional Baseball League, is the home of the Yomiuri Giants (as well as numerous other sports and entertainment events, year-round), a team universally-regarded as the New York Yankees of Japanese ball, dating back to 1934 – two years before the NPB league was formed – and the winner of 45 baseball titles. The team was created by the president of the Tokyo Shimbun (“Tokyo Newspaper”), still in print today, and originally staffed with many of their all-stars who played the visiting Americans in 1934.

Originally called the “Dai Nippon Tokyo Yakyu (‘baseball’) Club, they were renamed the “Yomiuri Giants” in 1947. As mentioned, the name was informally coined by Lefty O’Doul of the New York Giants, during his visit there on the 1934 American All-Star Tour, his last year in the majors.

The entire immediate area of the stadium is known as “Tokyo Dome City,” with a major hotel, amusement park, live entertainment, numerous stores and restaurants, and the official Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame, inside the stadium, itself.

As one might expect in Japan, there is a state-of-the-art commercial indoor batting range in a building next to the stadium. Unlike a mechanical arm slinging a baseball, there is a life-size video on a screen of a star professional Japanese pitcher pitching in a game, one right-handed, one left-handed, your choice. Where the pitcher’s hand reaches the release point, there is a hole in the screen where a baseball shoots out of it, as close to an actual pitch one can see off the field. As all instructions were in Japanese, I could not determine what pitch options were available, speed, type, number, cost, etc. The pitches appeared to be in 60 mph range. The only downside is they use aluminum bats. Cracked wooden bats can be expensive.

The Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, located in a part of the stadium with a separate entry, has some commonalities with Cooperstown Museum, especially a room full of plaques that look similar to those on display in the U.S. museum. There are currently at least 201 inductees, with approximately 44 still living. One Hall of Famer should be familiar to most Western baseball fans, Sadaharu Oh, inducted in 1994 with 868 home runs. A number of the awardees died in WWII or were so severely injured their careers ended. A total of 69 Japanese professional baseball players died in the war, compared with a total of two former United States major league players.

One of those honored was perhaps their best pitcher ever, Eiji Sawamura, for whom their equivalent of their Cy Young Award is named, the “Sawamura Award,” beginning in 1947. During the 1934 visit of the American All-Star team, he performed a Carl Hubbell-type exhibition, when as a 17-year-old high school student, he struck out nine MLB all-stars, including Charlie Gehringer, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and Jimmy Foxx in succession. It may have been a more remarkable accomplishment as Carl Hubbell was an established major league star when he performed his feat.

The American manager, Connie Mack, was so impressed it has been reported that he was interested in signing him. Though the American players were greeted with great enthusiasm, anti-American sentiment was growing in Japan by that time and Sawamura is reported as saying, “My problem is, I hate America and I can’t make myself like Americans.” Nevertheless, he visited the United States on a promotional tour the following year, 1935 and was warmly received. It is said that while signing autographs, he was tricked into signing a contract for the Pittsburgh Pirates, but there is some dispute about the validity of this claim.

Sawamura went on to a stellar professional career with three no-hitters, during 1936-1937 and 1940-1943, despite being called into service three times, beginning in 1938. He incurred a shoulder injury while serving which impacted his performance.

In 1943, he enlisted in the Japanese Imperial Army and was died in December 1944 at age 27, when the transport ship he was on was torpedoed by a U.S. Navy submarine in the Pacific off the coast of Formosa (Taiwan.) A good, in-depth presentation of his career, the 1934 tour, and related events can be found in the 2012 book, “Banzai Babe Ruth.”

American baseball’s history and influence are well-represented in the museum with many U.S. baseball artifacts, uniforms, posters advertising various American team visits, and film highlights of some of the notable visits by American All-Star teams. It is well worth a visit, either before a game or independently, and one can see most of the displays in two hours or less.

A factual error in the otherwise excellent Ken Burns baseball history series is the statement that Japan abolished baseball during the war in defiance of the United States. This most assuredly did not happen and probably was a misinterpretation of actual events. Professional baseball in Japan continued until the last months of the war, though some games may have been canceled due to “field conditions,” i.e., “Game called on account of stadium being bombed out.” The chain of events as listed in the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum follows:

“1940: All teams adopt Japanese team names in conformity with wartime pressures.

“1943: All baseball teams are “Japanized.” (Note: Such terms as “safe” and “out” were dropped and changed to other non-specific descriptions.)

“1944: The league is renamed the “Japan Baseball National Service,” but play was discontinued on November 13, 1944.

“1945: Pro baseball resumed with an East-West All-Star game on November 23, 1945.

During the 1940 – 1943 seasons, Japanese professional baseball managed to play a schedule of over 80 games. By 1944, that was reduced to 35 games, playing one game every four days. By August 1944, the season had ended for all practical purposes.

At the beginning of the American occupation in 1945, the Supreme Allied Commander, General Douglas MacArthur, ordered that the then-existing professional stadium in Tokyo, being used as an ammo storage area at the time, be cleared out and restored as a ball field.

Baseball has long been a unifying endeavor to a widely diverse, and often politically hostile peoples and cultures of the world. It has survived world wars, depressions, revolutions, and technological changes, bringing together players, fans and nations in a peaceful manifestation of competition. Notwithstanding, Japanese baseball is a unique and entertaining experience, a world of its own, where that nation’s long and distinct culture has melded with those of other cultures, while retaining the charm and attraction of its own. It is one worth experiencing, despite the distance and expense involved.

Tour Note:

The trip I took for these observations was run by JapanBall Travel. This is a tour company run by Everett, WA-based Bob Bavasi, a son of Buzzie Bavasi (GM of the Brooklyn and LA Dodgers, first President of the San Diego Padres and GM of the California Angels). It is conducted annually, during September, with occasional brief trips at other times. One of these will be this coming March 2019, to see the MLB season-opening series in Tokyo.

Tour members meet in Tokyo for an approximate one-week baseball-themed tour of Tokyo and several other cities on a rotating basis, depending on the game schedules in the Japanese professional leagues. Pre and post-tours are also offered in conjunction with the main tour, mainly to cities not visited on the main tour and lasting a few days each. A native Japanese guide and interpreter accompany all trips.

The trip frequently sells out well in advance. Lodging is in upscale downtown business hotels, often within walking distance of the stadium, rail station, or both. Inter-city travel is by the comfortable, unfailingly punctual Shinkansen (“new trunk line” or “new main line”) trains, more frequently known as the Bullet Train, with reserved seating and at speeds of up to 200 mph.

Not one train ride I took was more than one minute late at any station. This is the norm when no outside factors, such as storms or earthquakes, occur. Stadium seating is good and is generally in the front part of the grandstand in reserved seats. Usually, five or six games are scheduled, day and night, and with so many domed stadiums, rainouts are minimized.

Though the tour is primarily devoted to attending games, there is some free time for independent and guided touring, sightseeing and shopping in Tokyo and other cities. Many participants take the opportunity to witness the quintessential Japanese sports event, a Sumo wrestling match when scheduling allows. Also, attending Kabuki performances and other cultural presentations, and visits to various museums, shrines, and historic sites is an attractive opportunity.